The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC), heralded a new era for debt resolution in India. Envisioned as a comprehensive framework, it aimed to streamline and expedite the reorganisation and insolvency processes for corporate entities, partnership firms, and individuals alike, with the overarching goal of maximising asset value. While the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) under the IBC has demonstrably transformed the landscape of corporate debt restructuring, a crucial component remains conspicuously absent: the full operationalisation of Part III, which specifically addresses insolvency resolution and bankruptcy for individuals and partnership firms.

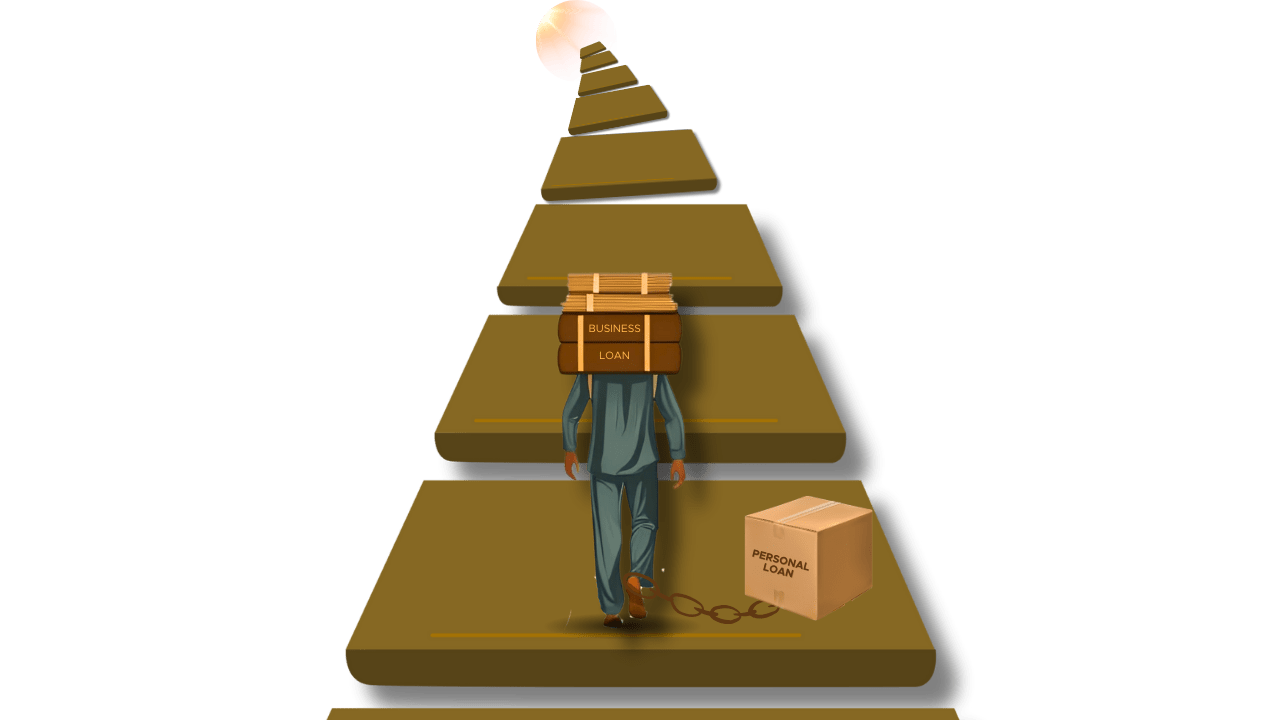

This protracted delay in notifying the individual insolvency provisions has left a significant portion of the Indian economic fabric, encompassing most individuals, proprietorships (which form the backbone of the nation’s micro, small, and medium enterprises), and non-limited liability partnerships, tethered to this legislation. The Presidency Towns Insolvency Act, 1909 (PTIA), and the Provincial Insolvency Act, 1920 (PIA), relics of a bygone colonial era and shaped by the political economy of the time, continue to govern these crucial segments. These outdated laws are not only inefficient in addressing the complexities of modern financial distress but also fail to provide a fair and effective mechanism for individuals and small businesses grappling with unsustainable debt.

The urgency for a robust individual insolvency framework has become increasingly palpable against the backdrop of escalating financial strain among individual borrowers. A looming crisis in the subprime lending sector, particularly within microfinance – small, unsecured loans vital for millions of self-employed individuals and those in precarious employment – underscores this need. Recent surveys revealing distress among a staggering 68% of such borrowers, coupled with the alarming trend of 27% resorting to new loans to service existing ones, paint a stark picture of a sector teetering on the brink of widespread defaults. Without a structured and legally sound debt resolution process, these vulnerable borrowers are trapped in a vicious cycle of debt, devoid of meaningful legal recourse.

This article delves into the multifaceted realm of individual insolvency, analysing diverse global approaches and scrutinising the shortcomings of the current Indian regime. By drawing comparisons with established legal frameworks in countries like the USA and the UK, the aim is to identify a well-rounded solution tailored to the Indian context. Furthermore, this analysis will explore potential avenues to address the existing loopholes and limitations, paving the way for a more effective and just system for individual insolvency in India.

IBC on Individual Insolvency

The IBC lays out two primary pathways for addressing individual insolvency: the Insolvency Resolution Process (IRP) culminating in potential bankruptcy, and the Fresh Start Process (FSP) designed for individuals with limited means. The IRP applies to individuals and partnership firms whose total debts exceed a threshold limit specified by the government (currently set at ₹1,000). This process offers a more structured framework for debt resolution, involving the appointment of a Resolution Professional (RP) to oversee the proceedings. The core objective of the IRP is to facilitate a negotiated repayment plan agreed upon by both the debtor and their creditors.

Initiation of the IRP can be triggered by either the debtor or a creditor by filing an application with the appropriate Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) under Sections 94 and 95 of the IBC. Upon receiving the application, the DRT appoints an RP who is tasked with reviewing the application and providing a recommendation for its acceptance or rejection.

Designed for low-income individuals with limited assets, the FSP enables the discharge of qualifying debts, offering a fresh financial start. Section 80 of the IBC outlines eligibility criteria: gross annual income not exceeding ₹60,000, aggregate asset value not exceeding ₹20,000, aggregate qualifying debt not exceeding ₹35,000, no dwelling ownership, not an undischarged bankrupt, and no prior FSP admitted in the preceding 12 months. The RP evaluates the application and recommends acceptance or rejection to the DRT. Upon admission, a six-month moratorium on qualifying debts is imposed. Following the moratorium, the DRT issues a discharge order for these debts.

The Crucial Role of the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT)

In individual insolvency under the IBC, the DRT’s role is broader than in corporate insolvency. It approves IRP initiation based on the RP’s report and can approve or reject the repayment plan submitted by the RP, potentially providing implementation instructions or requiring modifications. This enhanced role underscores the DRT’s central position in ensuring fairness and effectiveness.

A Global Lens: Diverse Approaches to Individual Insolvency

The World Bank’s 2014 Report highlights diverse global practices, emphasizing the benefits, drawbacks, and challenges of various approaches. Informal negotiation is crucial but challenging in individual insolvency due to creditors’ enforcement demands. Most nations have court-based regimes, while some high-income countries use administrative strategies, necessitating consideration of existing institutions and intermediaries. Financial barriers can be mitigated through cost reduction, summary procedures, and technology. Exemptions, shielding some assets for basic needs post-insolvency, are vital for a ‘fresh start’. Many regimes require future income contributions for debt discharge, raising issues of baseline costs, fair payment expectations, and plan duration.

Individual Insolvency Laws in the USA: The United States bankruptcy law offers two distinct personal bankruptcy procedures under Chapter 7 (liquidation) and Chapter 13 (repayment plan). A key distinction lies in the source of repayment: Chapter 7 mandates repayment from the debtor’s assets, while Chapter 13 requires repayment from future income. The Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act, 2005 (BAPCPA), introduced significant changes, including predetermined income exemptions, aiming to address loopholes and ensure a more equitable balance between debtor relief and creditor rights. Prior to BAPCPA, debtors filing under Chapter 13 had greater flexibility in proposing repayment plans, sometimes leading to minimal or token payments, particularly if their assets were largely exempt.

Individual Insolvency Laws in England: In England and Wales, bankruptcy serves as a legal avenue for debt relief for individuals facing insurmountable financial obligations. A bankruptcy order, issued by a judge, can be initiated either by the debtor’s application or by a creditor if the debt exceeds £5,000 and certain conditions are met. Notably, in most cases, bankrupt individuals are permitted to retain essential assets, including their car and personal belongings. A significant feature of the English system is the relatively short discharge period, typically 12 months from the bankruptcy order, after which remaining debts are usually written off. Debt Relief Orders (DROs), introduced in 2009, provide a streamlined alternative to bankruptcy for individuals with debts under £15,000 and limited assets and disposable income, offering a viable solution for those with minimal capacity to repay.

Analysis and Charting the Way Forward for India

Comparing global bankruptcy policies highlights key parameters: debt discharge amount, asset/income exemptions, repayment duration, costs, and penalties. India should adopt a moderately debtor-friendly strategy, learning from the US post-BAPCPA, without unduly harming creditor interests. The FSP’s low eligibility threshold could strain the legal infrastructure. The DRT’s crucial role necessitates measures for speedy and effective case disposal, mirroring corporate insolvency timelines.

Implementing personal insolvency under the IBC will impact a credit market shaped by decades of weak debtor rights, particularly sensitive to debt forgiveness in the agricultural sector. Laws must balance creditor and debtor interests. For debtors, it should offer temporary debt collection halts, repayment plans, and eventual discharge of unsustainable debts. The competence and regulation of Insolvency Professionals are crucial. Navigating the IBC process will be complex for debtors, requiring guidance on filing decisions, procedures, RP engagement, discharge timelines, and credit rating impacts. Addressing potential social stigma through support and counselling, potentially through ‘credit counsellors’ or ‘debt advisors’ (currently lacking explicit mention in the IBC but noted in IBBI draft rules), is essential.

Conclusion

Credit markets are indispensable for fostering economic growth, facilitating consumption smoothing, and promoting entrepreneurial activity. The significance of well-designed insolvency laws in underpinning the expansion and stability of credit markets cannot be overstated. This analysis has highlighted several critical policy challenges that must be addressed to ensure the effective implementation of individual insolvency under the IBC. The ultimate success of this framework hinges on the careful crafting of subordinate legislation and the robust development of the necessary institutional infrastructure. Individual insolvency cannot achieve its intended impact without high-quality rules, significant enhancements to the institutional landscape, including the information utilities and DRTs, a cadre of skilled insolvency professionals, and the availability of effective bankruptcy consulting services. By addressing these crucial elements, India can unlock the untapped potential of individual insolvency, providing a vital safety net for financially distressed individuals and fostering a more resilient and equitable economic environment for all.