Introduction

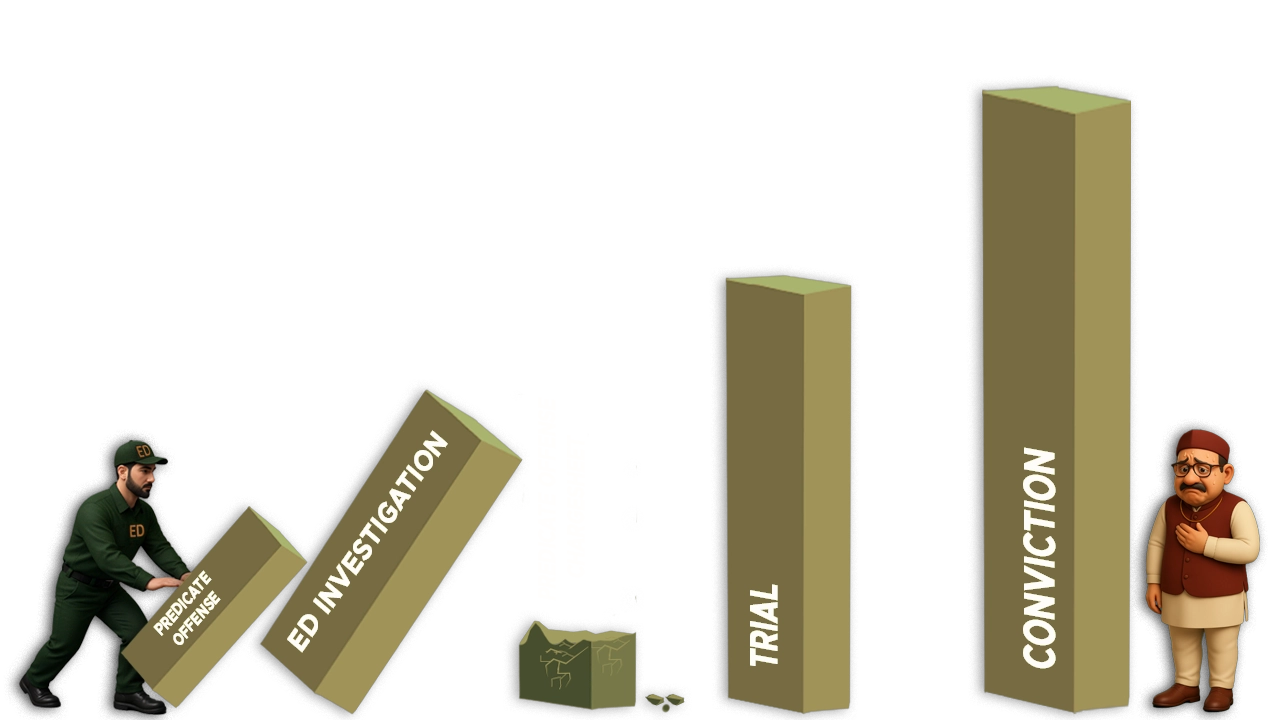

The PMLA1 is currently undergoing a significant shift in how it’s being interpreted and applied by the judiciary. The central nerve of this change is the inordinate delay in filing a chargesheet for the “predicate offense,” the very crime that gives rise to the “proceeds of crime” under the PMLA. This issue has sparked a renewed debate about the PMLA’s nature as a “standalone” offense, leading to a new wave of judicial criticism against the ED2.

The recent stay order of the Supreme Court, issued on July 27, 2025, in S. Srividhya & Ors. v. Assistant Director & Anr3., signals a renewed shift in this judicial paradigm. In this case, a bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta stayed the PMLA trial because a chargesheet in the predicate offense had not been filed for over seven years.

The court’s reasoning was rooted in the “live and sustainable predicate offence” doctrine, where it questioned the very basis of a PMLA trial when the core offense had not been formally charged. The delay was deemed “fundamental,” and the court’s action indicates a clear departure from the absolute “standalone offense” theory. This stay is a strong indication that while the PMLA might have its own procedures, it cannot exist in a vacuum, especially when procedural fairness is so severely compromised by an inordinate delay in the predicate case. The order suggests that the lack of a chargesheet for years is sufficient grounds to question the legitimacy of the PMLA trial itself.

The stay order in the S. Srividhya case, however, isn’t the first time the judiciary has considered such an approach. It can be seen as an indication towards the application of this doctrine, building upon similar considerations in earlier cases. For instance, in Bharathi Cement Corporation Pvt. Ltd. v. The Directorate of Enforcement4, the Telangana High Court had directed the money laundering trial to be paused until the special court had decided on the scheduled offense. Although this case was eventually dismissed by the Supreme Court on the ED’s prayer, it laid the groundwork for the idea that the PMLA trial’s progression could be intertwined with the predicate offense’s status. A similar indication was seen in S Martin v. Directorate of Enforcement5, where the Supreme Court initially stayed the PMLA trial of lottery tycoon Santiago Martin, though it later allowed both trials to proceed with the condition that the PMLA judgment wouldn’t be pronounced until the CBI’s predicate Case was decided. These cases, taken together, suggest a consistent judicial thought process that the PMLA trial, in certain circumstances, cannot be treated in complete isolation from its foundational offense.

The Predicate Offense Problem: Diverging Views Before Vijay Madanlal

Before the landmark Supreme Court judgment in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors6., there was a lack of clarity and conflicting opinions among High Courts regarding the relationship between the PMLA and the predicate offense. This judicial divergence created a legal landscape where the fate of an accused person could vary significantly depending on the court.

For example, the Hon’ble High Court of Bombay in Babulal Verma v. Enforcement Directorate7 took a rigid view, holding that the offense of money laundering was independent of the scheduled offense. According to this view, even if a closure report was filed and accepted in the predicate offense, the ED’s investigation under the PMLA could continue. This perspective treated the PMLA as a completely separate and self-contained law.

In stark contrast, other High Courts emphasized the intrinsic link between the two offenses. The Hon’ble High Court of Delhi in Prakash Industries v. Directorate of Enforcement8 stressed that a prerequisite relation existed between the commission of a scheduled offense and the subsequent act of money laundering. Similarly, the Hon’ble High Court of Allahabad in Sushil Kumar Katiyar v. Union of India9 held that a PMLA trial would not survive after the acquittal of a person from the scheduled offense. Yet, a few Directorate of Enforcement v. Gagandeep Singh other courts, like the Hon’ble High Court of Karnataka in K. Sowbhagya v. Union of India10 and the Hon’ble High Court of Madras in VGN Developers P. Ltd. v. The Deputy Director, Directorate of Enforcement11, further muddled the waters by treating money laundering as a “standalone offence,” with the former even extending the definition of “proceeds of crime” to property used in a scheduled offense.

Broader Criticisms and Future Implications

But the criticism from the judiciary doesn’t stop at just the chargesheet issue. It extends to the very essence of the ED’s operational methods. In a recent hearing on August 7, a bench led by CJI B.R. Gavai verbally expressed a deep concern that the ED has been “successful in sentencing them almost without a trial for years together12,” even if the accused are not ultimately convicted. This powerful statement echoes the sentiment that for many, the PMLA process—with its stringent bail conditions and prolonged incarceration—is the punishment itself, regardless of the final verdict.

The courts are also questioning the ED’s abysmal conviction rate. “What is the conviction rate so far in ED matters?”13 the CJI asked the Solicitor General. This question highlights a fundamental imbalance: why are thousands of cases being filed if only a handful lead to convictions? As the Supreme Court has noted in another context, “Out of 5000 PMLA cases, only 40 convictions in 10 years14.” This glaring statistic has prompted judges to ask the ED to “improve your investigation” and ensure that the law is not being used to keep people as undertrials for years. In essence, judges are sending a clear message: while the ED’s goal of combating financial crime is laudable, its methods must remain within the “four corners of the law.” The judiciary is no longer just a passive spectator; it is an active participant in shaping how this powerful law is applied, ensuring that the quest for justice does not become a tool for injustice.

Conclusion

The legal takeaways from this evolving jurisprudence are profound. The judiciary is firmly establishing a new precedent where the principle of a “live and sustainable predicate offense” is paramount. The stay order in S. Srividhya & Ors. v. Assistant Director & Anr. is not an isolated incident but a beacon, signaling that inordinate delays in the predicate chargesheet will no longer be tolerated. It indicates a move away from the “standalone offense” argument, at least in cases where procedural fairness is so egregiously violated. This new judicial approach provides a glimmer of hope for individuals caught in the protracted and often punitive process of a PMLA trial. It sets a new benchmark for investigative agencies, forcing them to build a robust case from the ground up, rather than using the PMLA as a shortcut to bypass standard criminal procedures. The future implications are clear: the ED will be held to a higher standard of accountability and will be compelled to expedite its investigations into predicate offenses.

This shift begs a critical question for the future: Will these judicial observations and stay orders compel a systemic change within the investigative agencies, leading to more focused and timely prosecutions? Or will this remain a case-by-case battle, leaving the broader issues of low conviction rates and procedural delays to fester? The answers to these questions will determine whether the judiciary’s recent actions are a temporary check on power or the beginning of a new, more balanced era of justice under the PMLA.

Citations

- Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002

- Enforcement Directorate

- S. Srividhya and Ors. Versus Assistant Director and Anr., Slp(Crl) No. 10113-10115/2025

- Bharathi Cement Corporation Pvt. Ltd. v. The Directorate of Enforcement Criminal Revision No. 87 of 2021

- S Martin V. Directorate of Enforcement. Slp(Crl) No. 4768/2024

- Vijay Madanlal Choudhary & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. 2023 (12) SCC 1

- Babulal Verma v. Enforcement Directorate2021 SCC OnLine Bom 392

- Prakash Industries v. Directorate of Enforcement 2022 SCC OnLine Del 2087.

- Sushil Kumar Katiyar v. Union of India 2016 SCC OnLine All 2632

- K. Sowbhagya v. Union of India 2016 SCC OnLine Kar 282

- VGN Developers P. Ltd. v. The Deputy Director, Directorate of Enforcement 2019 SCC OnLine Mad 13270

- Kalyani Transco vs M/s Bhushan Steel and Power Ltd and connected appeals C.A. No. 1808/2020

- Partha Chatterjee Vs Directorate of Enforcement Slp(Crl) No. 13870/2024

- Sunil Kumar Agrawal Versus Directorate of Enforcement, Slp(Crl) No. 5890/2024

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit