Introduction

The contemporary legal focus has dramatically shifted, targeting the brazen impunity of those who would exploit a corporate debtor’s final hours. In the vulnerable era of corporate insolvency, the law’s sharpest instrument is now universally directed towards establishing an unyielding regime of accountability. The paramount objective is clear: to erect an absolute bulwark of deterrence against the fraudulent conduct of corporate insiders seeking to strip assets from the carcass of the Corporate Debtor. The NCLAT1 in Swapan Kumar Saha v. Ashok Kumar Agarwal2 has addressed this issue, the interpretation and application of Section 66 of the IBC3, specifically the relationship between its sub-sections (1) and (2) relating to fraudulent and wrongful trading, respectively.

The NCLAT, Principal Bench, New Delhi, adjudicated this matter, with the judgement rendered by Arun Baroka, Member (Technical). The core issue before the court was whether the requirements for fraudulent trading under Section 66(1) of the Code must be mandatorily read with the ‘due diligence’ test for wrongful trading under Section 66(2), or if the sub-sections operate independently of each other. The court ultimately held that Section 66(1) and Section 66(2) of the IBC are independent, self-contained provisions and do not need to be read conjunctively. It affirmed that an application for fraudulent trading under Section 66(1) can be maintained on its own.

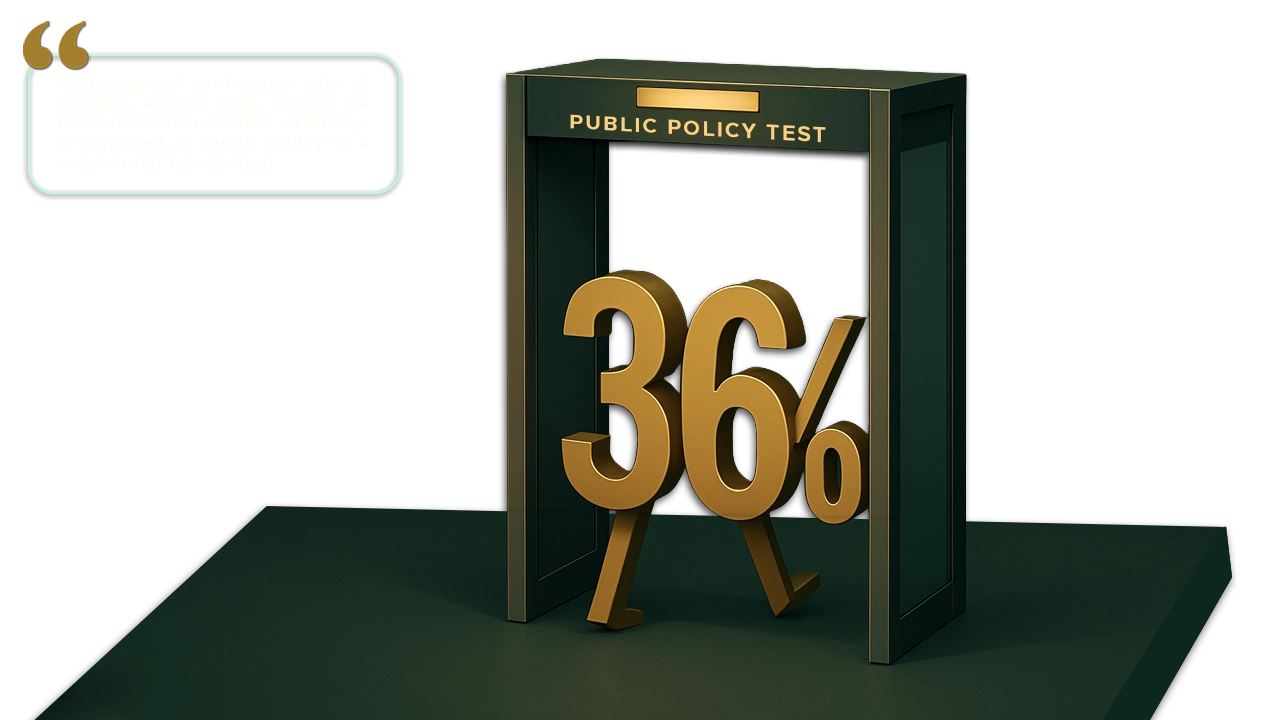

The dispute arose from an application filed by the erstwhile RP4/Liquidator against the Appellant, the Suspended Director of Corporate Debtor. The RP alleged that in 2013-14, the Appellant acquired some equity shares of a related party, from the CD5 for ₹ 8.80 lakh, despite the CD having acquired them in 2011-12 for ₹ 8.80 crores. This massively undervalued transaction allegedly caused a loss of ₹ 871.20 lakhs to the Corporate Debtor, leading the RP to seek a direction for the Appellant to contribute this amount, plus interest, to the CD’s assets under Section 66(2) of the IBC.

Fraud vs. Wrongful Trading: The Section 66 Independence Ruling

The Appellant’s contention was that the application filed by the RP lacked the necessary pleadings to satisfy the mandatory requirements for invoking Section 66 of the Code. Specifically, there were no pleadings regarding the fraudulent conduct of the CD’s business with the intent to defraud creditors, or the Appellant’s failure to exercise due diligence to minimise potential loss, as required for a Section 66 claim. The Appellant argued that Section 66(1) and 66(2) must be read conjointly, and an isolated transaction cannot constitute “carrying on business” with a fraudulent intent. Furthermore, the Appellant raised objections regarding the alleged bias of the erstwhile RP and the violation of the principles of natural justice by the AA6.

The Respondent’s contention focused on the blatant and undisputed facts demonstrating a fraudulent transaction, citing the sale of shares worth ₹ 8.80 crores for only ₹ 8.80 lakhs, and the fact that the CD’s bank account had already been declared a NPA7 earlier. The Respondent argued that Section 66(1) and Section 66(2) are self-contained and operate disjunctively, citing the legislative use of “or” between the sub-sections and the correlating criminal consequences under Section 67. The Liquidator stressed that fraud has no lookback period and that the Appellant failed to justify the loss or substantiate the claim of procedural injustice.

The NCLAT referenced several key judgments to analyse the relationship between Section 66(1) and Section 66(2) of the IBC. The Hon’ble Supreme Court in Hussain Ahmed Choudhury and Ors. v. Habibur Rahman (Dead) Through LRs and Ors8. cited to reiterate the existing position of legal interpretation that the disjunctive “or” cannot be read as a conjunctive “and”. This principle supported the Respondent’s argument that the two sub-sections of Section 66 operate independently. In Gopal Kalra v. Akhilesh Kumar Gupta9, Appellate Tribunal decision supported the view of independent applicability of Section 66(1). In the cases of Sangeeta Jatinder Mehta and Anr. v. Kailash Shah RP of New Empire Textile Processor Private Limited10 and Renuka Devi Rangaswamy v. Mr. Madhusudan Kemka11 NCLAT underscored the necessity of high-standard proof and necessary pleadings for invoking Section 66.

The analysis focused on the distinct ingredients of each sub-section. Section 66(1) requires proof of carrying on the business with intent to defraud creditors or for any fraudulent purpose, applying to any person knowingly party to it. Section 66(2) targets a director or partner who failed to exercise due diligence when they knew or ought to have known that insolvency could not be avoided. The NCLAT’s application of the “or” disjunctive in line with the Supreme Court’s ruling, as reflected in Section 67(1) and 67(2), meant that the Adjudicating Authority could proceed under either sub-section independently.

The NCLAT effectively resolved the dichotomy between reading Section 66(1) and 66(2) as conjunctive or disjunctive by aligning with the interpretation that they are self-contained and independent provisions. The Tribunal found no merit in the Appellant’s argument that Section 66(1) could not be made operational without recourse to Section 66(2). It was established that an application under Section 66(1) for fraudulent trading (which does not have a look-back period under the IBC) can be maintained even if the stricter ‘due diligence’ test and ‘knowledge of impending CIRP’ under Section 66(2) are not explicitly met, particularly when the RP’s application sought directions under Section 66(2) as well.

The NCLAT, after hearing both contentions and reviewing the material, upheld the Adjudicating Authority’s decision. The Tribunal confirmed that the undisputed facts regarding the sale of shares at a grossly undervalued price amounted to a fraudulent transaction falling under the ambit of Section 66, and the arguments regarding procedural lapse or the interplay of the sub-sections were not sufficient to overturn the order of contribution against the Appellant.

Conclusion

The case of Swapan Kumar Saha (Supra) is a significant ruling by the NCLAT that primarily addresses the scope and applicability of Section 66 of the IBC. The Tribunal affirmed that the provisions concerning fraudulent trading [Section 66(1)] and wrongful trading [Section 66(2)] are independent of each other. It established that an application concerning fraudulent business conduct can stand on its own, without requiring the additional criteria of ‘knowledge of impending CIRP’ and lack of ‘due diligence’ specified under Section 66(2). The decision also reinforced that the Appellant was not denied natural justice given the numerous opportunities provided by the Adjudicating Authority.

This judgment solidifies the power of the Resolution Professional and Liquidator to pursue directors and other parties involved in fraudulent transactions with a less restrictive scope. Fraudulent conduct under Section 66(1) requires no ‘due diligence’ test to be proven. By confirming that Section 66(1) and 66(2) operate independently, the NCLAT has ensured that the limitation for ‘look-back’ is not inadvertently applied to outright fraudulent transactions, which fundamentally operate outside a time constraint under the IBC framework for preferential, undervalued, or extortionate transactions influenced by fraud. This will serve as a powerful deterrent against directors attempting to strip assets of a Corporate Debtor, reinforcing the core objective of the IBC to maximise the value of the CD’s assets for all creditors.

This ruling prompts several questions for future legal discourse and practice. How will the NCLAT/NCLT clearly distinguish between the “intent to defraud” required under Section 66(1) and mere commercial misjudgment, especially in complex, related-party transactions? What standard of evidence will be required to prove a person was “knowingly a party” to the fraudulent conduct under Section 66(1) when the transaction occurred many years before the CIRP?

Citations

- National Company Law Appellate Tribunal

- Swapan Kumar Saha v. Ashok Kumar Agarwal, Company Appeal (AT) (Insolvency) No. 2355 of 2024

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016

- Resolution Professional

- Corporate Debtor

- Adjudicating Authority

- Non-Performing Asset

- Hussain Ahmed Choudhury and Ors. v. Habibur Rahman(Dead) Through LRs and Ors. [Civil Appeal No. 5470 of 2025]

- Gopal Kalra v Akhilesh Kumar Gupta CA (AT) (Ins) No. 567 of 2024

- Sangeeta Jatinder Mehta & Anr. v Kailash Shah (RP) CA (AT) (Ins) No. 104 of 2024

- Renuka Devi Rangaswamy (RP) v Regen Powertech Pvt. Ltd. CA (AT) (CH) (Ins) No. 357 of 2022

Expositor(s): Adv. Shreya Mishra