Introduction

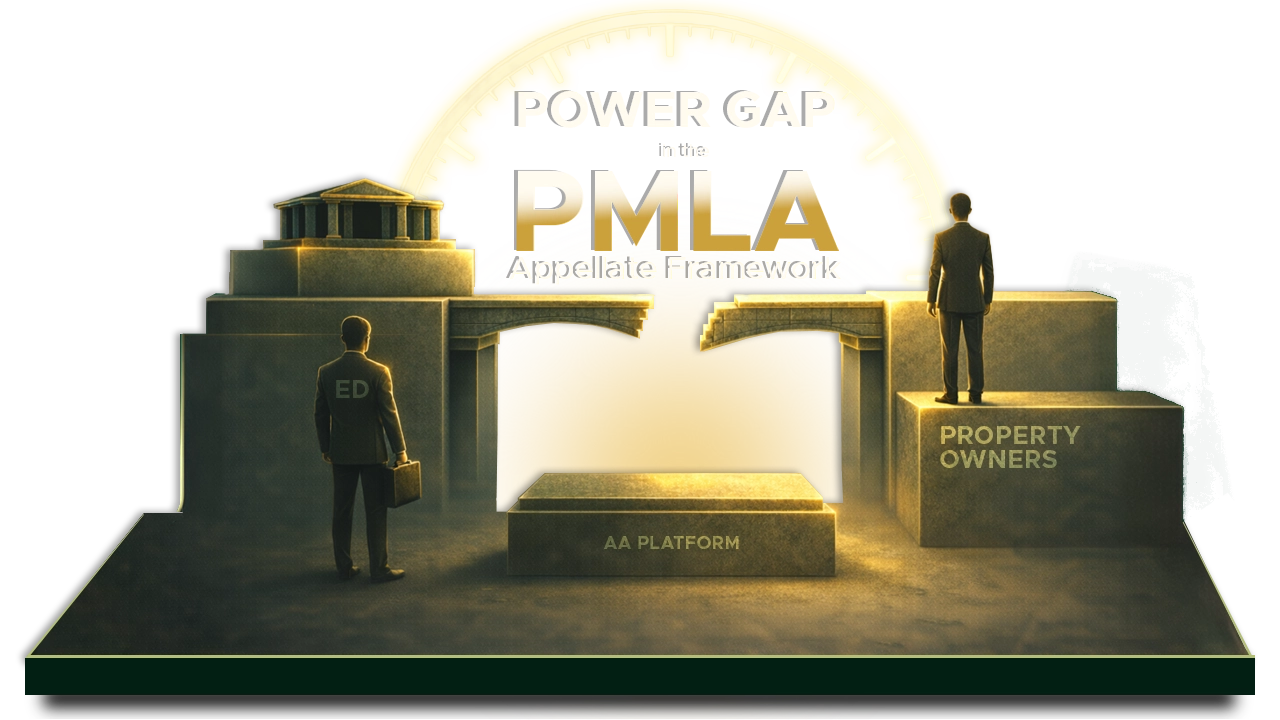

Can the PMLA Appellate Tribunal exercise a power that the law never explicitly granted it? This question lies at the heart of a growing legal debate surrounding the Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, 20021 (PMLA). While the Act was designed to create a robust system of checks and balances against the Enforcement Directorate’s (ED) vast powers of attachment, the procedural reality often tells a different story. When an attachment order is challenged, the PMLA Appellate Tribunal (PMLA-AT) frequently finds itself in a “power gap,” specifically regarding its authority to remand matters back to lower authorities for fresh consideration. This lack of explicit statutory backing has birthed a complex landscape of conflicting judicial interpretations and operational hurdles.

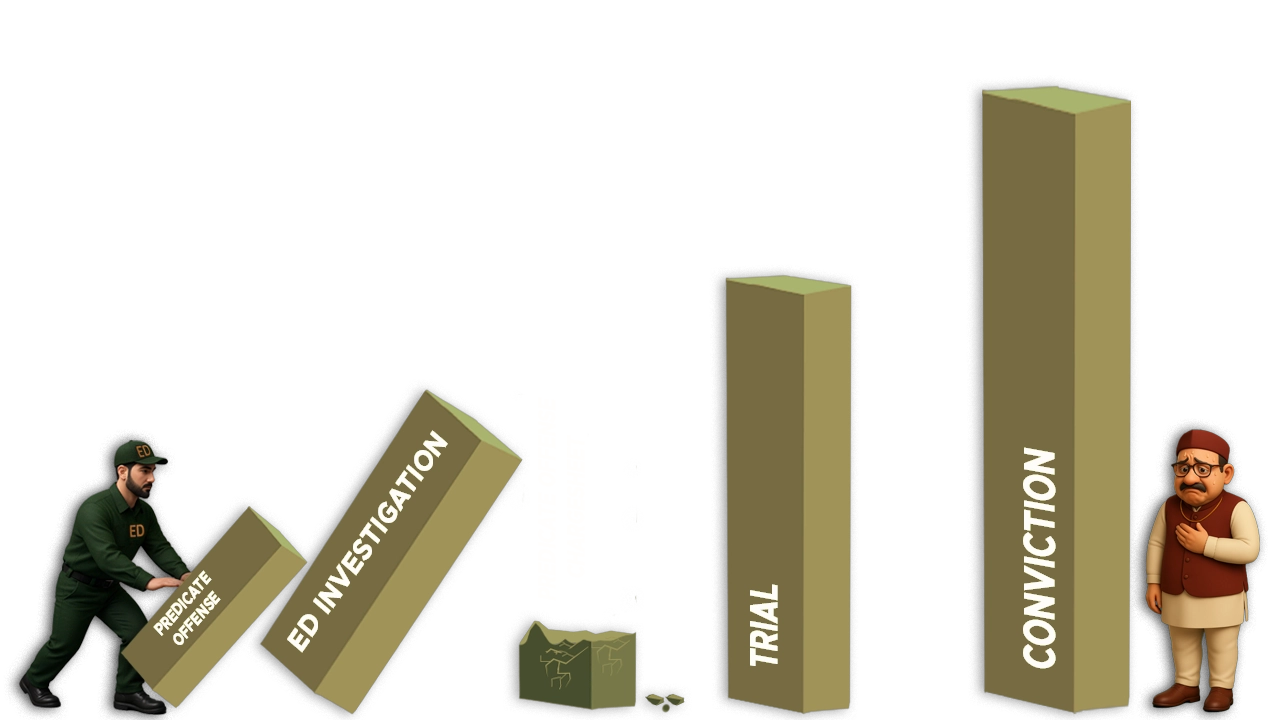

The statutory timeline of the property attachment under the PMLA follows a strict, time-bound trajectory. Under Section 52, the ED may provisionally attach property it believes to be “proceeds of crime.” Within 30 days, a complaint must be filed with the Adjudicating Authority (AA), which then has a total of 180 days from the date of attachment to either confirm or reject it.

Section 26(4) of the PMLA3 governs the powers of the Appellate Tribunal. It states that the Tribunal may pass “such orders as it thinks fit, confirming, modifying or setting aside” the order of the AA. Notably absent from this list is the word “remand.” Unlike other statutes that explicitly allow an appellate body to send a case back for a re-trial, the PMLA remains silent. This “power gap” forces a difficult question: Is the power to remand inherent in the power to “set aside,” or does the omission signify a deliberate legislative intent to prevent the ED from getting a “second bite at the apple”?

Judicial Conflict: Purposive vs. Literal Interpretation

The Indian judiciary is split on how to bridge this gap, drawing inspiration from varied precedents:

The Purposive Approach (Liberal Interpretation): Proponents of this view rely on Union of India v. Umesh Dhaimode4, where the Supreme Court interpreted the Customs Act. The Court held that the power to “annul” or “set aside” a decision naturally includes the power to remand, as a remand order effectively nullifies the original decision. This logic was adopted by the Calcutta High Court in Partha Chakraborti v. Enforcement Directorate5 and the Jammu & Kashmir High Court in Sarwa Zahoor v. Enforcement Directorate6. These courts argue that a literal reading would create a “paradoxical situation” where the Tribunal, after finding a procedural error, would be powerless to direct a fresh, merit-based review.

The Literal Approach (Strict Interpretation): Conversely, the Karnataka High Court in Enforcement Directorate v. Devas Multimedia (P) Ltd7. took a stricter stance, leaning on the Supreme Court’s ruling in MIL India Ltd. v. CCE8. In that case, the Court held that if the legislature deliberately amends a statute to remove a power of remand, that power cannot be read back into it. The Karnataka High Court emphasized that without express authorization in Section 26(4), the PMLA-AT lacks the jurisdiction to remand matters to the AA.

Even if one accepts that the PMLA-AT possesses the inherent power to remand, the exercise of this authority triggers a cascade of practical and operational risks that threaten the stability of the attachment process. The primary challenge lies in the strict 180-day statutory clock prescribed for the confirmation of provisional attachments. By the time a matter reaches the appellate stage and is subsequently remanded, this period has almost invariably lapsed. Because the PMLA provides no mechanism to “pause” or “extend” this timeline during the pendency of an appeal, a remanded order often returns to the Adjudicating Authority (AA) at a time when the legal basis for the attachment has already expired due to the efflux of time.

This creates a significant procedural vacuum. While the Supreme Court in Kaushalya Infrastructure Development Corpn. Ltd. v. Union of India9 suggested that adjudication proceedings can technically operate independently of the provisional attachment order, the practical reality is fraught with uncertainty. In the Partha Chakraborti and Sarwa Zahoor cases, High Courts ruled that a remand restores the AA to its original position, allowing adjudication to continue. However, if the attachment itself has ceased to exist, the property may be alienated before a fresh order is passed. Furthermore, the PMLA is silent on the timeline for completing these “second-round” proceedings. Without a court-mandated deadline, remanded cases risk entering a state of indefinite litigation, undermining the legislative intent of expeditious disposal and leaving property rights in a perpetual state of limbo.

Conclusion: The High Stakes of Procedural Ambiguity

The ambiguity surrounding the remand powers of the PMLA-AT represents far more than a technical glitch; it is a fundamental tension between the state’s power to seize and the citizen’s right to finality. While judicial interpretations in Partha Chakraborti and Sarwa Zahoor have attempted to fill this silence with a “purposive” spirit ensuring that procedural errors do not grant a free pass to potential money launderers this expansion of power exists on fragile ground. Without the express legislative blessing found wanting in the Devas Multimedia and MIL India perspectives, every remanded case carries the risk of being struck down as an ultra vires act of the Tribunal.

The implications are twofold and equally concerning. For the Enforcement Directorate, a remand in the absence of a live attachment order creates a “paper tiger” scenario: the adjudication continues, but the property, the very heart of the proceeds of crime may vanish during the delay. For the property owner, the lack of a statutory timeline for remanded proceedings creates a “legal purgatory,” where assets remain tied up in a cycle of litigation that the PMLA’s original 180-day mandate was specifically designed to prevent. Ultimately, until the legislature bridges this “power gap” with clear amendments, the remand process will remain a high-stakes gamble, leaving both the efficacy of the law and the protection of civil liberties in a state of precarious uncertainty.

Citations

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla, Srijan Sahay (Intern)