The IBC1 stands as a comprehensive legal edifice designed to resolve financial distress. Within its intricate framework, Section 79(15)(a) acts as a specific carve-out, declaring that a “liability to pay fine imposed by a court or tribunal” lies beyond the grasp of bankruptcy proceedings.This seemingly clear demarcation, however, encounters turbulence when confronted with penalties levied by regulatory behemoths like the SEBI2, igniting a legal tug-of-war.

Section 79 of the IBC meticulously defines the lexicon of Part III, governing insolvency resolution and bankruptcy for individuals and partnerships. Sub-section(15) meticulously lists “excluded debts,” obligations that a bankrupt individual isn’t compelled to discharge through the bankruptcy process.

At the forefront of this list is clause (a), addressing the “liability to pay fine imposed by a court or tribunal.” The rationale underpinning this exclusion likely resides in the inherently punitive nature of fines, instruments intended to chastise wrongdoing and deter future transgressions, rather than merely addressing financial woes. Allowing such penalties to be swept away by bankruptcy could dilute their deterrent effect, potentially offering a loophole for evading the consequences of unlawful conduct. Consequently, the Ld. NCLT Hyderabad , against which the present appeal is furthered, posited that the pecuniary penalty imposed by SEBI inherently aligned with the definition of a “fine,” thus classifying it as an “excluded debt” under Section 79(15)(a), placing it firmly outside the Appellant’s bankruptcy proceedings.

Yet, this interpretation has not gone unchallenged. A potentially contrasting perspective emerged from the Calcutta bench of the NCLAT3 in the present appeal of G.V. Marry Vs. Union Bank Of India4. The NCLAT, in this judgment, drew a distinction, asserting that penalties imposed by SEBI do not automatically fall under the umbrella of “fine” as envisioned by Section 79(15)(a) of the IBC. The crux of the G.V. Mary ruling lay in differentiating between penalties meted out by traditional courts or tribunals and those imposed by regulatory bodies for breaches of specific regulations. The NCLAT reasoned that SEBI, while wielding quasi-judicial authority, primarily functions as a market regulator ensuring compliance, and its penalties are more akin to regulatory sanctions than outright punitive fines for criminal acts. This distinction carries significant weight for individuals grappling with both bankruptcy and regulatory penalties.

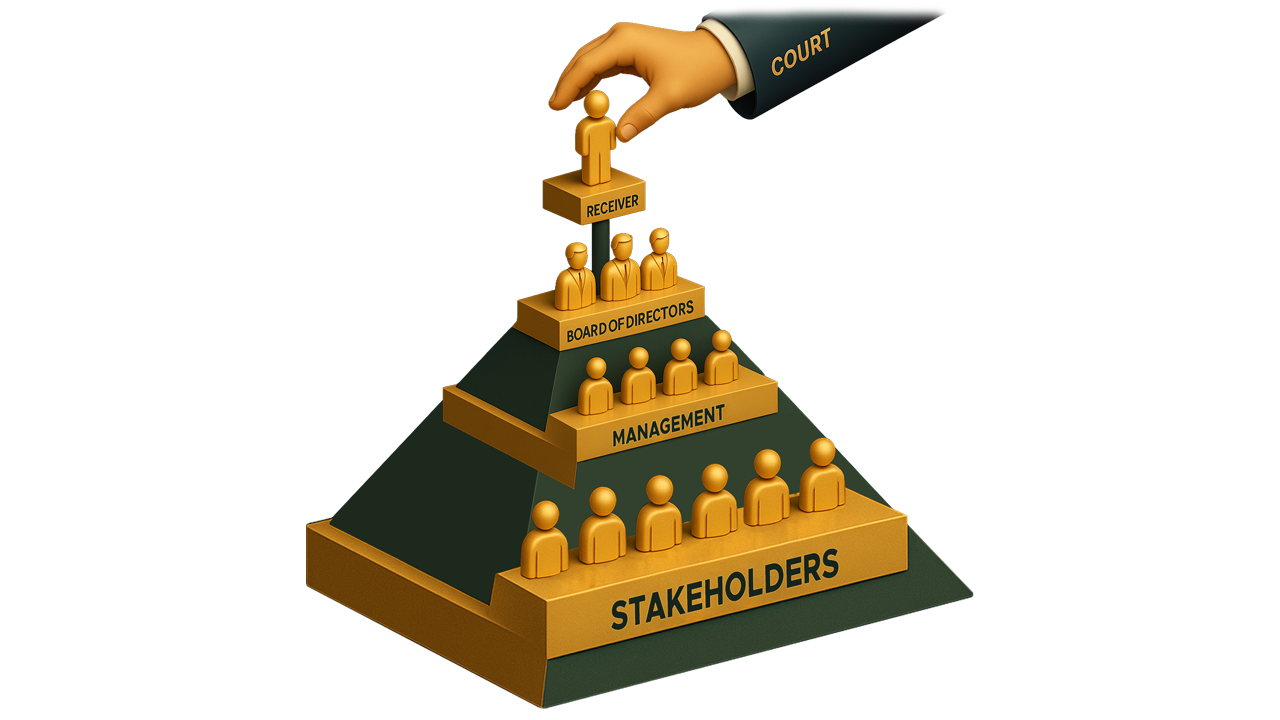

Thus, the central legal riddle before the appellate court in this case became whether the monetary penalty levied by SEBI should be categorized as a “fine” under Section 79(15)(a) of the IBC, thereby excluding it from the bankruptcy proceedings initiated by the Appellant, a Personal Guarantor for BRG Energy Limited.

The Appellant, feeling aggrieved by the Ld. NCLT’s stance, contended that the term “fine” in Section 79(15)(a) should not encompass penalties imposed by SEBI. To bolster this argument, the Appellant’s counsel invoked a decision by the Hon’ble High Court of Telangana in G. Bala Reddy and 5 Others Vs. Securities Exchange board of India and Another5. This legal battle involved multiple petitioners challenging a SEBI demand notice for penalties, alleging its illegality and arbitrariness. The Appellant’s reliance suggested a belief that SEBI penalties possessed a distinct character from the “fines” contemplated by the IBC’s exclusionary clause. The underlying argument posited that treating SEBI penalties as excluded debts would unfairly burden already distressed individuals and potentially undermine the IBC’s objective of holistic financial resolution.

At this juncture, the appellate court offered a crucial contextualization of the Telangana High Court judgment. It clarified that the Hon’ble Single Judge’s ruling of September 19, 2023, was specifically tethered to the demand notice issued on November 23, 2021, under the SEBIA6. The findings concerning the IBC’s potential overriding effect under Section 238 and the implications of a moratorium were deemed applicable solely to that particular SEBI demand notice under scrutiny. The appellate court underscored that the Single Judge’s conclusion – classifying SEBI penalties as “fines” and consequently “excluded debts” under Section 79(15)(a) – was confined to the specific factual landscape of that case and could not be automatically applied beyond it.

So, with the Telangana High Court’s view now firmly within its specific context, the appellate court embarked on its own reasoning to unravel the core question: did the Ld. NCLT Hyderabad correctly categorizes the SEBI penalty as an “excluded debt”? The court initiated its analysis by probing the legislative intent behind Section 79(15)(a). Why the explicit exclusion of “fines imposed by a court or tribunal”? The court surmised that this exclusion stemmed from the inherently punitive nature of fines, designed to penalize wrongdoing and deter future misconduct. Allowing such penalties to be erased through bankruptcy could erode their deterrent effect, potentially enabling individuals to evade accountability for their unlawful actions.

The pivotal point of contention remained: did a SEBI-imposed penalty unequivocally fit the legislative definition of a “fine” under Section 79(15)(a)? The Appellant, drawing strength from the Telangana High Court’s observations, argued that SEBI penalties were more akin to regulatory sanctions aimed at ensuring market compliance rather than traditional punitive fines for criminal offenses.

However, the appellate court found compelling reasons to align with the Ld. NCLT’s initial assessment. It noted that a subsequent Division Bench of the Telangana High Court, in G.Bala Reddy VS. Securities Exchange board of India7, had deliberately refrained from definitively labeling SEBI levies as either “fine” or “penalty,” leaving the issue open for determination in “appropriate proceedings.” This judicial hesitation within the same High Court indicated a lack of a settled view on the matter.

Crucially, the appellate court then turned its gaze towards the pronouncements of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Saranga Anil Kumar Aggarwal V. Bhavesh Dhirajlal Sheth and Others8. Paragraph 32 of this judgment proved to be a guiding light. The Supreme Court explicitly stated that Section 79(15) of the IBC includes “liabilities arising from fines imposed by courts or tribunals” within the definition of “excluded debts.” More significantly, the Apex Court categorized these excluded debts, including fines, as possessing a “statutory, penal, or personal” character, thus placing them beyond the reach of discharge under the insolvency resolution process.

The appellate court drew a critical analogy. The Saranga Anilkumar Aggarwal case, while originating from the NCDRC9, involved penalties imposed by a regulatory body for breaches of consumer protection laws. The Supreme Court explicitly held that these NCDRC penalties were “regulatory in nature” and, consequently, the moratorium under Section 96 of the IBC did not extend to them.

Reasoning by this analogy, the appellate court concluded that penalties imposed by SEBI, being similarly “regulatory in nature” and stemming from breaches of securities laws, should be treated analogously. Just as the Supreme Court had determined for NCDRC penalties, the appellate court reasoned that SEBI penalties logically fell within the scope of “excluded debt” as envisioned by Section 79(15) of the IBC.

Therefore, the appellate court firmly held that the Ld. NCLT Hyderabad’s observation in paragraph 16 of the impugned order, classifying the SEBI penalty as a “fine” and consequently an “excluded debt,” was in harmony with the statutory provisions of Section 79(15)(a) and the principles enunciated by the Hon’ble Supreme Court. The court found no basis to deem this observation either arbitrary or contrary to the legislative intent.

Ultimately, the appeal met its dismissal. The court’s well-articulated reasoning underscored a fundamental principle: while the IBC strives for comprehensive insolvency resolution, it consciously carves out exceptions for liabilities possessing a punitive or regulatory essence. Penalties imposed by regulatory bodies like SEBI, akin to those levied by the NCDRC, fall squarely within this exception, ensuring that individuals cannot employ bankruptcy proceedings as a shield against the consequences of their regulatory non-compliance. The legal drama concluded, affirming the primacy of regulatory sanctions within the framework of bankruptcy law, delivering a clear message about the limits of insolvency relief in the face of regulatory penalties.

Conclusion

This judicial pronouncement draws a definitive line, clarifying that penalties imposed by SEBI, in the eyes of the court, fall squarely within the definition of “fine” under Section 79(15)(a) of the IBC, thus placing them beyond the reach of bankruptcy proceedings. The decision underscores a judicial deference to the punitive and regulatory nature of such penalties, aligning them with the legislative intent to exclude certain liabilities from discharge.

The future implications of this decision are significant. It establishes a precedent that individuals facing financial distress cannot necessarily use the IBC as a shield against penalties levied by financial regulators. This ruling reinforces the authority of regulatory bodies like SEBI and ensures that their enforcement mechanisms remain effective, even in the face of personal insolvency. It signals that the pursuit of market integrity and regulatory compliance will not be easily circumvented by bankruptcy filings.

However, this decision also raises a potential future question: Could the nature and purpose of a regulatory penalty, beyond its mere pecuniary aspect, become a point of contention in future bankruptcy cases? For instance, if a regulatory penalty is primarily compensatory rather than punitive, would it still fall under the “fine” exclusion of Section 79(15)(a), or could a distinction based on the penalty’s underlying objective be argued before the courts? This remains a potential avenue for future legal debate as the interplay between bankruptcy law and the powers of various regulatory bodies continues to evolve.

Citations

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016

- Securities and Exchange Board of India

- National Company Law Appellate Tribunal

- Company Appeal (AT) (CH) (Ins) No.165/2025

- Writ Petition No. 34761 of 2021

- Securities and Exchange Board of India Act,1992

- Writ Appeal No. 218 of 2024

- Civil Appeal No. 4048 of 2024

- National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit