Introduction

In the complex theater of international taxation, does a formal certificate of residence provide an absolute shield against domestic tax scrutiny, or can the “head and brain” of an entity be traced to another jurisdiction to uncover tax avoidance? This question sat at the heart of the landmark dispute in The Authority for Advance Rulings (Income Tax) & Ors v. Tiger Global International II Holdings (2026)1. This case challenged the long-held sanctity of the “Mauritius Route” in the face of modern anti-abuse frameworks, placing the Indian Revenue and the Tiger Global group at the center of a fundamental debate over treaty entitlement.

The primary respondents in this matter were Tiger Global International II, III, and IV Holdings, incorporated under the laws of Mauritius and established as holding entities. While they claimed to be managed by a local Board of Directors, they were part of a larger web of entities ultimately belonging to Tiger Global Management LLC (TGM), based in the United States. The appellant, the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR), along with the Indian Income Tax Department, contended that these Mauritian entities were merely “see-through” conduit companies created to exploit the India-Mauritius Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA).

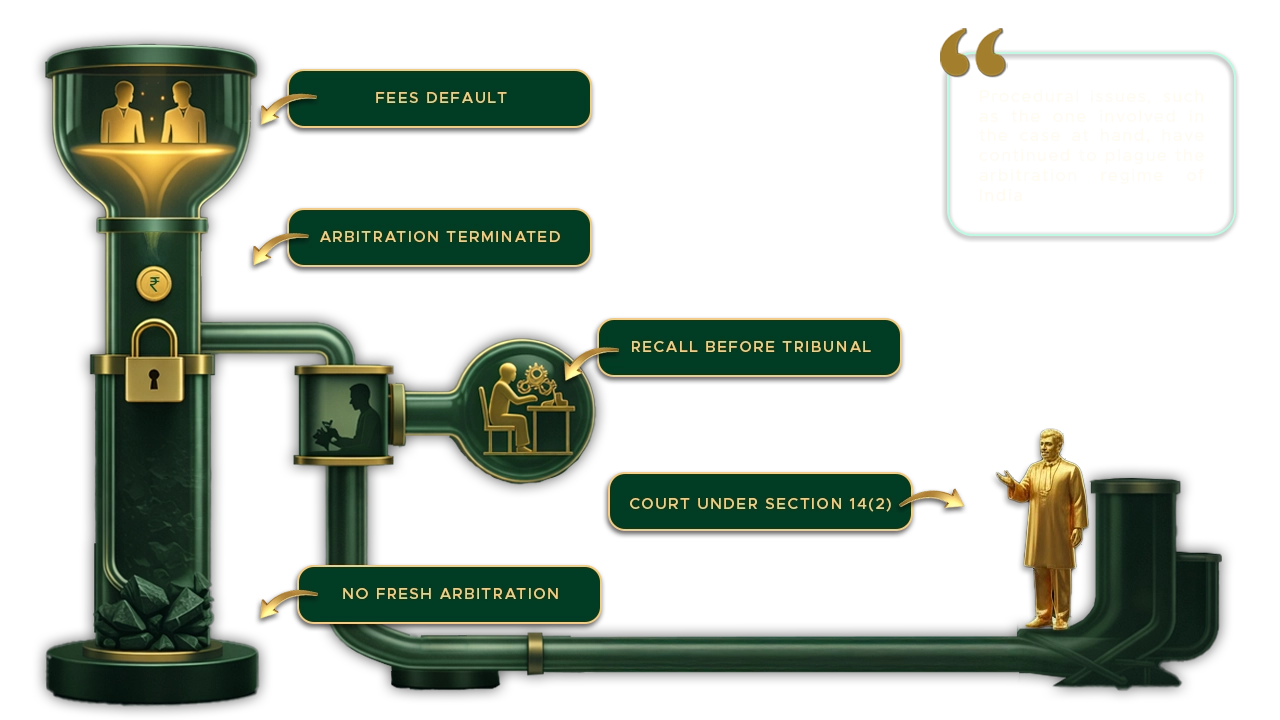

The dispute arose from a multi-billion-dollar global transaction where Tiger Global International (hereinafter referred to as the assessee) sold its shares in Flipkart Private Limited, a Singapore-based company, to Fit Holdings S.A.R.L. (a Luxembourg entity) as part of Walmart Inc.’s majority acquisition of Flipkart. Although the sold entity was Singaporean, it derived its substantial value from assets and operations located in India. Seeking certainty on their tax liability, the Tiger Global entities approached the AAR to rule whether the capital gains from this sale were exempt under the India-Mauritius DTAA. The AAR, however, rejected the applications, finding that the entire structure was a “preordained arrangement” designed for tax avoidance. Furthermore, when the assessee approached the Assessing Officer to obtain a “Nil Rate Certificate,” the request was rejected due to the evasive intent of the transaction, and a lower rate was approved by the AO. While the Delhi High Court later quashed this rejection, favoring the assessees, the matter finally reached the Supreme Court of India.

Legal Contentions: Form vs. Substance

The legal battle centered on a classic tug-of-war between the “substance over form” doctrine and the sanctity of treaty-based tax benefits. The Revenue argued that the respondents were merely shell entities, asserting that the true “head and brain” of the operations resided in the USA rather than Mauritius. They pointed to the fact that high-value financial decisions, specifically those exceeding USD 250,000 were controlled by a US resident. Furthermore, the Revenue invoked the “look-through” principle under Section 9(1) of the Income Tax Act2, claiming that because the value of the Singaporean shares was ultimately derived from Indian assets, the gains should be taxable in India regardless of the intermediary structures. They maintained that a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) serves only as prima facie evidence and should not act as a shield to prevent authorities from investigating the actual commercial substance of a transaction.

In response, the Assessees anchored their defense in established judicial precedents, such as Azadi Bachao Andolan and Vodafone, arguing that a TRC issued by Mauritian authorities must be treated as conclusive evidence of residence and beneficial ownership. They vehemently rejected the “conduit” label, highlighting their role as legitimate pooling vehicles representing over 500 investors across 30 different jurisdictions. To solidify their position, they invoked the principle of grandfathering, asserting that because their investments were made prior to April 1, 2017, they were legally protected from the General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR) and any subsequent amendments to treaty protocols.

Interplay of Tax Certificates and GAAR

The TRC is No Longer an Absolute Shield: The Court clarified that while Section 90(4)3 makes a TRC an “eligibility condition,” it does not state that it is “sufficient” evidence to preclude an inquiry into tax avoidance. The Court noted that statutory amendments, including the introduction of Section 90(2A)4, now empower the Revenue to look behind the certificate if an entity is found to be a device for tax avoidance.

The Primacy of GAAR: The ruling emphasized that GAAR (General Anti-Avoidance Rule), under Chapter X-A, operates as an “overreaching anti-abuse regime”. Even if a treaty (DTAA) provides benefits, Section 90(2A) ensures that GAAR can override these benefits if the arrangement lacks commercial substance. The Court found that because the actual transfer of investments occurred in May 2018 (after the April 2017 cut-off), the GAAR provisions were squarely applicable.

The Court revisited its own landmark rulings to refine their application:

Union of India v. Azadi Bachao Andolan5: Previously used to argue that “treaty shopping” was permissible, the Court now held that this 2004 ruling must be read in the context of the new statutory anti-abuse framework that did not exist at that time.

McDowell & Co. Ltd. v. CTO6: This established the “Judicial Anti-Avoidance Rule” (JAAR), asserting that tax planning must be within the framework of the law and not colorable devices.

Vodafone International Holdings BV v. UOI7: While Vodafone protected legitimate business structures, it also affirmed that the Department is entitled to “pierce the corporate veil” if a company is interposed as a mere device to evade tax.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court ultimately set aside the High Court’s judgment, ruling that the Tiger Global entities failed the “substance” test. By identifying that the real control rested with US-based individuals and that the Mauritian entities lacked independent decision-making autonomy for significant transactions, the Court concluded these were “see-through” entities. This ruling serves as a stark reminder to global investors: in the modern era of GAAR, the “spirit” of the law and the “substance” of the entity will always prevail over the “form” of a residency certificate.

Citations

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla, Srijan Sahay(Intern), Devansh Gautam(Intern)