Introduction

The most fundamental rule of property law has always been this: the law protects the peaceful man in possession. But what happens when the very mechanism meant to safeguard that peace an injunction is sought by a person who admits they are not in possession, merely on the strength of a contested title? The Supreme Court recently tackled this question, underscoring a vital principle that should serve as a wake-up call for all property litigants: In property disputes, possession trumps mere paper title if the ownership itself is under a cloud.

The recent judgment in S. Santhana Lakshmi & Ors. v. D. Rajammal1, which arose from a contentious family partition suit, provides the perfect narrative flow to understand this legal tightrope walk. The dispute centered on 1.74 acres of dry land, where the plaintiff, D. Rajammal, sued her brother for an injunction simpliciter—a bare injunction restraining interference and alienation without seeking the more substantive relief of a declaration of title or recovery of possession. The plaintiff’s claim was rooted in a Will executed by her father, and she contended that the defendant brother was a mere tenant. Conversely, the defendant claimed to be a co-owner, asserting full possession and challenging the testator’s right to bequeath the land, claiming it was ancestral property.

The suit’s journey through the lower courts revealed the typical confusion surrounding this issue: the Trial Court and the High Court ultimately decreed the suit in favour of the plaintiff, holding that once the Will was proven, possession naturally followed title, thereby enabling the injunction. This approach, however, fundamentally misconstrued the relationship between title, possession, and equitable relief.

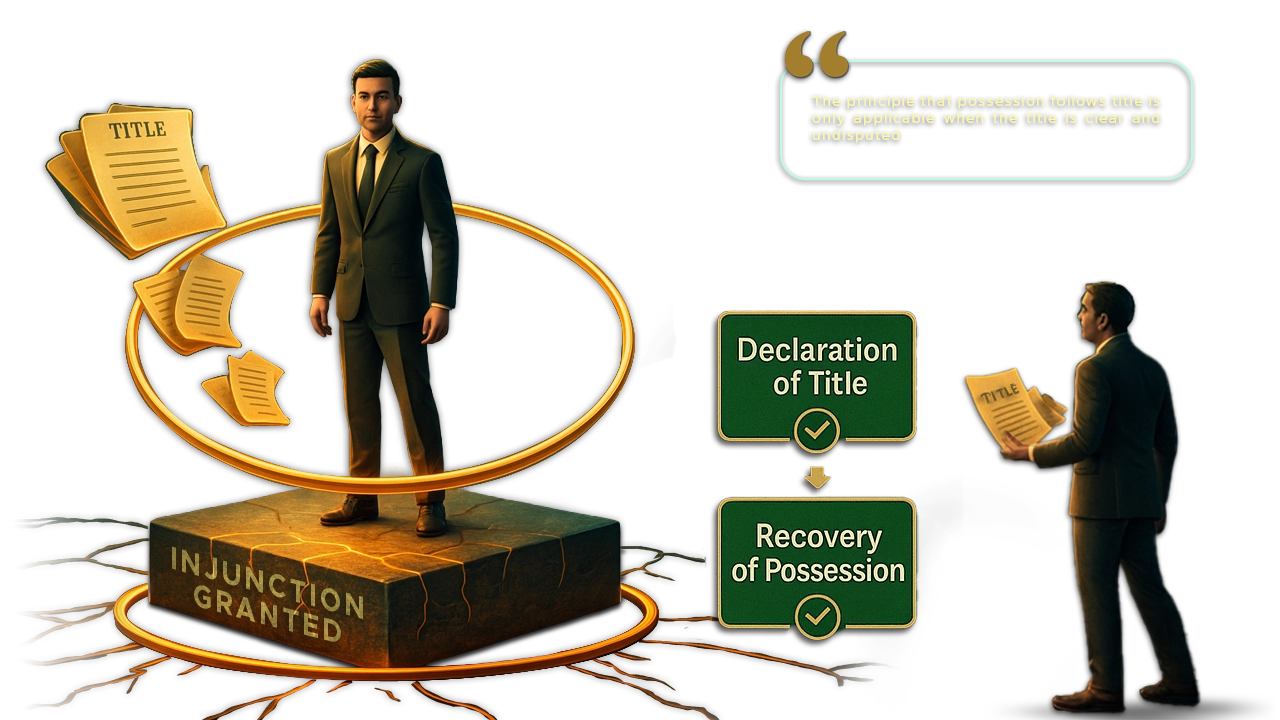

The crux of the matter before the Supreme Court lay in the fact that the plaintiff, in her own pleadings and evidence, had clearly admitted that the defendant was in actual possession of the property. The Court’s rationale was clear and emphatic: an injunction against interference is a protective remedy available only to a party who establishes a prima facie case of actual, peaceful possession. It cannot be used to indirectly establish a title or recover property. The bench held that the injunction restraining interference with peaceful enjoyment was unsustainable, especially because the defendant’s contention that he was a co-owner in possession, having occupied the land and made improvements, threw the title into serious dispute. The principle that “possession follows title” is only applicable when the title is clear and undisputed. When title is contested and the plaintiff is admittedly out of possession, the mandatory course of action is to seek a declaration of title and recovery of possession. By omitting the latter, the suit was rendered incomplete and a bare injunction was rightly denied.

This modern stand is not a new invention but a strict enforcement of the established judicial policy set out in the landmark case of Anathula Sudhakar v. P. Buchi Reddy2 (2008). In Anathula Sudhakar, the Supreme Court had systematically laid down the scenarios where a suit for injunction simpliciter is maintainable, unequivocally stating that where the plaintiff is out of possession and the title is contested, he or she must file a suit for declaration and consequential relief of possession. The S. Santhana Lakshmi judgment applies this established rationale by emphasizing that procedural expediency cannot override substantive law; a plaintiff cannot use the convenient route of an injunction to circumvent the heavier burden of proving and recovering possession when title is clouded.

This principle has been consistently reinforced by the Supreme Court in subsequent rulings:

Rame Gowda (D) by LRs. v. M. Varadappa Naidu (D) by LRs. & Anr. (2003)3: This judgment emphatically deals with the importance of settled possession. The Court held that a person in settled possession cannot be dispossessed by the true owner except by due process of law. While this case supports the possessor’s right against forcible eviction, it reinforces the negative implication: if a person (even a title holder) is not in possession, they cannot get an injunction to restrain interference by the possessor, unless they seek the substantive remedy of possession first. The Court’s protection is for the physical fact of “settled possession,” which must be disturbed only through law.

T.V. Ramakrishna Reddy v. M. Mallappa (2021)4: The Supreme Court reiterated the Anathula Sudhakar principles. In this case, the court found that since the plaintiff’s title was not only disputed but was also under a cloud raised by the defendant’s claims of possession and title through other documents, a suit for bare injunction was not maintainable. The plaintiff ought to have sought a declaration of title and recovery of possession, reinforcing that when title is genuinely contested, the burden on the plaintiff increases, and a mere protective injunction is insufficient.

To provide an excellent outlook and prevent further injustice, the Court in S. Santhana Lakshmi created a temporary solution. While it set aside the injunction on interference, it maintained the injunction against alienation or encumbrance of the property. This strategic move preserves the status quo, the property remains safe from sale while granting liberty to both parties to initiate a proper, comprehensive suit for declaration of title and recovery of possession within three months.

Conclusion

The present judgement delivers a critical and timely message to property owners and legal practitioners alike. It serves as a stark reminder that judicial relief is a matter of strategic pleading as much as substantive right. By denying an injunction against interference where possession was admittedly with the defendant and title was under a cloud, the Supreme Court has re-established the foundational procedural requirement: In property litigation, a suit for injunction simpliciter is not a substitute for an action seeking declaration of ownership and recovery of possession. The ruling makes it clear that courts will not grant equitable remedies to circumvent the heavier but necessary burden of proving title and recovering actual possession when both are challenged. The liberty granted to the parties to file a fresh, comprehensive suit confirms the Court’s priority to ensure that substantive rights are settled on merits, not lost due to procedural flaws in pursuing a convenient, half-baked remedy.

Citations

- S. Santhana Lakshmi & Ors. v. D. Rajammal 2025 INSC 1197

- Anathula Sudhakar v. P. Buchi Reddy AIR 2008 SUPREME COURT 2033

- Rame Gowda (D) by LRs. v. M. Varadappa Naidu (D) by LRs. & Anr. AIR 2004 SUPREME COURT 4609

- T.V. Ramakrishna Reddy v. M. Mallappa CIVIL APPEAL NO. 5577 OF 2021

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla