Introduction

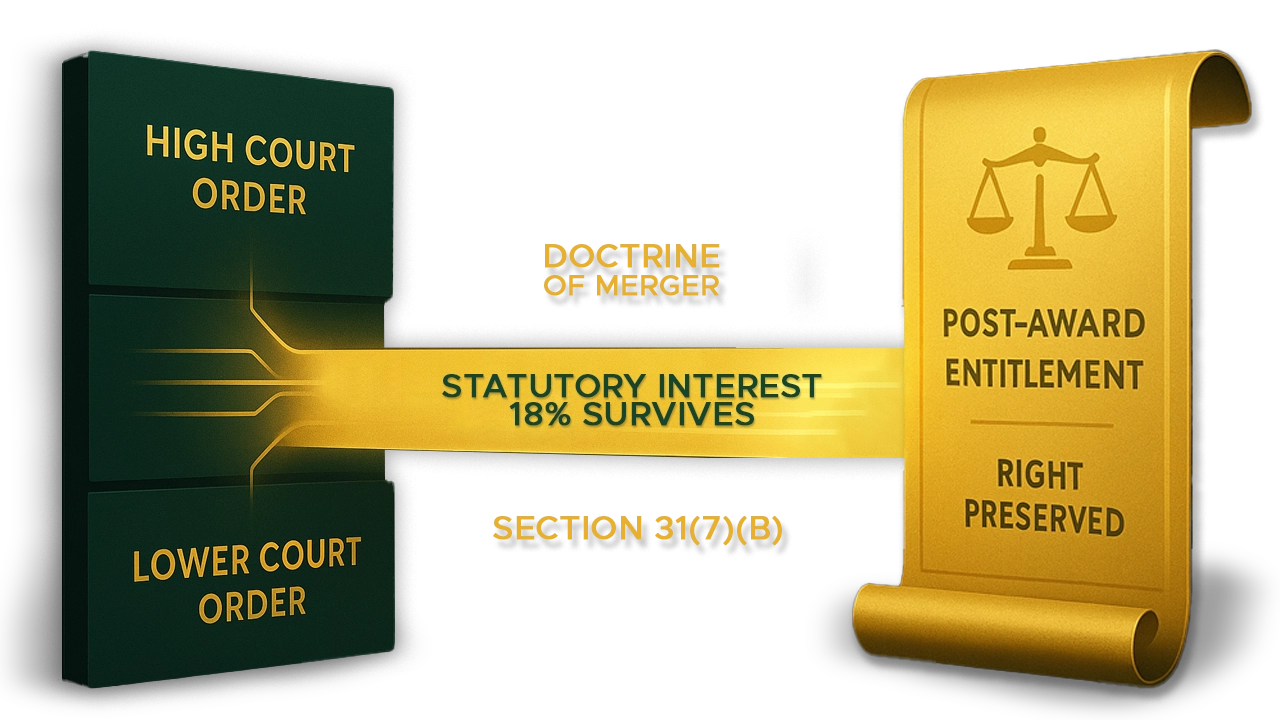

When an arbitral tribunal is silent on the rate of interest payable after the award is made, should the decree holder be deprived of the higher rate stipulated by statute? The interpretation of Section 31(7)(b) of the Arbitration Act1 often presents a complex juncture in post-award execution proceedings. In a significant pronouncement, the Gujarat High Court, through a bench led by Justice Maulik J. Shelat, recently settled this intricate question in Shah Enterprise Versus State Of Gujarat2, holding that the doctrine of merger does not preclude a decree holder from claiming post-award interest at 18% per annum under the said section, even when the award itself is silent on the matter. This ruling came in a review application stemming from a dispute involving Shah Enterprises and the State of Gujarat.

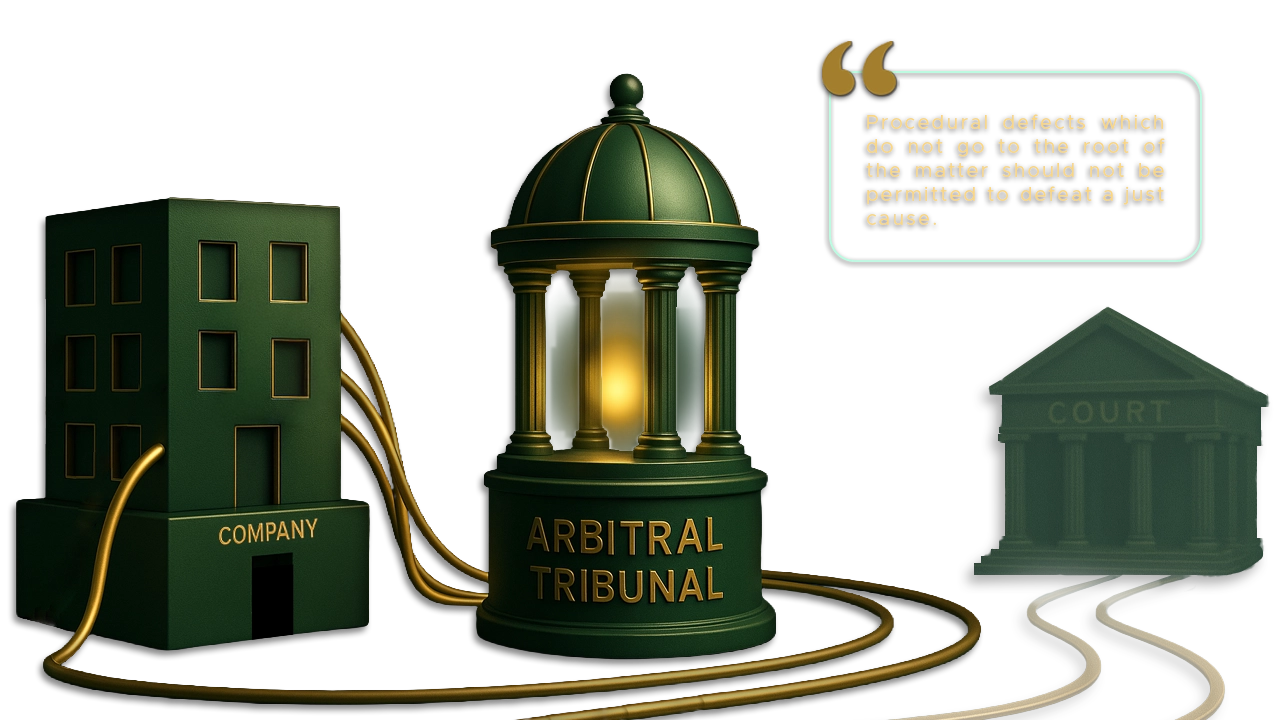

The core issue before the Court was whether the Principal District Judge correctly rejected a review application that sought to rectify an earlier order granting only 16% interest, contrary to the statutory mandate of 18%. The High Court decisively quashed the lower court’s order, asserting that an “error apparent on the face of the record” had occurred by failing to apply the correct statutory rate. This article will delve into the underlying legal principles, particularly concerning the doctrine of merger and the mandatory nature of Section 31(7)(b), which formed the basis of this crucial judgment.

The argument presented by the Learned AGP introduced a direct challenge based on the crucial legal principle known as the Doctrine of Merger. This doctrine, in its conventional application, posits that when a superior judicial forum—in an appeal or revision—modifies, reverses, or affirms a decision of a subordinate court, the lower decision merges into that of the superior forum. Consequently, the superior court’s order alone subsists, remains operative, and is the singular source of enforceability. The State’s contention, therefore, was that the Petitioner’s earlier Special Civil Application (SCA) No. 628 of 2006, which challenged the executing court’s order dated 21.10.2005, having been dismissed by the High Court, meant the original order had merged, thereby barring the Petitioner from seeking review or claiming the enhanced post-award interest of 18%mandated by Section 31(7)(b) of the Arbitration Act.

To definitively counter this position, one must first deconstruct the doctrine itself: Is merger truly a rule of universal, unyielding application? The Honourable Supreme Court, in the locus classicus case of Kunhayammed and others vs. State of Kerala and another3, provides a foundational answer, explicitly holding that the doctrine is “not a doctrine of universal or unlimited application.” Its applicability is fundamentally contingent upon two factors: the nature of the jurisdiction exercised by the superior forum and, more significantly, the content or subject-matter of challenge laid or capable of being laid before it. Merger, in essence, is determined by the issues actually adjudicated, not merely by the formal disposition of the petition.

Turning to the controversy at hand, a rigorous examination of the High Court’s earlier judgment dated 01.08.2014, dismissing the State’s SCA, revealed a dispositive fact: neither the Petitioner nor the Respondent-State had raised, questioned, or pressed into service the legality of the 21.10.2005 order in relation to the quantum of post-award interest. The earlier round of litigation, therefore, had no “occasion to decide the question in regards to the entitlement of the petitioner to receive interest at the rate of 18% after the date of the arbitral award.”

The central question thus emerges: How can a subordinate court’s decision merge into a superior court’s order if the specific, vital point of law—the claim for statutory interest—was never brought up, discussed, or answered by the superior forum? The High Court thus emphatically affirmed that for an issue that was never germane before it in the previous application and was not answered, the principle of merger would simply not arise.

Furthermore, the Court addressed the nature of the jurisdiction itself. The earlier petition was a Special Civil Application under Articles 226/227 of the Constitution. Consistent with the settled law established in Radheshyam and others vs. Chhabi Nath and others, an order passed by a Civil Court, such as the executing court, is subject primarily to the supervisory jurisdiction under Article 227. While the High Court conceded that its earlier order did bind the State regarding the award’s overall maintainability (applying the principle of merger to that narrow extent), this limited merger did not extend to every unexamined aspect of the lower court’s decree.

Since the High Court in the prior proceeding had never opined that the amount and interest ordered on 21.10.2005 were “just and appropriate,” the entire order of 21.10.2005 would not merge into the subsequent judgment of 01.08.2014 for all purposes. This meticulous disentanglement of the doctrine of merger from the factual history of the litigation allowed the High Court to conclude that the doctrine was not applicable, thereby clearing the path to correct the “error apparent on the face of the record” and rightfully grant the decree holder the mandatory 18% post-award interest under the Arbitration Act.

Conclusion

The High Court’s ruling on the non-applicability of the Doctrine of Merger in this context stands as a crucial reaffirmation of the statutory supremacy embedded in Section 31(7)(b) of the Arbitration Act. By holding that the executing court’s earlier error—in awarding only 16% interest instead of the mandatory 18%—did not merge with the subsequent dismissal of the writ petition, the judgment champions the principle that an oversight concerning a clear statutory provision cannot be protected under the garb of judicial finality, particularly when the issue was never substantively adjudicated by the superior forum. This decision ensures that the letter and spirit of the Arbitration Act, which mandates a higher compensatory interest rate post-award to discourage recalcitrant judgment debtors, are preserved, reinforcing the efficacy of the arbitral mechanism itself.

Looking forward, this judgment has significant future ramifications for the execution of arbitral awards across the jurisdiction. It establishes a strong precedent preventing government agencies and other award-debtors from successfully pleading the doctrine of merger to evade statutory liabilities regarding post-award interest. Practically, it empowers decree holders to seek rectification of errors that are apparent on the face of the record in execution proceedings, even if peripheral challenges to the underlying execution order were previously dismissed, provided the specific legal point was left unexamined. This clarifies the boundaries of the merger doctrine, limiting its application to the precise content and subject-matter of the superior court’s jurisdiction, thereby streamlining the process of enforcing full statutory entitlements.

Despite its clarity, the judgment may pose several questions for future jurisprudence to address. For instance, future disputes may arise concerning the precise definition of an “error apparent on the face of the record” in the context of arbitration execution proceedings. Furthermore, courts may need to definitively address: “To what extent does a partial challenge to an execution order limit the scope of subsequent review on an unadjudicated issue?” and “Would the doctrine of merger apply if the superior court, though not explicitly asked about the interest rate, had passed a general affirming order that was capable of including a review of all statutory compliances?” Ultimately, this ruling will serve as a foundational step toward ensuring robust protection for award holders seeking the full financial benefits guaranteed by the Arbitration Act.

Citations

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

- Shah Enterprise Versus State Of Gujarat Special Civil Application No. 18521 Of 2017

- Radheshaym and others vs. Chhabi Nath and others, reported in (2015) 5 SCC

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit