Introduction

In a remarkable assertion of its operational success, the ED1, India’s premier financial crime-fighting agency, recently claimed a staggering conviction rate of over 94% under the stringent PMLA2. This emphatic declaration, made during the 32nd quarterly conference of zonal officers in Srinagar on Monday, September 15, 2025, stated that the agency had secured convictions in 50 of the 53 cases decided by special PMLA courts, an achievement they believe underscores their effectiveness. Furthermore, the ED highlighted its role in facilitating the restitution of assets worth over ₹34,000 crore to victims. The conference itself, held in Jammu & Kashmir, was noted in an official release as a deliberate move to “restore confidence in the security environment” of the region.

The agency’s internal focus, as discussed at the conference, is now squarely on fast-tracking cases, with the Director instructing zonal heads to expedite investigations and prosecution complaints. They even noted sending letters to registrars of all Chief Justices to consider the establishment of exclusive PMLA courts, following observations from the Supreme Court. Yet, amid this narrative of success and future streamlining, a parallel story is unfolding in the nation’s highest judicial corridors—one of deep institutional concern and a stark statistical contradiction.

How Does a 94% Conviction Rate Reconcile with the Government’s Own Judicial Data?

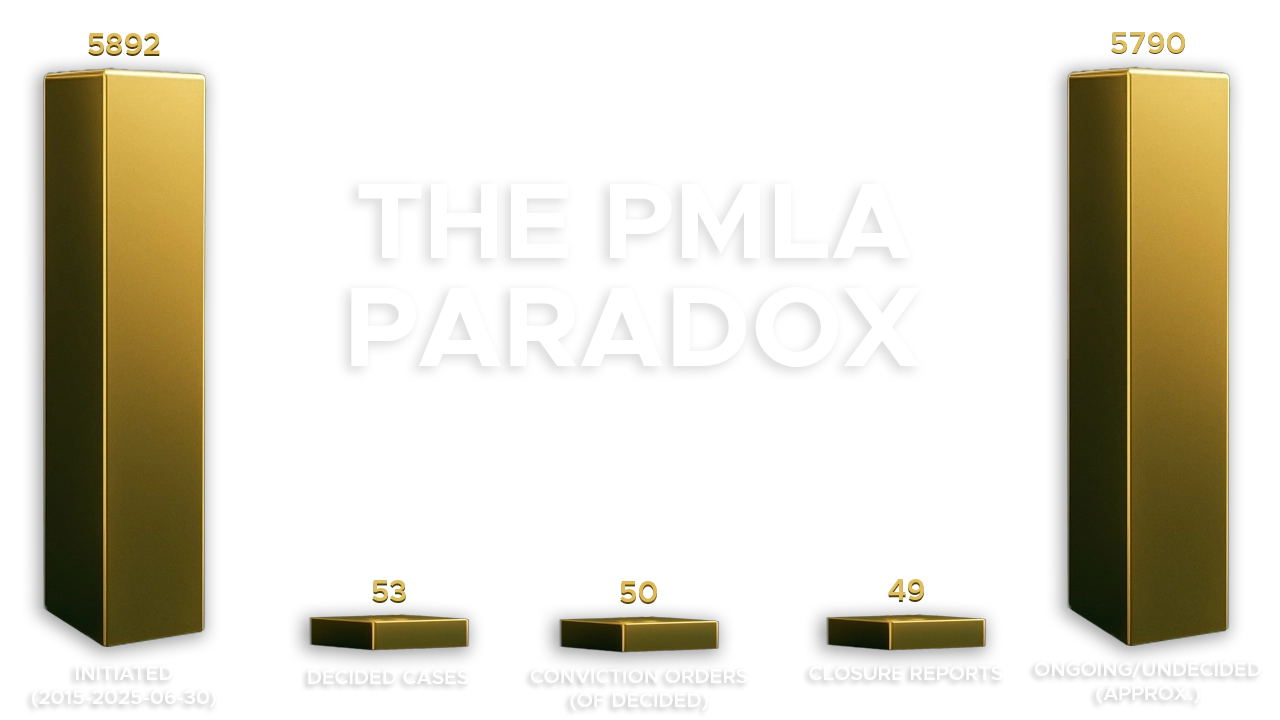

This proclaimed success by the ED presents a profound statistical dichotomy when juxtaposed with the data shared by the government in Parliament. Minister of State for Finance, in a written statement to the Rajya Sabha, provided the judicial record from January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2025. During this 10-and-a-half-year period, the ED initiated 5,892 cases for investigation under PMLA. However, as of June 30, 2025, the PMLA special courts had convicted a mere 15 persons in eight orders. The agency also filed closure reports in 49 cases.

If nearly 6,000 cases were investigated over the decade and only 15 individuals were ultimately convicted, where does the 94% figure emerge from?

The answer lies in how the conviction rate is calculated. While the courts and the public often calculate the conviction rate against the total number of cases investigated (50/5,892 = less than 1%), the ED’s figure of “convictions in 50 of the 53 cases” is based solely on the very small subset of cases that have actually reached a final verdict by the Special Court. This distinction is critical: the ED is calculating success based on cases decided on merits, not the total cases filed. This method may technically be statistically sound for a small group of closed cases, but it masks the overwhelming majority of cases—the thousands of pending investigations and trials—where the final verdict is yet to be delivered.

Is the PMLA Process Itself Becoming a Punishment, Irrespective of the Verdict?

The Supreme Court’s increasingly pointed observations suggest that the agency’s operational methods, particularly the prolonged nature of PMLA proceedings, are under scrutiny. This growing judicial criticism stems from the draconian nature of the PMLA itself, specifically the stringent bail conditions and the prolonged trial process that can lead to years of incarceration before a verdict is reached.

In a powerful verbal expression on August 7, 2025, a bench led by Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai articulated a deep concern: the ED has been “successful in sentencing them almost without a trial for years together,” even if the accused are not ultimately convicted. This sentiment implies that for many, the process of investigation, attachment of property, and denial of bail under PMLA is the punishment. Justice Ujjal Bhuyan highlighted this imbalance by questioning the low conviction rate directly, noting, “Out of 5000 PMLA cases, only 40 convictions in 10 years,” and urged the ED to “improve your investigation.”

This scrutiny has led to a major shift in the judicial paradigm concerning the “predicate offense”—the primary crime that gives rise to the proceeds of money laundering.

Does an Inordinate Delay in the Predicate Offense Undermine the Entire PMLA Case?

The Supreme Court appears to be moving away from treating money laundering as an absolute “standalone offense”—a core argument often used to justify continuing a PMLA probe even if the original crime’s case falters.

The recent stay order issued on July 27, 2025, in S. Srividhya & Ors. v. Assistant Director & Anr3., is a beacon of this new judicial thinking. A Supreme Court bench stayed the PMLA trial because a chargesheet in the predicate offense had not been filed for over seven years. The court’s reasoning was rooted in the “live and sustainable predicate offence” doctrine, indicating that a PMLA trial cannot be sustained indefinitely if its foundation is compromised by inordinate procedural delay.

This approach builds on previous judicial indications:In Bharathi Cement Corporation Pvt. Ltd. v. The Directorate of Enforcement4, the Telangana High Court had directed the money laundering trial to be paused until the scheduled offense was decided.

In S Martin v. Directorate of Enforcement5, the Supreme Court stayed the PMLA trial, later allowing it to proceed with the crucial condition that the PMLA judgment could not be pronounced until the predicate case was decided.

This jurisprudence signals a clear message: while the PMLA may have its own procedures, it cannot exist in a vacuum, especially when procedural fairness is egregiously violated by a delay in formally charging the core crime.

Will the Judiciary’s Intervention Compel a Systemic Shift in PMLA Enforcement?

Before the landmark judgment in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors6., a chaotic legal landscape existed, with High Courts holding conflicting views on the PMLA-predicate offense link. The Bombay High Court in Babulal Verma v. Enforcement Directorate7, for example, took a rigid view, asserting the offense was independent even if the predicate case was closed. In stark contrast, the Delhi High Court in Prakash Industries v. Directorate of Enforcement8 and the Allahabad High Court in Sushil Kumar Katiyar v. Union of India stressed an intrinsic link, suggesting a PMLA trial would not survive an acquittal in the scheduled offense. The Vijay Madanlal Choudhary judgment was meant to settle this, but the subsequent judicial stay orders show that the matter remains actively contested.

The ED’s high conviction rate, therefore, stands as a symbol of the immense power the agency wields—a power that results in convictions for a small fraction of cases that reach completion, while simultaneously drawing widespread judicial criticism for the prolonged and punitive nature of its investigative methods in the thousands of cases still under trial.

The ED’s drive to establish exclusive PMLA courts and fast-track trials is a direct response to these pressures. But the critical question remains: Will these judicial observations and stay orders truly compel a systemic change—leading to more focused, evidence-based, and timely prosecutions of predicate offenses—or will the dichotomy between the agency’s claimed success rate and the judicial reality of its enforcement continue to widen? The answer will determine whether the judiciary’s actions are a temporary check on power or the beginning of a new, more balanced era of justice under a powerful, yet controversial, law.

Conclusion

The enduring takeaway from this complex interplay between the Enforcement Directorate’s claims and the judiciary’s critiques is a profound necessity for institutional introspection and systemic reconciliation. The ED’s high conviction rate—a figure derived from the sliver of cases that have concluded—serves as a compelling organizational metric, yet it cannot obscure the larger, more unsettling truth revealed by the thousands of pending cases and the Supreme Court’s alarm over the low overall conviction count and prolonged incarceration. The judicial interventions, epitomized by the focus on the “live and sustainable predicate offense” doctrine in cases like S. Srividhya, are not acts of resistance but a forceful judicial attempt to re-anchor a special, powerful law—the PMLA—back within the foundational principles of criminal jurisprudence and the protection of fundamental rights. The goal of combating money laundering remains paramount, but the message from the bench is clear: deterrence must be achieved not through procedural punishment, but through timely, robust, and legally sound investigations that meet constitutional standards.

Looking ahead, the long-term effects of this judicial push will likely be a forced evolution in the ED’s investigative framework. The Supreme Court’s insistence on establishing a clearer link between the PMLA and its predicate offense, alongside the administrative drive for exclusive PMLA courts, points toward a future where the agency must prioritize quality over quantity, building airtight cases that can withstand scrutiny from their inception. This necessary reconciliation between the agency’s operational expediency and the judiciary’s commitment to due process holds the key to the PMLA’s legitimacy. Should the ED embrace this challenge, leveraging its resourcefulness to not only secure convictions in a handful of decided cases but also to successfully prosecute the broader backlog, it can transform the PMLA from a potent tool of investigation that often risks being perceived as a tool of oppression into a truly respected and effective weapon against financial crime.

Citations

- Enforcement Directorate

- Prevention of Money Laundering Act,2002

- S. Srividhya and Ors. Versus Assistant Director and Anr., Slp(Crl) No. 10113-10115/2025

- Bharathi Cement Corporation Pvt. Ltd. v. The Directorate of Enforcement Criminal Revision No. 87 of 2021

- S Martin V. Directorate of Enforcement. Slp(Crl) No. 4768/2024

- Vijay Madanlal Choudhary & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. 2023 (12) SCC 1

- Babulal Verma v. Enforcement Directorate2021 SCC OnLine Bom 392

- Prakash Industries v. Directorate of Enforcement 2022 SCC OnLine Del 2087

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit