Introduction

The law focuses on the right to housing in the modern era, reaffirming its status as a fundamental right. The intersection of housing rights enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution1 and insolvency law has created a legal conundrum with seismic implications. This was the primary holding of the Supreme Court of India in Mansi Brar Fernandes versus Shubha Sharma and Anr2. with resolving the issue of whether an allottee of a residential unit qualifies as a ‘financial creditor’ under the IBC3 or is merely a ‘speculative investor’ using the Code as a debt recovery tool.

The Bench, comprising Justice J.B. Pardiwala and Justice R. Mahadevan, held that a genuine homebuyer, intending to take physical possession, is a financial creditor, while a speculative investor, driven solely by profit through mechanisms like assured returns or compulsory buy-back clauses, is not and has alternate remedies. It further urged the Union Government to establish a revival fund for stressed real estate projects and asserted that the State cannot remain a ‘silent spectator’ but must fulfill its constitutional duty to safeguard homebuyers.

The petitioner entered in a MoU4 with the Corporate Debtor, Gayatri Infra Planner Private Limited. The MoU included a buy-back clause at the Corporate Debtor’s discretion for decided sum, or possession if the option was not exercised. Neither possession nor payment was made, and post-dated cheques were dishonored, leading the petitioner to file a Section 7 IBC petition, which the NCLT admitted but the NCLAT subsequently reversed, labeling her a “speculative investor.”

The Appellant argued that they are bona fide homebuyers and financial creditors under Section 5(8)(f) of the IBC, as their investment carried the ‘commercial effect of borrowing’ and ‘time value of money.’ They asserted that the mere presence of a buy-back clause, particularly one at the Corporate Debtor’s discretion, does not automatically establish speculative intent, especially since the allottee was always willing to accept possession. The core issue, they contended, was the builder’s default and not the allottee’s intention.

The Respondent countered that the transactions were purely speculative, structured primarily for abnormal financial returns, and not for acquiring a residential property for personal use. They argued that the Appellants’ reliance on post-dated cheques, Section 138 of NI Act5 proceedings, and the absence of a genuine interest in monitoring construction or obtaining possession clearly demonstrated their status as speculative investors misusing the IBC, which is not a recovery mechanism for mere investment contracts.

The IBC Line: Distinguishing ‘Homebuyer’ from ‘Speculator’ in Real Estate Insolvency

The Supreme Court, in its analysis, relied on key precedents to draw the critical distinction between a genuine homebuyer and a speculative investor. In Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Ltd. v. Union of India6 This was used to underscore that while genuine homebuyers deserve protection, the IBC cannot be misused by speculative investors seeking premature exits or recovery of returns. The Court emphasized that such speculative participants have alternate remedies under consumer protection laws, RERA, or civil courts.

In another case Jute Investment Co. Ltd. v. CIT7, general interpretive principle was applied to hold that schemes with “assured returns, compulsory buybacks, or excessive exit options are in reality ‘finality derivatives masquerading as housing contracts.'” The Court looked beyond the nomenclature to the transaction’s true nature.

The Supreme Court in the case of Samatha v. State of A.P8. set the precedent that grounded the discussion in constitutional law, reiterating that the right to housing is a fundamental right under Article 21. This elevated the State’s constitutional obligation to safeguard homebuyers and confirmed that home-buying is not a mere commercial transaction.

The Court resolved the dichotomy by adopting a test of intent—whether the allottee’s primary purpose was to obtain physical possession of the residential unit for use (a genuine homebuyer) or to generate profits through a financial instrument disguised as a real estate transaction (a speculative investor).

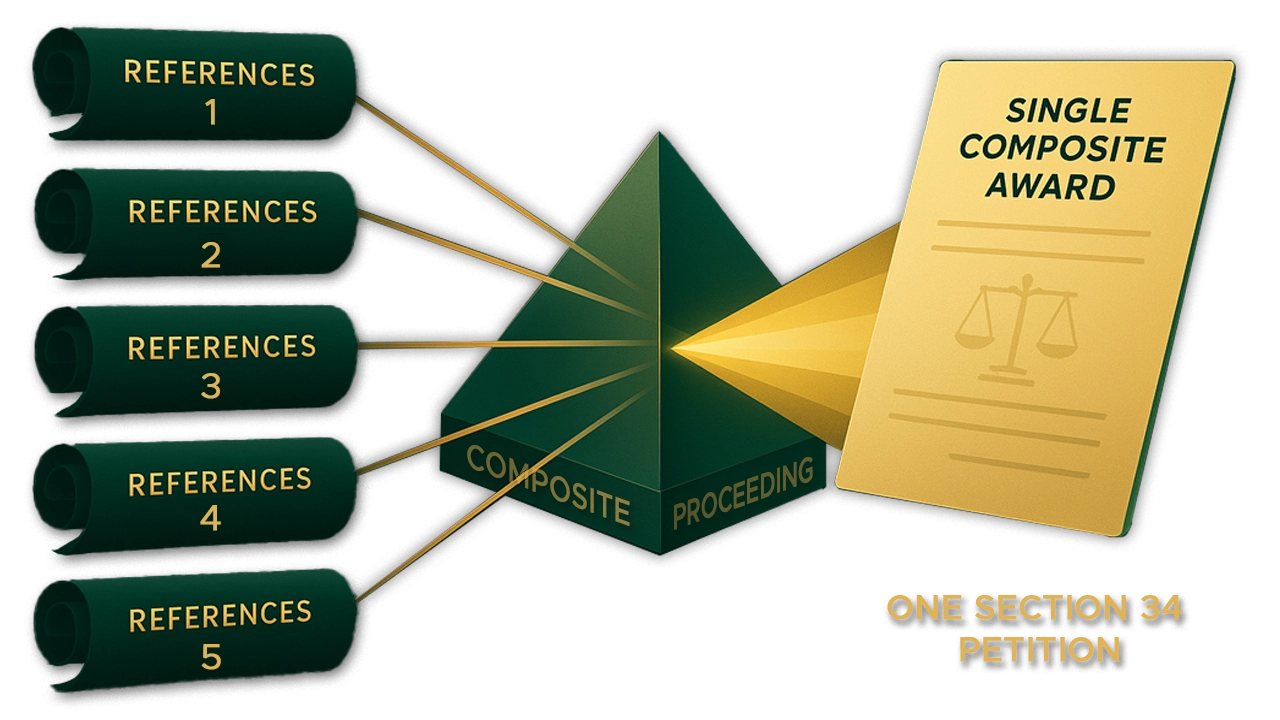

The Court clarified that the existence of a buy-back or assured return clause is a strong indicator of speculative intent, especially when the returns are exorbitant and the allottee demonstrates no interest in the project’s physical progress. By framing the issue as one of constitutional duty to safeguard the fundamental Right to Shelter for genuine buyers, the court removed the dichotomy. The determination, the court held, is a factual inquiry guided by factors like the nature of the contract, the number of units purchased, and the presence of assured returns. The Court upheld the NCLAT’s decision, confirming that the appellants were speculative investors and therefore not entitled to initiate Section 7 proceedings under the IBC.

Crucially, the court issued several affirmative directions to protect genuine homebuyers and strengthen the real estate ecosystem. It directed that every residential real estate transaction for new housing projects shall be registered with local revenue authorities upon payment of at least 20% of the property cost. It mandated that proceeds from projects at nascent stages (where land is unacquired or construction hasn’t commenced) must be placed in an escrow account and disbursed in phases as per RERA-sanctioned SOPs.

The Court further urged the Union Government to come up with a revival fund for stressed real estate projects and asserted that the government cannot remain a ‘silent spectator.’ It also directed that NCLT and NCLAT vacancies must be filled on a ‘war footing’, and dedicated IBC benches with additional strength should be constituted, utilizing retired judges on an ad hoc basis.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court in Mansi Brar Fernandes (Supra) affirmed the principle that the IBC is a tool for revival and protection, not a recovery mechanism for speculative investments. The judgment clearly distinguished a genuine homebuyer (a financial creditor under IBC, protected by the fundamental Right to Shelter under Article 21) from a speculative investor (driven by profit motives and with access to other remedies like RERA or civil courts). By establishing the ‘intent test’ focusing on the desire for physical possession versus financial return, the court solidified a critical safeguard against the misuse of the IBC to the detriment of genuine allottees and viable real estate projects.

This judgment has profound future ramifications for the Indian real estate and insolvency landscape. It is expected to significantly deter speculative investments disguised as housing contracts, especially those incorporating assured return or compulsory buy-back clauses, as such ‘investors’ now face limited recourse under the IBC. This, in turn, may lead to a cleaner, more transparent real estate market focused on genuine construction and delivery. For RERA authorities, the mandate to create Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for escrow account disbursements and the emphasis on the Model RERA agreement will likely strengthen their regulatory oversight.

Most importantly, the directive to the Union Government regarding the urgent need to fill NCLT/NCLAT vacancies and upgrade infrastructure addresses a systemic bottleneck, aiming for faster resolution of insolvency cases, which is critical for project revival and timely possession for genuine homebuyers. How will the courts treat cases where a genuine homebuyer is forced into a buy-back clause by a dominant builder as a condition of sale—a scenario where the allottee’s intent is genuine, but the contractual terms are speculative?

Citations

- The Constitution of India, 1950

- Mansi Brar Fernandes versus Shubha Sharma and Anr. Civil appeal no. 3826 of 2020

- The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016

- Memorandum of Understanding

- The Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

- Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Ltd. v. Union of India 2019 8 SCC 416

- Jute Investment Co. Ltd. v. CIT 1980 1 SCC 117

- Samatha v. State of A.P. 1997 8 SCC 191

Expositor(s): Adv. Shreya Mishra