Imagine an arbitration, which is a faster, less formal alternative to court, grinding to a halt, not over the merits of the dispute, but because a party failed to pay the arbitrator’s fees. Does this technical termination seal the door forever, or can the aggrieved party simply open a new one? This procedural dilemma, one of many that continue to “plague the arbitration regime of India,” recently took center stage before the Supreme Court.

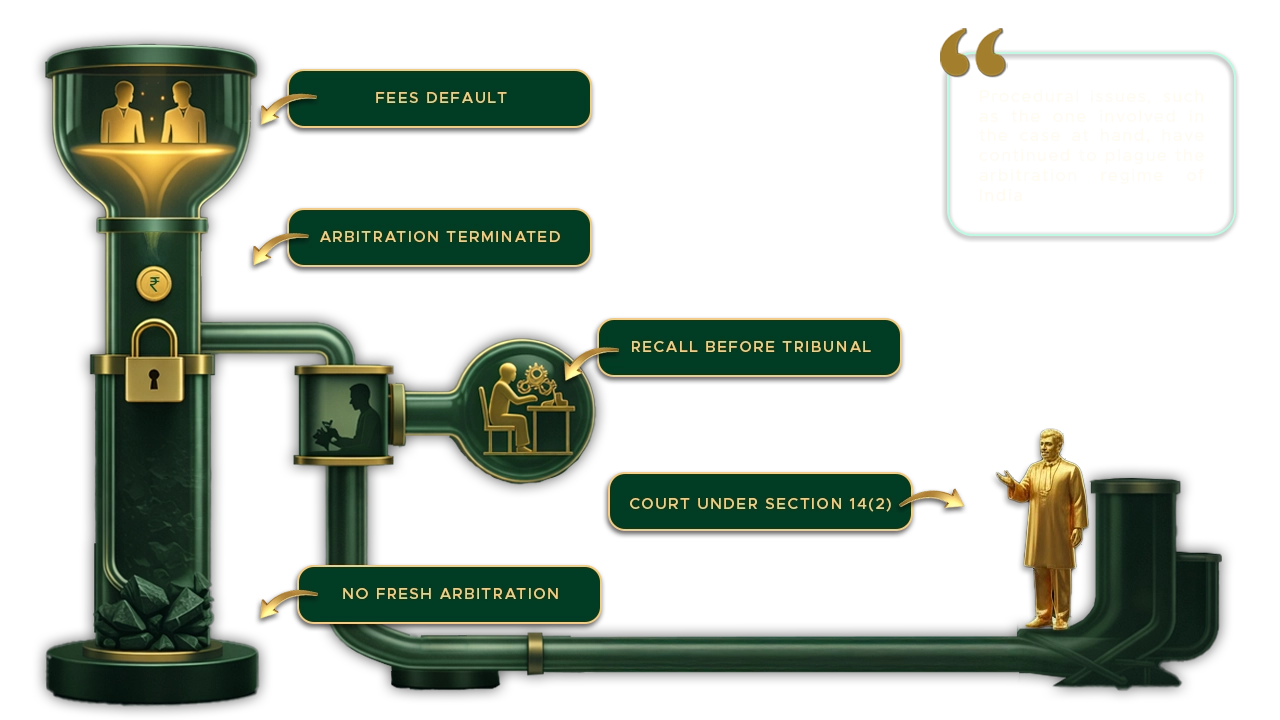

In a significant ruling in Harshbir Singh Pannu and Anr. v. Jaswinder Singh1, the Supreme Court unequivocally held that an Arbitral Tribunal is legally empowered to terminate proceedings under Section 38(2) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, when a party defaults on paying its share of the fee. Crucially, the Court clarified that the remedy for this specific termination is not to seek the appointment of a new arbitrator under Section 11, but rather to first seek a recall of the order before the tribunal itself. If that fails, the party must then approach the court under Section 14(2) for the termination of the arbitrator’s mandate. The fundamental issue before the bench of Justices JB Pardiwala and R Mahadevan revolved around the distinct legal effect of a proceeding’s termination under Section 38 (for non-payment) versus a termination of the arbitrator’s mandate under Sections 14 or 15 and the appropriate recourse available to the frustrated litigant.

The Court strongly criticized the current legislative framework, including the proposed Arbitration and Conciliation Bill, 2024, for failing to adequately address this ambiguity, stressing that a proper remedy against such a termination is “the need of the hour.” Moreover, the bench expressed a firm disinclination to allow parties to re-initiate arbitration proceedings once terminated due to their own fault, fearing this would grant a “mischievous party a license to forum shop without fear.” This article delves deep into the underlying legal principles that informed this authoritative judgment, examining the true meaning of ‘termination of arbitral proceedings’ under the 1996 Act and the implications for the future of Indian arbitration.

The Statute’s Silence: Where Does the Law Define “Termination”?

Given the critical nature of an arbitration’s conclusion, one might assume that the foundational statute, the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, provides a crystal-clear definition of what constitutes “termination of arbitral proceedings.” Yet, as the Supreme Court observed, the Act is conspicuously silent. It nowhere defines the expression; instead, it embeds the concept within various provisions, creating a fragmented and potentially confusing legal landscape. So, what are the specific pathways through which an arbitrator can legitimately bring the proceedings to an end, and are all these terminations created equal?

The Act outlines four distinct provisions under which an Arbitral Tribunal is empowered to terminate proceedings. The first is found in Section 25(a), which mandates termination when a claimant defaults in filing their statement of claim without sufficient cause. This is counterbalanced by Section 25(b) and (c), which prevent termination merely for the respondent’s failure to file a defence or a party’s non-appearance or non-production of evidence. In these scenarios, the Tribunal is generally required to continue the proceedings. This dichotomy highlights a legislative intent: to prevent a devious respondent from frustrating the arbitration process through inaction, while ensuring claimants meet their primary obligation.

The remaining three pathways include termination upon a settlement between the parties under Section 30(2), termination for non-payment of costs, including arbitrator’s fees, under Section 38(2), and finally, the residual power of termination under Section 32(2). This latter provision allows termination either by the claimant’s withdrawal, where the respondent has no legitimate interest in continuing, or by mutual agreement, or where the continuation has “for any other reason” become unnecessary or impossible. It is this maze of provisions, each with a different trigger, a different obligation, and potentially a different legal consequence, that demands careful legal scrutiny. Why does this nuanced distinction between the different termination clauses matter so profoundly for the fate of an arbitration? Because, as Section 32(3) clarifies, the termination of proceedings shall also terminate the mandate of the Arbitral Tribunal, divesting it of all further powers, save for limited functions like correcting or interpreting the final award. Understanding the specific nature of the termination is, therefore, paramount to determining what, if any, remedy remains for the aggrieved party.

The Locus of Power: Does Termination Flow Solely from Section 32(2)?

A fundamental question that dictates the remedy available to an aggrieved party is this: what is the ultimate source of the Arbitral Tribunal’s power to terminate the proceedings? While Sections 25, 30, and 38 outline distinct grounds for termination, default by the claimant, settlement by parties, and non-payment of fees, respectively, the overarching Section 32(1) states that proceedings conclude either by a final award or by an order under Section 32(2). This structural ambiguity has led to a significant cleavage of judicial opinion. Appellants frequently argue that all termination orders, regardless of the underlying cause, must ultimately be traced back to the residual clause of Section 32(2)(c), which permits termination when continuation has become “unnecessary or impossible.” But is this reading legally sound, or does it collapse the nuanced distinctions drawn by the Act?

One line of reasoning, prominently articulated by the Bombay High Court in Maharashtra State Electricity Board v. Datar Switchgear Ltd2., posits that Sections 25, 30, and 38 merely enumerate the occasions for termination, but the power to pass the order itself rests solely with Section 32(2). Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, as he then was, held that termination for specific defaults or for non-payment of costs, while triggered by the specific circumstances of Sections 25(a) or 38(2), must be effectuated through an order passed under Section 32(2). This perspective sees Section 32(2) as the procedural engine for all non-award terminations, including those based on the impossibility of continuing due to non-payment, an interpretation later echoed by the Supreme Court in Lalitkumar v. Sanghavi3 in the context of termination for lack of prosecution and fee default. Under this view, once an order is passed under Section 32(2), the arbitral mandate is terminated, making any recall or revival of the proceedings impossible.

However, a contrasting and equally compelling view treats the power of termination under Sections 25, 30, and 38 as independent of Section 32(2). The Supreme Court’s two-judge bench decision in SREI Infrastructure Finance Ltd. v. Tuff Drilling4, illuminated this distinction, particularly regarding termination under Section 25(a) for failure to file a claim. SREI Infrastructure argued that termination under Section 25(a) is fundamentally different from that under Section 32(2)(c) because the former occurs at an initial stage and does not explicitly mention the termination of the arbitral mandate, unlike Section 32. This omission, the Court reasoned, indicates that a tribunal retains the jurisdiction to recall a Section 25(a) termination if the claimant later shows sufficient cause. This interpretation, which was reiterated in Sai Babu v. M/s Clariya Steels Pvt. Ltd5., suggests that the termination of proceedings under Section 25(a) is not immediately co-terminous with the termination of the mandate, thereby carving out a vital remedy of recall that would be unavailable if the order were deemed to emanate from Section 32(2). This difference in the source of power is thus the crucial fault line in determining whether a terminated proceeding can be revived by the same tribunal.

The Unifying Principle: Is All Termination Equal Under the Act?

Having examined the divergent views on the source of the power to terminate, the central question remains: what is the singular legal effect of any termination under the Act? The Supreme Court, aiming to resolve the statutory friction, established a unified legal architecture. The Court decisively concluded that Section 32 of the Act is exhaustive and the only provision conferring the power on the tribunal to pass an order of termination. Consequently, Sections 25, 30, and 38 are not independent sources of power but merely denote the specific circumstances or triggers that enable the tribunal to take recourse to the termination order mandated by Section 32(2). In this integrated view, the omission of the phrase “the mandate of the Arbitral Tribunal shall terminate” in Sections 25, 30, and 38 is merely a descriptive difference, not a substantive one. Irrespective of the reason for termination, be it a final award, a claimant’s default, a settlement, or impossibility, the legal consequence is immutable: the arbitral reference stands concluded, and the authority of the tribunal is extinguished. This crucial finding brings uniformity to the law, rejecting the notion that a termination under one section might be revocable while another is final.

If all termination orders extinguish the tribunal’s mandate, does this seal the proceedings forever, thereby leaving the aggrieved party without any recourse before the very body that passed the order? The Court introduced a vital element of procedural fairness by drawing a clear distinction between a review on merits and a procedural review. It held that an Arbitral Tribunal inherently possesses the power for a procedural recall of its termination order. This power is limited to correcting an error apparent on the face of the record or addressing a material fact that was overlooked; it does not extend to revisiting substantive legal findings. Therefore, the appropriate first step for any party aggrieved by a termination order, including one for non-payment of fees under Section 38(2), is to file an application for recall before the very same Tribunal. This procedural gateway ensures the tribunal itself has the first opportunity to rectify a possible error of procedure or oversight. If, however, such procedural recall is unavailable or the arbitral tribunal declines to interfere, a limited recourse lies under Article 227 of the Constitution which is confined strictly to correcting jurisdictional or procedural errors, not to re-examining the merits of the arbitral dispute.

This leads directly to the question of appellate recourse: what happens if the recall application is either granted or dismissed? The Court laid down a precise, two-pronged legal pathway. If the Tribunal passes a favorable order, recommencing the arbitration, the opposing party’s only option is to participate in the revived proceedings and challenge the ultimate final award under Section 34 of the Act. Conversely, if the recall application is dismissed, the aggrieved party must then approach the Court under Section 14(2) of the Act. This judicial scrutiny allows the Court to examine whether the mandate of the arbitrator was legally terminated. If the Court finds the termination order to be contrary to law, it is empowered either to set aside the order and remand the matter back to the original Tribunal or, if warranted by the circumstances, proceed to appoint a substitute arbitrator under Section 15. This intricate framework ensures that while the Tribunal’s mandate is terminated upon order, the party is not left remediless and is channeled toward the appropriate forum for legal review.

The Legislative Imperative: Beyond Judicial Interpretation

The Supreme Court’s elaborate judgment, while resolving the immediate statutory conflict regarding termination for non-payment, ultimately shines a stark light on the profound inadequacies of the Indian arbitration regime itself. Despite the 1996 Act replacing the 1940 legislation and undergoing several amendments, the unsettling reality is that “procedural issues such as the one involved in the case at hand, have continued to plague the arbitration regime of India.” The most damning observation, perhaps, is that the proposed Arbitration and Conciliation Bill, 2024, presents a missed opportunity, having “taken no steps whatsoever to ameliorate the position of law as regards the termination of proceedings.” This legislative inertia maintains an uncertainty that, as the Court noted, is an “anathema to business and commerce.” This forces us to ask: If judicial interpretation is constantly required to unify fragmented statutory provisions, what concrete steps must Parliament take to fortify the foundation of arbitration law in India?

The Court strongly urged Parliament to intervene, providing a clear blueprint for legislative reform. Firstly, the numerous, contradictory termination provisions (Sections 25, 30, 32, and 38) should either be consolidated into a single provision or have their phraseology tweaked for consistency. Secondly, the new Bill must explicitly provide the nature and effect of termination, clarifying the authority of the Tribunal to entertain a recall application and recognizing this power by clearly delineating its extent and contours. Furthermore, the Court proposed the introduction of a statutory appeal under Section 37 of the Bill against an order terminating the proceedings, mirroring the appeal available against a ruling on jurisdiction under Section 16. These suggestions aim to eliminate the legislative gaps that necessitate repeated judicial intervention.

Finally, and perhaps most critically, the Court confronted the policy question of whether a contumacious party that wilfully causes termination by its own default should be allowed to have a “second bite at the cherry” by re-initiating arbitration. Citing international consensus that this issue must be regulated by national laws (Gary Born), the Court strongly opined that allowing an obdurate party to re-initiate arbitration would lead to a “chilling effect” and grant a “license to forum shop without fear.” Such a permissive approach would overburden an already strained system where the pendency of arbitration is “alarming,” potentially acting as the “death knell of arbitration.” The ultimate policy decision on barring the reintroduction of claims following a default-based termination must now be taken by Parliament, which the Supreme Court formally urged the Department of Legal Affairs, Ministry of Law and Justice, to address seriously while the Arbitration and Conciliation Bill, 2024, is still under consideration.

Citations

- Harshbir Singh Pannu and Anr. v. Jaswinder Singh, 2025 INSC 1400.

- Maharashtra State Electricity Board v. Datar Switchgear Ltd., 2002 SCC OnLine Bom 983.

- Lalitkumar v. Sanghavi, (2014) 7 SCC 255.

- SREI Infrastructure Finance Ltd. v. Tuff Drilling, (2018) 11 SCC 470.

- Sai Babu v. M/s Clariya Steels. Pvt. Ltd., Civil Appeal No. 4956 of 2019

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit, Nidhi Kumari (Intern)