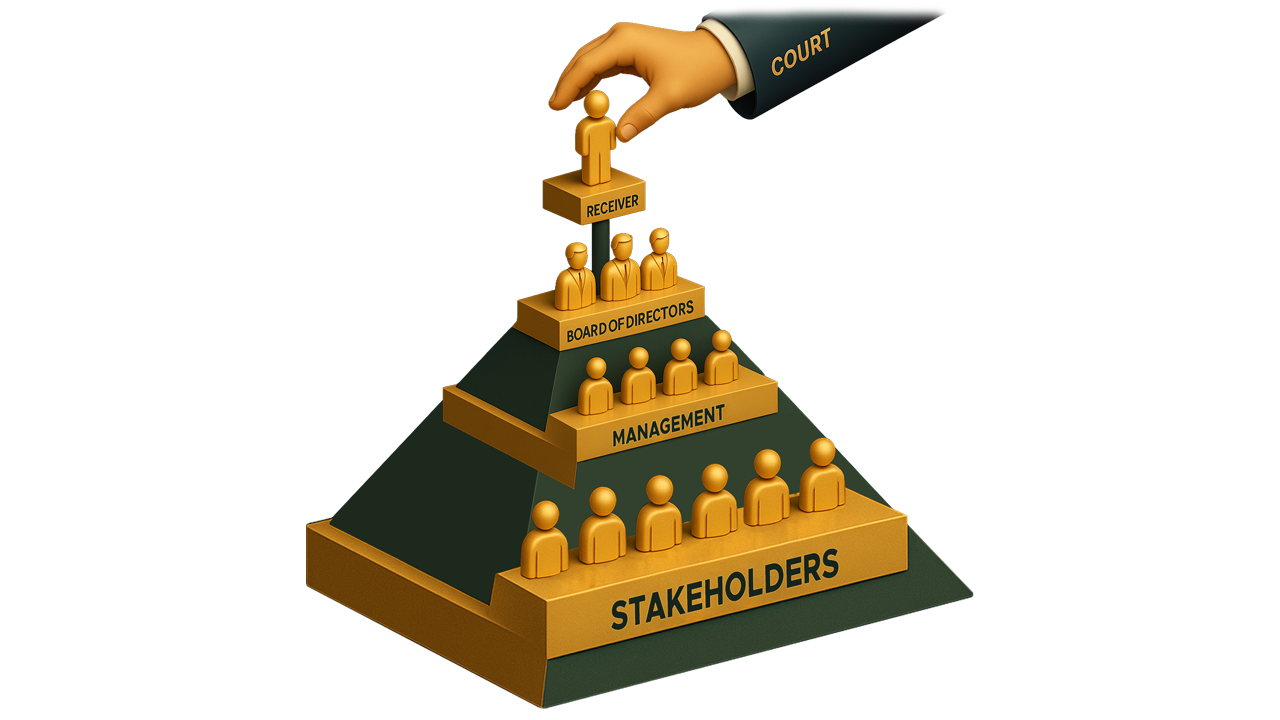

The appointment of an administrator or receiver in a company represents a significant judicial intervention, typically reserved for situations where the company’s affairs are in disarray, threatening its continued existence or the interests of its stakeholders. This measure is primarily undertaken to preserve the company’s assets, ensure its continuity as a going concern, and safeguard the rights of both shareholders and creditors. Both Indian and foreign legal precedents offer clear guidance on the circumstances that necessitate such appointments.

Indian courts have consistently stressed upon the critical need for an administrator or receiver’s appointment in instances of severe mismanagement, oppression, and when the company’s assets face imminent risk. This principle was recently affirmed by the Division Bench of NCLT (Kolkata) in Bhawri Law Sanei v. Dulichand Motors Pvt. Ltd. & Ors.1. Drawing upon earlier landmark decisions such as Pradip Kumar Sarkar & Ors. v. Luxmi Tea Co. Ltd. & Ors. (1990) 67 Comp Cas 91), and R.N. Jalan v. Deccan Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. & Ors. (1992) 75 Comp Cas 417), the tribunal held that to prevent further prejudice to the company and its shareholders, an administrator’s appointment becomes crucial for preserving the company’s vital interests.

This judicial stance was further strengthened by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Arun Gupta & Anr. v. South Eastern Carries Limited & Ors.2 where Justices DY Chandrachud and MR Shah upheld the NCLT’s decision to appoint a Special Officer. The Supreme Court highlighted several key situations that warrant such an appointment, including cases where the company is mismanaged and certain actions are prejudicial to the company’s and other shareholders’ interests. The presence of continuous acts of oppression and mismanagement, coupled with various allegations and grievances among the parties, often points to a dysfunctional corporate environment. Furthermore, the depletion of company assets because of mismanagement serves as a strong indicator that external intervention is required. The Supreme Court also referenced the NCLT’s broad powers under Section 242(4) of the Companies Act, which allows it to make any interim order deemed fit for regulating the company’s affairs on just and equitable terms, thereby enabling the tribunal to ensure that resolutions passed in Board Meetings shall not be prejudicial to the interest of the Respondent Company, thus preventing frivolous litigation.

More recently, the NCLT New Delhi in Ms. Kanta Agarwala & Anr. v Exclusive Capital Limited & Ors3, similarly concluded that the respondent company’s affairs were being run prejudicially, mismanaged, and funds were being misused and siphoned off, leading to the necessary appointment of an administrator/receiver. In a parallel decision, NCLT Kochi, in Malabar Construction Materials Pvt. Ltd. v. K Mohammed & Ors.4 appointed an administrator due to the current board of directors’ inability to make favourable decisions for the company’s smooth operation, thereby ensuring its continuity as a going concern.

Foreign Precedents: A Comparative View

While the Indian legal framework has developed its own nuanced approach to corporate oversight, foreign precedents, particularly from English and American courts, offer valuable comparative insights into the universal principles governing the appointment of receivers.

In the UK, receivership primarily safeguards the interests of secured creditors. Governed by the Insolvency Act, 1986 and specific secured creditor agreements, a receiver is typically appointed by a secured creditor to assume control of a company’s assets and operations with the objective of recovering outstanding debts. This usually occurs when a company struggles to meet its debt obligations, and the receiver’s primary role is to liquidate assets to repay creditors. Intervention may be warranted if there’s reason to apprehend that the applicant will be in a worse situation if the appointment is delayed, as in Thomas v. Davies, (1847) 11 Beav 29 (O). Conversely, a receiver will not be appointed if there is no immediate danger to the property or other urgent reason, a principle upheld in Whitworth v. Whyddon5 and Micklethwait v. Micklethwait6. The court’s fundamental duty is to protect the property for the benefit of its rightful owner, as illustrated by Blakeney v. Dufaur7.

In the US, the power of appointment of a receiver is frequently invoked to prevent fraud, safeguard the subject of litigation from material injury, or rescue it from threatened destruction. While courts are hesitant to disturb possession when only title is disputed, they will intervene with a receiver for property security if the property is exposed to danger and loss, and the current possessor lacks a clear legal right. These principles, clearly articulated in T. Krishnaswamy Chetty v. C. Thangavelu Chetty and Ors.8, resonate with the protective intent observed across various jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The appointment of an administrator or receiver, whether in India, the UK, or the US, fundamentally serves as a protective and preventive measure. While the specific legal frameworks and the primary beneficiaries might vary—focusing on shareholders and the company’s going concern in India, versus secured creditors in the UK—the underlying rationale remains consistent: to intervene when a company’s assets, operations, or the interests of its legitimate stakeholders are in peril due to mismanagement, oppression, or other serious issues. This intervention is designed to restore order, preserve value, and ultimately ensure a just and equitable outcome in challenging corporate circumstances, reinforcing the judiciary’s role as a guardian of corporate governance and stakeholder rights.

Citations:

- Company Petition No. 246/KB/2023

- Civil Appeal No. 1024 of 2021

- Company Petition No. 48/(ND)/2024

- IA(C/ACT)/10/KOB/2024 of CP(C/ACT)/16/KOB/2020

- (1850) 2 Mac & G 52 (S)

- (1S57) 1 De G & J 504 (U)

- (1851) 15 Beav 40 (V)

- AIR 1955 MAD 430

Expositor(s): Adv. Khushboo Saraf