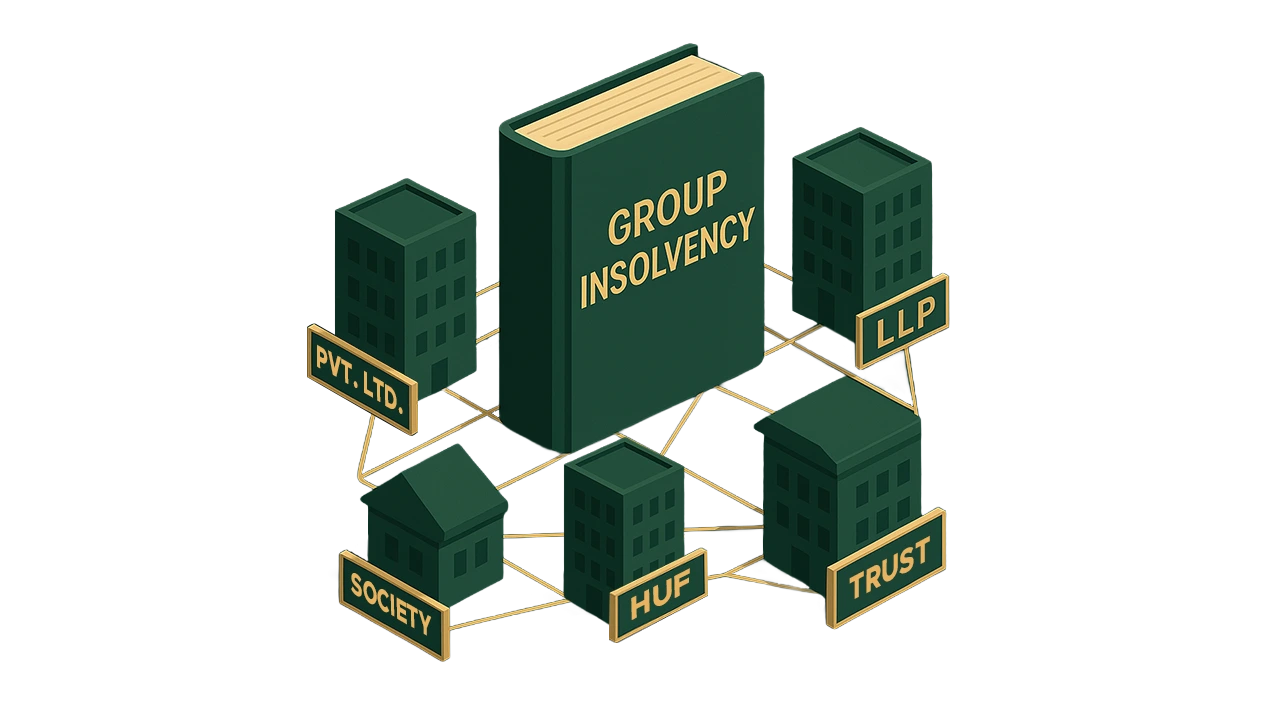

The corporate landscape often presents a complex web of interconnected entities, operating under a common umbrella yet maintaining distinct legal identities. But what happens when one or more threads of this web begin to fray, threatening the stability of the entire structure? How does the legal framework in India address the insolvency of such a group, where individual companies, despite their separate legal status, are deeply intertwined in their operations, finances, and ownership? This question of “group insolvency” has long been a point of discussion and judicial contemplation in India, particularly under IBC1.

Consider, for instance, a hypothetical scenario where Mr. Y establishes a listed company to own and operate hospitals across the country. This company acts as a holding entity, deriving royalties from the hospitals for consultancy services. The hospital buildings themselves are owned by an unlisted, wholly-owned subsidiary that secures bank loans for construction. Further layers of complexity are added as construction is managed by other subsidiary companies, majority-owned by Mr. Y and his non-corporate associates, and daily hospital operations are serviced by promoter-owned non-corporate entities.

Initially, this elaborate structure functions seamlessly, reassuring various agencies dealing with the group that they are engaging with a unified whole, spearheaded by the individual promoter. It is a common and commercially sound practice for businesses to operate through groups, with each entity having a separate legal personality, often to isolate specific assets from general liabilities and secure more favourable funding conditions. When these businesses are solvent, the prevailing perception is indeed that they operate as a single, unified group in the eyes of customers, suppliers, and creditors. Lenders frequently seek guarantees from the ultimate parent and principal individual promoters, readily provided, often overlooking formal divisions under the impression of dealing with the group as one.

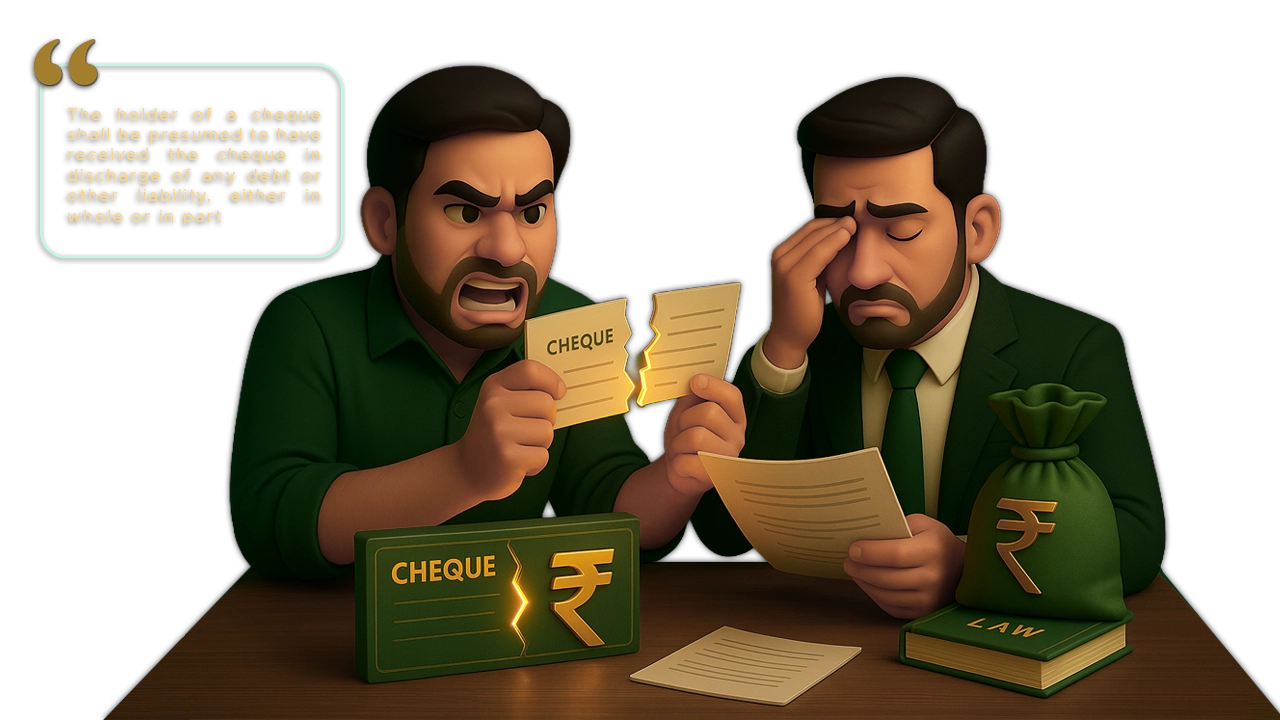

However, this very group structure can present opportunities for promoters and key personnel to manipulate the corporate form, evading regulations and responsibilities. This leads to significant confusion regarding inter-se liabilities and asset ownership. In our example, the promoters began to betray the trust of lenders by discontinuing service contracts with group entities monitored by banks and awarding them to ‘related’ entities outside the group on undisclosed terms. Hospitals started diverting monthly dues into current accounts with other banks outside the consortium, citing poor service. Banks, which initially received full loan installments, started receiving paltry amounts, with promoters attributing it to poor business conditions and rising costs. This eventually leads to multiple restructuring attempts under RBI schemes, and when these options are exhausted, the promoter seeks protection under IBC by filing for insolvency.

The traditional approach to such situations views each legal entity as a stand-alone body, solely liable for its own debts with only its own assets, regardless of its group affiliation. This perspective overlooks the reality that, throughout its operational life, the company was an integral part of a larger economic entity and was treated as such. The true size and complexity of many enterprise groups are often not apparent, as their public image is frequently that of a unitary organization under a single corporate or promoter identity. The legal structure of a group as separate entities often does not reflect the internal management of the group’s business. Crucially, the interrelationships that define how a group operates when solvent are typically severed once insolvency or restructuring proceedings commence.

In the case of our hypothetical hospital group, the involvement of non-corporate entities like hospital societies and LLPs, which fell outside the ambit of the IBC, prevented lenders from accessing crucial fund streams. These entities were, by design, shielded from the banks, effectively pre-meditating a plan where the IBC’s reach did not extend to them. This ultimately led to the loan accounts turning into NPAs2, and subsequent transaction audits during CIRP3 revealed significant irregularities, forcing banks to declare the company fraudulent and the promoter a willful defaulter.

