Introduction

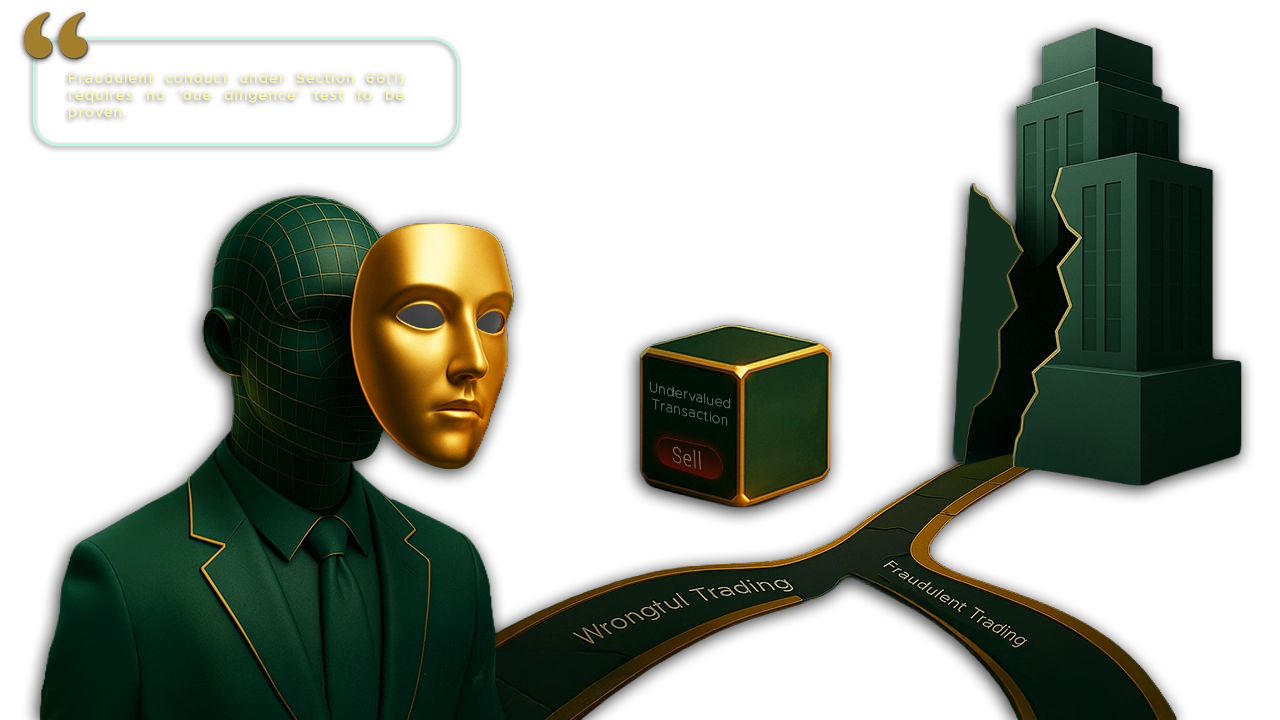

The pursuit of a “paper decree” often leads judgment creditors into a labyrinth of enforcement challenges, where the lines between corporate entities and personal liability become a battleground for commercial recovery. In the modern era, the legal focus has shifted toward ensuring that arbitral awards are not rendered hollow by strategic asset shielding, yet the sanctity of the “Executing Court” remains bound by the rigid perimeters of the decree itself.

This critical tension was the centerpiece of Manjeet Singh T. Anand v. Nishant Enterprises HUF1 & Anr2., heard by the High Court of Judicature at Bombay, presided over by Justice R.I. Chagla. The court primarily held that an executing court cannot go “behind or beyond” an award to fix personal liability on a Karta for the principal debts of an HUF if the award specifically declined such a personal relief, while also addressing the complex interplay of territorial jurisdiction in the execution of deemed decrees.

The Applicant sought to enforce an Arbitral Award of certain sum against an HUF (Respondent No.1) and its Karta (Respondent No.2). While the Award was passed, the Respondents challenged it under Section 34 of Arbitration Act3, obtaining a stay only on the “costs” component, leaving the principal sum outstanding. The Applicant alleged that the Respondents were siphoning assets to defeat the Award and sought recourse against the Karta’s personal assets, despite the Karta claiming that his personal property was immune from the HUF’s specific decretal debt.

The Karta’s Shield: Adhering to the Decree in Execution

The Respondents raised a two-pronged preliminary objection: first, that the Bombay High Court lacked territorial jurisdiction under Sections 38 and 39 of the CPC4 because the HUF’s assets were located in Thane, not Mumbai. Second, Respondent No.2 (the Karta) contended that the Arbitral Tribunal had expressly awarded the principal sum only against the HUF and not against him personally, thereby making his personal assets unavailable for execution based on the principles of res judicata and the limitations of an executing court.

The Applicant argued that since the arbitration was seated in Mumbai, the Court had jurisdiction under Section 2(1)(e) of the Arbitration Act. Regarding the Karta’s liability, the Applicant maintained that an HUF is not a separate legal entity like a company but a family collective, making the Karta personally liable for the unsatisfied debts of the HUF, especially when assets were being dissipated.

The Court meticulously analyzed the limits of its power by citing the Supreme Court’s ruling in Sundaram Finance Ltd. vs. Abdul Samad & Anr5, which clarified that an award can be executed by any court where the assets are located, stating:

“The enforcement of an award through its enforcement can be filed anywhere in the country where such decree can be executed and there is no requirement for obtaining a transfer of the decree.”

On the issue of personal liability, the court looked at Vikram Anilkumar Patel vs. Pravinchandra Jinabhai Patel6, emphasizing that under Section 47 of the CPC.

“The Executing Court has no right to vary the terms of the decree… It cannot add or alter the decree and cannot add relief not granted by the decree.”

Analysis of these precedents confirmed that because the Sole Arbitrator specifically awarded the principal sum against the HUF alone despite a prayer for “joint and several” liability the omission constituted a deemed refusal of personal liability against the Karta under Explanation V of Section 11 of the CPC.

The Court removed the dichotomy between the “corporate personality” of an HUF and the personal liability of its Karta by strictly adhering to the “inspection hole” theory of execution. Justice Chagla observed that while a Karta traditionally manages HUF affairs, the Arbitrator’s decision to limit the money award to the HUF’s assets was a final adjudication. By hearing both sides, the Court determined that it could not “rewrite” the Award during execution to include the Karta’s personal property, as doing so would violate the principle that an executing court cannot travel behind the judgment. On jurisdiction, the court reconciled the “deemed decree” status by holding that once the “umbilical cord” with the arbitral seat is snapped, execution must follow the CPC’s rules regarding the location of assets.

Conclusion

The ruling in the Manjeet Singh T. Anand (Supra) case reinforces the critical distinction between the adjudication of a debt and its subsequent enforcement. It serves as a stern reminder to decree holders that the wording of an Arbitral Award is definitive; if a specific liability is not carved out during the arbitration, it cannot be “resurrected” through the backdoor of execution proceedings.

The future ramifications of this judgment are significant for the Indian arbitration landscape. It provides a shield for individuals against “execution overreach” and mandates that claimants must be extremely precise in seeking “joint and several” reliefs during the merits stage. Furthermore, it clarifies that the seat of arbitration does not grant an automatic “home court advantage” for execution if the assets of the debtor are located elsewhere, potentially decentralizing execution filings across various districts.

Will courts allow the “piercing of the HUF veil” if clear evidence of fraudulent siphoning is presented during execution? Should the Arbitration Act be amended to provide clearer procedural guidelines for the execution of awards against non-signatories or family managers? It is suggested that parties in arbitration should seek specific “findings of personal liability” at the interim stage under Section 17 to ensure that the final award remains robust and enforceable against all potential asset pools.

Citations

Expositor(s): Adv. Shreya Mishra