Introduction

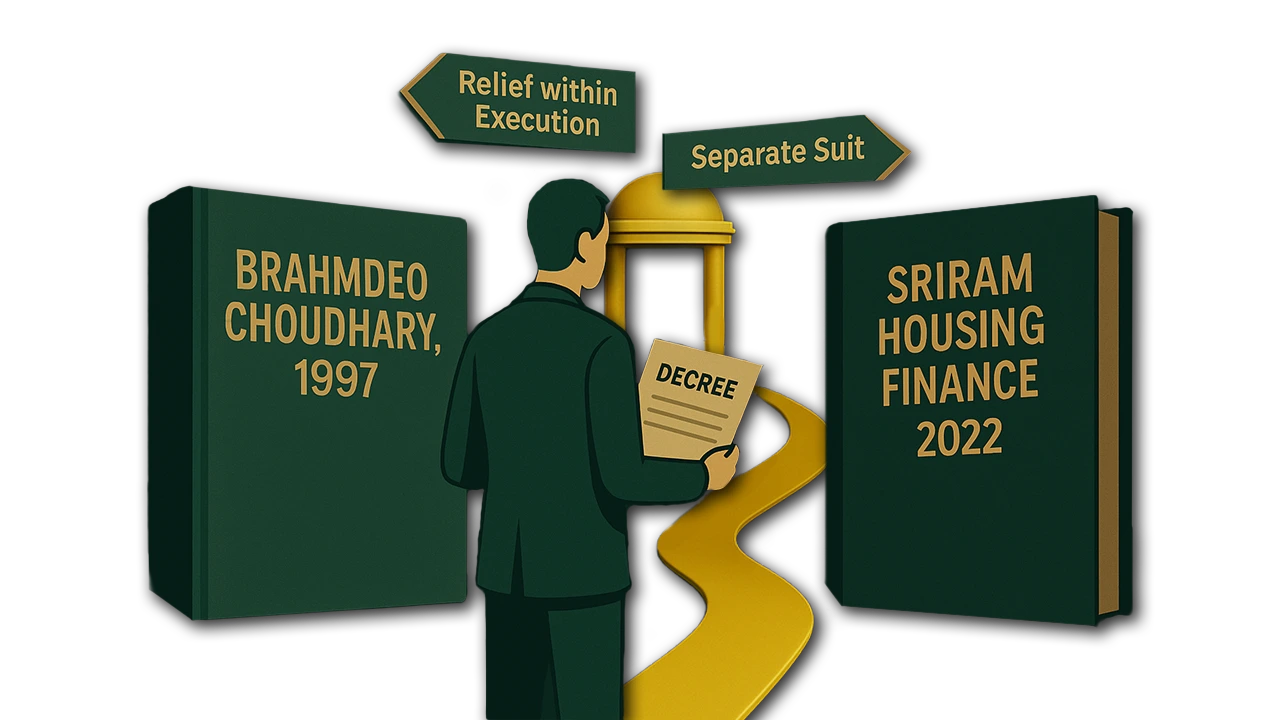

The Supreme Court of India finds itself at a crucial juncture, tasked with resolving a significant judicial inconsistency that impacts the enforcement of civil decrees. The core of the matter lies in the divergent interpretations of Order XXI Rule 97 of CPC1, a provision designed to address resistance or obstruction during the execution of a decree. This conflict, brought to the fore in the recent plea of P. Sumathi v. K. Krishna Gounder & Ors.2, pits two previous Supreme Court rulings against each other: Brahmdeo Choudhary v. Rishikesh Prasad Jaiswal3 (1997) and Sriram Housing Finance v. Omesh Misra Memorial Charitable Trust4 (2022). The outcome of this deliberation will undoubtedly clarify the procedural landscape for both decree-holders and third parties in execution proceedings.

The Conundrum: Who Can Invoke Order XXI Rule 97 CPC?

At the heart of the current legal debate is a fundamental question: Who possesses the legal standing to seek relief under Order XXI Rule 97 CPC when faced with resistance or obstruction to the execution of a decree? This seemingly straightforward query has led to two distinct and conflicting interpretations by the Supreme Court itself, creating uncertainty and inconsistency in the lower courts.

The P. Sumathi case, which recently prompted the Supreme Court to issue a notice, perfectly encapsulates this judicial quandary. The Madras High Court had, relying on the Sriram Housing Finance precedent, dismissed the petitioner’s execution application, holding that as a third party, she was not entitled to invoke provisions intended solely for decree-holders or judgment-debtors. This decision directly contradicted the petitioner’s reliance on Brahmdeo Choudhary, which had expanded the scope of Order XXI Rule 97 to even permit a third party to seek relief against dispossession.

To fully grasp the implications of this conflict, let us delve into a depth analysis of both judgments.

Brahmdeo Choudhary v. Rishikesh Prasad Jaiswal (1997): Broadening the Horizon of Justice

In Brahmdeo Choudhary v. Rishikesh Prasad Jaiswal, the Supreme Court was presented with a scenario where a decree-holder sought possession of immovable property. What happens when someone, not a party to the original decree, obstructs this process? Does the law offer recourse to such an obstructionist even before they are dispossessed?

The Court in Brahmdeo Choudhary emphatically held that under Rule 35 of Order XXI CPC, a warrant for possession can be sought against persons occupying immovable property, provided they are judgment-debtors or persons claiming through them. However, a critical distinction was drawn: what if resistance is offered by a purported stranger to the decree? The Court clarified that the decree-holder cannot simply bypass such obstruction and insist on reissuance of a warrant for possession with police force under Order XXI Rule 35. This, the Court reasoned, would circumvent the procedure laid down under Order XXI Rule 97 for removing obstruction by strangers.

The judgment further elucidated a crucial point: once such an obstruction is noted by the executing court, can the court simply tell the obstructionist to first lose possession and then seek remedy under Order XXI Rule 99 CPC for restoration of possession? The Brahmdeo Choudhary court firmly rejected this notion. It held that the resistance and/or obstruction to possession of immovable property as contemplated by Order XXI Rule 97 CPC could be offered by “any person.” The words “any person” were deemed comprehensive enough to include not just judgment-debtors or those claiming through them, but even persons claiming independently and who would, therefore, be total strangers to the decree.

The rationale behind this expansive interpretation was rooted in principles of natural justice and avoiding irreparable injury. The Court emphasized that if a stranger to the decree, alleging independent right, title, and interest in the decretal property, makes a timely grievance before the execution warrant is actually executed, they should not be summarily dismissed. Their grievance, the Court stressed, should be heard on merits. To hold otherwise would condemn such an obstructionist totally unheard, leading to a patent breach of natural justice.

The Brahmdeo Choudhary judgment, therefore, established that when a decree-holder complains about resistance or obstruction offered by any person, a “lis” arises between the decree-holder and the obstructionist. This “lis” must be adjudicated upon as enjoined by Order XXI Rule 97, sub-rule (2), and the subsequent rules of Order XXI. This adjudication, covering questions relating to right, title, and interest in the property, would be treated as a decree under Order XXI Rule 101, making it appealable, and importantly, barring a separate suit. The Court saw the gamut laid down by Order XXI Rules 97 to 103 as a complete code, providing the sole remedy for the parties concerned to have their grievances finally resolved in execution proceedings themselves.

Sriram Housing Finance v. Omesh Misra Memorial Charitable Trust (2022): A Literal and Narrower Reading

In stark contrast to the expansive interpretation adopted in Brahmdeo Choudhary, the Supreme Court in Sriram Housing Finance v. Omesh Misra Memorial Charitable Trust (2022) took a more literal and restrictive approach to Order XXI Rule 97. What prompted this narrower interpretation, and what were its consequences?

The Sriram Housing Finance case involved a bona fide purchaser of a property who was seeking to object to its execution. The Court meticulously examined the bare text of Order XXI Rule 97 and Rule 99. It noted that Rule 97 specifically deals with resistance or obstruction to possession of immovable property by “any person” obtaining possession of the property against the decree holder, and it empowers only the “decree holder” to make an application complaining about such resistance or obstruction.

Conversely, the Court observed that Rule 99 of Order XXI deals with the right of “any person” other than the judgment debtor who is dispossessed by the holder of a decree for possession. This provision, the Court held, vests “any person” with a right to make an application complaining about such dispossession.

Applying this literal reading to the facts of the case, the Court found that the appellant, being a bona fide purchaser and not the decree-holder, could not take shelter under Rule 97 to raise objections against the execution of the decree. Furthermore, since the appellant had never been dispossessed from the property (and in fact, contended to be in possession), they could not invoke Rule 99, which is specifically for making a complaint against “dispossession.”

The Sriram Housing Finance judgment concluded that since the appellant was neither entitled to make an application under Rule 97 nor Rule 99, Order XXI Rule 101 (which provides for determination of questions relating to disputes as to right, title, or interest arising between parties on an application made under Rule 97 or Rule 99) had no applicability. Consequently, the Executing Court, in entertaining the objections filed by the appellant, had transgressed the scope of Order XXI Rule 97 and Rule 99. The High Court’s decision to set aside the Trial Court’s order was thus affirmed.

The Current Dilemma and the Path Forward

The conflict between Brahmdeo Choudhary and Sriram Housing Finance presents a significant challenge for judicial clarity. Which interpretation best serves the interests of justice and the efficient administration of execution proceedings? Brahmdeo Choudhary champions the principle of natural justice, ensuring that no party with a legitimate claim is dispossessed without an opportunity to be heard, even if they are a stranger to the original decree. It prioritizes a complete adjudication within the execution proceedings, thereby preventing multiplicity of litigation. Sriram Housing Finance, on the other hand, adheres to a strict textual interpretation, emphasizing the specific roles assigned to decree-holders and dispossessed parties within the framework of Rules 97 and 99.

The Supreme Court, in P. Sumathi, has acknowledged this “arguable case” due to the conflict in precedents. The fact that the petitioner in P. Sumathi is still in possession of the decretal property further underscores the urgency of resolving this interpretive divergence. The Court’s order to maintain the petitioner’s possession until further leave of the Court indicates a cautious approach, recognizing the potential for irreparable harm if the Sriram Housing Finance precedent were to be strictly applied in all scenarios.

The Supreme Court’s decision in P. Sumathi will have far-reaching implications. It will definitively answer whether Order XXI Rule 97 CPC is an exclusive tool for decree-holders and auction purchasers, or if it extends its protective umbrella to any person facing actual or imminent dispossession during execution proceedings. The upcoming hearing in August 2025 will be a pivotal moment in clarifying this crucial aspect of civil procedure. The Court will need to carefully consider the legislative intent, the principles of natural justice, and the practical implications of both interpretations to arrive at a harmonious and consistent understanding of Order XXI Rule 97.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s impending decision in P. Sumathi v. K. Krishna Gounder & Ors. represents a watershed moment for the clarity and consistency of civil execution proceedings. Should the Court affirm the broader interpretation of Order XXI Rule 97 CPC, aligning with Brahmdeo Choudhary, it would reaffirm the fundamental principles of natural justice, ensuring that no individual, regardless of their status in the original decree, is dispossessed from property without a full opportunity to present their legitimate claims within the execution itself. This would foster a more inclusive and efficient dispute resolution mechanism, potentially reducing the need for multiple litigations and providing a robust safeguard against arbitrary evictions for third parties with independent rights.

Conversely, if the Court leans towards the stricter, literal reading adopted in Sriram Housing Finance, limiting the application of Rule 97 solely to decree-holders, it would prioritize textual fidelity and the streamlined execution process for successful litigants. While this could expedite the delivery of possession for decree-holders and auction purchasers, it might inadvertently push genuine third-party claimants into the more arduous path of separate suits under Rule 99 after dispossession, or even fresh litigation, potentially leading to increased hardship and protracted legal battles. The Supreme Court’s ultimate pronouncement will not only resolve this critical judicial inconsistency but will also define the very balance between procedural efficiency and the fundamental right to be heard in the realm of civil decree enforcement. How will the scales of justice tilt in this delicate equilibrium, and what ripple effects will this have on the labyrinthine corridors of Indian civil law?

Citations

- Civil Procedure Code,1908

- P. Sumathi v. K. Krishna Gounder & Ors. Special Leave to Appeal (C) No. 14092 of 2025

- Brahmdeo Choudhary v. Rishikesh Prasad Jaiswal(1997) 3 SCC 694

- Sriram Housing Finance v. Omesh Misra Memorial Charitable Trust 2022 SCC Online SC794

Expositors: Adv. Anuja Pandit