This highlights a pressing need to broaden the Ministry of Corporate Affairs’ definition of ‘group’ to encompass non-corporate entities, while still retaining the criteria of significant control and substantive ownership for determining the ‘group’ character. Furthermore, the definition of ‘related parties’ under Section 5(24) IBC, which currently covers group corporates, LLPs, and Key Managerial Personnel, needs to be expanded.3 Without consolidation, achieving an effective resolution for the hospital-owning company would be difficult. The absence of consolidation would likely lead to inefficiencies, loss of value, lack of coherence, multiplied costs, conflicting decision-making, and increased uncertainty of outcome. Generally, consolidation would be in the best interests of creditors, who would suffer greater prejudice without it than the insolvent companies or objecting creditors would from its imposition.

In the case of “procedural coordination,” it is deemed appropriate to initiate CIRP4 against group corporate entities before NCLT5. The Cross-Border Insolvency Rules/Regulations Committee (CBIRC), established by the MCA, in its report dated December 10, 2021, reiterated suggestions from IBBI Working Group regarding the operational methodology for CIRP under procedural coordination. The Working Group, in its December 10, 2019 report, had recommended that the Group Insolvency framework should be “enabling” and allow for voluntary adoption by stakeholders. It further suggested a phased introduction, starting with procedural coordination for group corporates (holding, subsidiary, and associate companies) with some flexibility for the Adjudicating Authority to define the grouping, followed by cross-border and substantive variants. Mandatory provisions envisioned by the Working Group included a joint application for insolvency, communication and information sharing among group committee members, an Insolvency Professional, Adjudicating Authority, and a group coordination structure among different lenders to the group entities. However, these remain to be formalised.

Despite the absence of a comprehensive Group Insolvency Framework, the NCLT benches have proactively applied principles of group insolvency on a case-by-case basis to uphold the objectives of the IBC. A landmark instance is the insolvency of Videocon Industries6, where NCLT Mumbai allowed the consolidation of insolvency proceedings for 13 of the 15 entities within the Videocon Group. This decision was based on the inextricable links in their operations and their involvement in composite loan agreements. Other crucial factors supporting consolidation included common control, assets, directors, and liabilities; interdependence of companies; interlacing of finance; pooling of resources; co-existence for survival; intricate links between entities; intertwined accounts; inter-looping of debts; singleness of economic activity; and common financial creditors. Similarly, during the insolvency of Lavasa Corporation, the NCLT Mumbai permitted the consolidation of insolvency proceedings for Lavasa Corporation and its four wholly-owned subsidiaries. This was justified by the fact that Lavasa Corporation guaranteed the debts of all four subsidiaries, and the resolution plan was conditional on the consolidation of all entities’ insolvency processes. The NCLAT7 has also ordered procedural coordination for insolvency proceedings through a single IP before a single AA for five entities that jointly owned a plot of land and operated as a consortium in Edelweiss Asset Reconstruction Co Ltd v. Sachet Infrastructure Pvt Ltd & Ors.8

It is incumbent upon the NCLT to act innovatively and creatively to advance IBC’s objectives, filling legislative gaps through judicial decisions and interpretations. Even other group entities with different legal structures would benefit, as they would be able to address contractual and other relationship issues with the defaulting company arising from the insolvency resolution process.

In conclusion, the consolidation of insolvency proceedings must align with the objectives of the IBC. The existing laws and judicial pronouncements on group entities, where the piercing of the corporate veil is paramount in upholding the IBC’s objectives of providing the best possible outcome for all stakeholders, are largely sufficient to address emerging situations. What is truly needed is for the judicial infrastructure to adopt a proactive mindset and deliver robust outcomes. The IBBI’s discussion paper floated on February 4, 2025, titled “Streamlining Processes under the Code: Reforms for Enhanced Efficiency and Outcomes”9 includes a proposal on “Coordinated Insolvency Resolution for Interconnected Entities,” which is a significant step towards a formalised Group Insolvency Framework under the IBC. The future of group insolvency in India lies in a framework that embraces the economic reality of interconnected entities, ensuring a just and efficient resolution process that maximises value for all stakeholders.

Citations

- IBC – Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code

- NPA – Non-Performing Assets

- Report of the Working Group on Group Insolvency, (September 2019), p. 30 <https://www.ibbi.gov.in /uploads/resources/d2b41342411e65d9558a8c0d8bb6c666.pdf>

- CIRP – Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

- NCLT – National Company Law Tribunal

- SBI v. Videocon Industries Ltd. (2018 SCC OnLine NCLT 13182)

- NCLAT – National Company Law Appellate Tribunal

- Company Appeal (AT) (Insolvency) No. 377 of 2019

- Streamlining Processes under the Code: Reforms for Enhanced Efficiency and Outcomes

Expositor(s): Adv. Khushboo Saraf