Introduction

In the complex tapestry of international commercial law, the enforcement of a foreign arbitral award in India presents a fascinating interplay of domestic statutes and international obligations. A common misconception is that once an arbitral award is rendered in a foreign jurisdiction, its automatic enforcement in India is guaranteed. However, as the Delhi High Court judgement in Roger Shashoua & Others Versus Mukesh Sharma & Others1 and a long line of judicial precedents have clarified, this process is far from automatic. It requires a formal legal proceeding that carefully balances the principles of comity and the sanctity of due process.

The journey of a foreign arbitral award to becoming a legally binding and executable decree in India is governed by a precise legal framework. A crucial point, as noted by the Delhi High Court, is that an award, even after it is deemed enforceable, does not automatically transform into a decree. This is a critical distinction that sets foreign arbitral awards apart from foreign court decrees. CPC2, in its Section 44A, provides for the direct execution of decrees from courts in “reciprocating territories.” Yet, as Explanation 2 to this very section clarifies, an “arbitration award” is expressly excluded from the definition of a “decree,” even if it is enforceable as one. This legislative nuance underscores the need for a specific, separate procedure for the enforcement of foreign awards.

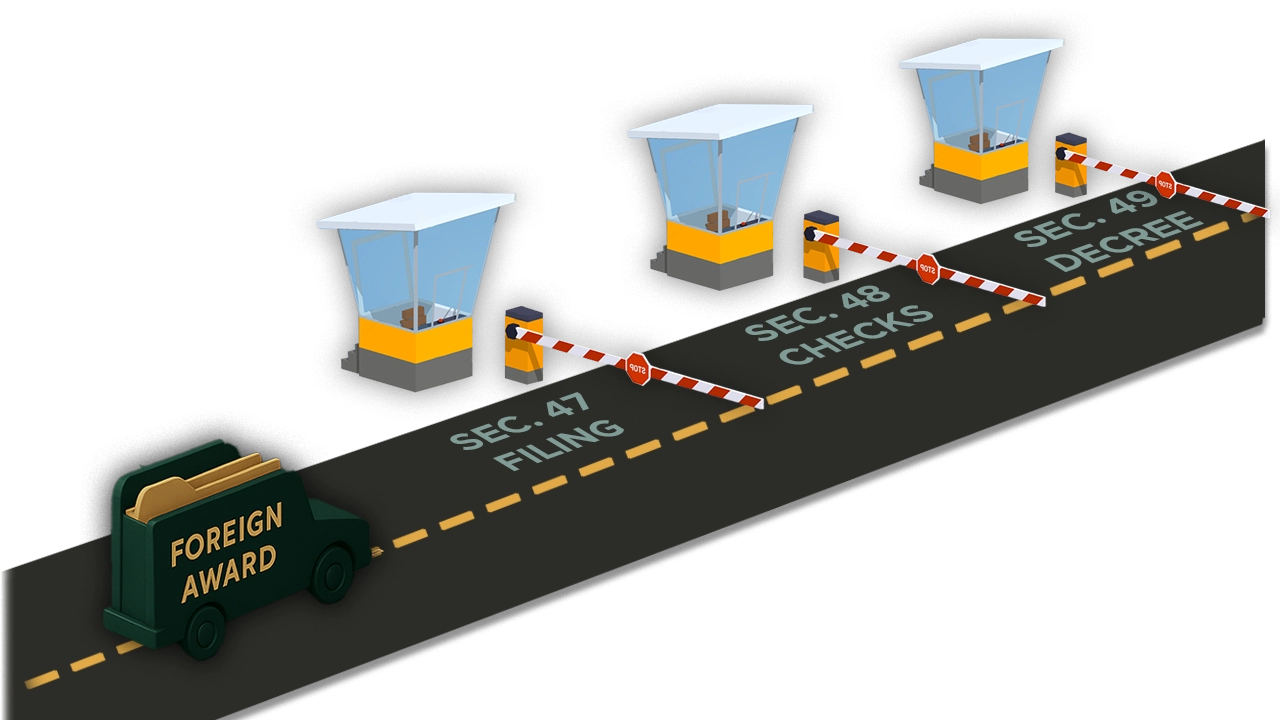

So, what is the path to enforcement for a foreign award? A party seeking to enforce a foreign award must file a petition under Sections 47 and 49 of the A&C Act3. This procedural requirement was cemented by the Delhi High Court’s decision in Furest Day Lawson Ltd. v. Jindal Exports Ltd4., which observed that the award becomes a decree of the court only after it has been held to be enforceable. The Supreme Court, in Government of India v. Vedanta Limited5, further clarified the legal landscape by ruling that the limitation period for filing such a petition is governed by Article 137 of the Limitation Act, 1963, not Article 136, as a foreign award is not considered a decree of a Civil Court in India.

This journey from award to decree highlights a crucial shift in legal responsibility. Once the award-holder has met the procedural requirements of Section 47, the onus is no longer on them to prove the award’s validity. Instead, the burden shifts to the party opposing enforcement, who must now justify their challenge on the limited grounds provided in Section 48 of the A&C Act. But what exactly are these grounds, and why are they so strictly defined?

The answer lies in India’s commitment to the New York Convention of 1958, which it adopted to foster a uniform international scheme for the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. The convention, through its Article III, obligates signatory states like India to enforce foreign awards. To give effect to this, Part II of the A&C Act, 1996 incorporates the Convention’s principles. At the heart of this framework is Article V of the New York Convention, which provides an exhaustive and limited set of grounds for refusing enforcement.

This pro-enforcement ethos is a cornerstone of international arbitration. As noted by legal scholars like Albert Jan Van Den Berg and reaffirmed by the Delhi High Court, courts cannot simply review the merits of a foreign award. This principle, as highlighted in the Delhi High Court’s judgment in Glencore Grain Rotterdam B.V. v. Shivnath Rai Harnarain (India) Co6., emphasizes that if an award does not suffer from any of the defects listed in Section 48(1) and (2), it must be enforced. The Supreme Court, in Avitel Post Studioz Limited & Ors. v. HSBC PI Holdings (Mauritius) Limited7, echoed this by stressing that minimal judicial intervention is the norm.

One of the most frequently invoked, yet narrowly interpreted, grounds for challenge is that of “public policy.” Section 48(2)(b) of the A&C Act allows for the refusal of an award if it is found to be in conflict with the public policy of India, which is further defined as being induced by fraud or corruption, in contravention of the fundamental policy of Indian law, or in conflict with the most basic notions of morality or justice. The Supreme Court, in Renusagar Power Co. Ltd. v. General Electric Co8., first held that “public policy must be construed in a narrow sense”, a view consistently followed in Indian jurisprudence and subsequently affirmed by the 246th Law Commission Report.

Does this mean that a court can never look into the merits of a case, even if there appears to be a clear error? The judiciary has been firm on this. As illustrated in the Delhi High Court’s analysis, the scope of inquiry under Section 48 does not permit a “second look” at the award on its merits. Even procedural defects, such as an arbitral tribunal considering inadmissible evidence or ignoring binding evidence, do not necessarily provide a basis to refuse enforcement on the grounds of public policy. This was the view of the Supreme Court in a case where it was held that even if the Board of Appeal erred in relying on a report inconsistent with the contract, such errors would not bar the enforceability of the award.

The journey of foreign award enforcement has been marked by significant shifts in judicial thinking. A notable example is the evolution of law regarding the applicability of Part I of the A&C Act to foreign arbitrations. Initially, in Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading S.A. and Anr9., the Supreme Court held that Part I was applicable to international commercial arbitrations held outside India, unless specifically excluded by the parties. This position, however, was later overruled by the landmark decision in Balco v. Kaiser Aluminium Technical Services Inc10., which unequivocally held that Part I applies only to arbitrations seated in India. This ruling brought much-needed clarity, establishing that foreign awards cannot be challenged under Section 34 of the A&C Act, a point affirmed by the Supreme Court in Roger Shashoua and others v. Mukesh Sharma and others11.

The law has also evolved regarding the enforceability of an award while it is under challenge. The previous position, as seen in National Aluminum Co. Ltd. v. Pressteel & Fabrications (P) Ltd. & Anr12., was that the filing of a Section 34 petition rendered the award not executable. The Mumbai High Court, in AFCONS Infrastructure Ltd. v. The Board of Trustees of the Port of Mumbai13, further observed that an award could not be enforced if it was challenged within the limitation period. However, the Arbitration Amendment Act14, drastically changed this by amending Section 36(2). The new provision states that merely filing an application to set aside an award does not render it unenforceable. A separate application for a stay of the award is now required, a move that significantly strengthens the pro-enforcement stance of Indian law.

While the legal framework emphasizes limited judicial interference, does this rigid approach completely ignore principles of equity and fairness? The judiciary recognizes the need for a more flexible approach in arbitral proceedings, as long as the tribunal remains within the legal framework. In Batliboi Enviornmental Engineers v. Hindustan Petroleum Corpn. Ltd. & Ors15., the Supreme Court acknowledged that at times, arbitral tribunals may act on principles of equity, and such decisions can be just and fair. This balanced view underscores that while courts will not re-examine the merits of a foreign award, they acknowledge that the arbitral process itself can, and at times should, incorporate equitable considerations.

The journey of a foreign arbitral award in India is thus a testament to a legal system that is both committed to its international obligations and grounded in its own procedural requirements. It is a system that demands a clear and deliberate process for enforcement, a system that places the burden of challenge on the opposing party, and a system that upholds the principle of minimal judicial intervention, all in service of fostering a reliable and predictable environment for international commerce.

Conclusion

The judicial pronouncements discussed herein, particularly those from the Delhi High Court and the Supreme Court, paint a clear and resolute picture: India’s legal framework for enforcing foreign arbitral awards is robust and firmly aligned with the pro-enforcement ethos of the New York Convention. The journey from a foreign award to an executable decree is not an automatic one but a procedural path that places a clear onus on the parties and limits judicial intervention to the narrow grounds stipulated in Section 48 of the A&C Act. By upholding a narrow interpretation of “public policy” and confirming that Indian courts cannot conduct a “second look” at the merits of a foreign award, the judiciary has fortified India’s commitment to international commercial arbitration. This clarity and predictability in the legal landscape are indispensable for fostering investor confidence and promoting India as a reliable destination for international commerce.

As we look to the future, several questions and implications arise from this settled legal position. With the framework for enforcement now well-established, will the focus shift to other aspects of arbitration, such as the efficiency of the enforcement process itself? As the number of international commercial disputes grows, courts may face challenges related to the speed of enforcement proceedings. Will legislative or procedural reforms be necessary to ensure that the time taken for an award to become a decree is minimal, thereby fully realizing the promise of arbitration as a quick and effective dispute resolution mechanism? Furthermore, while the current legal position on public policy is well-defined, how will Indian courts navigate future challenges that may test the boundaries of “fundamental policy of Indian law,” particularly in a rapidly evolving global economic and technological landscape?

Ultimately, the jurisprudence surrounding foreign award enforcement in India reflects a maturation of its legal system, balancing sovereign interests with international obligations. The journey from the pre-arbitration era to the current streamlined framework has been a long one, marked by key judicial interventions that have progressively simplified the process and enhanced its certainty. This evolution sends a strong signal to the global community that a foreign arbitral award in India is not merely a paper victory but a valuable legal instrument backed by a predictable and reliable enforcement mechanism. It is this certainty that will continue to make India an attractive hub for global business and a trusted partner in international dispute resolution.

Citations

- The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act,1996

- Furest Day Lawson Ltd. v. Jindal Exports Ltd. (MANU/DE/0141/1999

- Government of India v. Vedanta Limited (2020) 10 SCC 1

- Glencore Grain Rotterdam B.V. v. Shivnath Rai Harnarain (India) Co. (2008) SCC OnLine Del 1271

- Renusagar Power Co. Ltd. v. General Electric Co.1994 AIR 860

- Avitel Post Studioz Limited & Ors. v. HSBC PI Holdings (Mauritius) Limited(2024 INSC 242)

- Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading S.A. and Anr. (2002) 4 SCC 105

- Balco v. Kaiser Aluminium Technical Services Inc. (2012) 9 SCC 552

- Roger Shashoua and others v. Mukesh Sharma and others (2017) 14 SCC 722

- National Aluminum Co. Ltd. v. Pressteel & Fabrications (P) Ltd. & Anr.(2004)1 SCC 540

- AFCONS Infrastructure Ltd. v. The Board of Trustees of the Port of Mumbai (MANU/MH/1398/2013)

- Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015

- Batliboi Enviornmental Engineers v. Hindustan Petroleum Corpn. Ltd. & Ors. (MANU/SC/1043/2023)

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit