Introduction

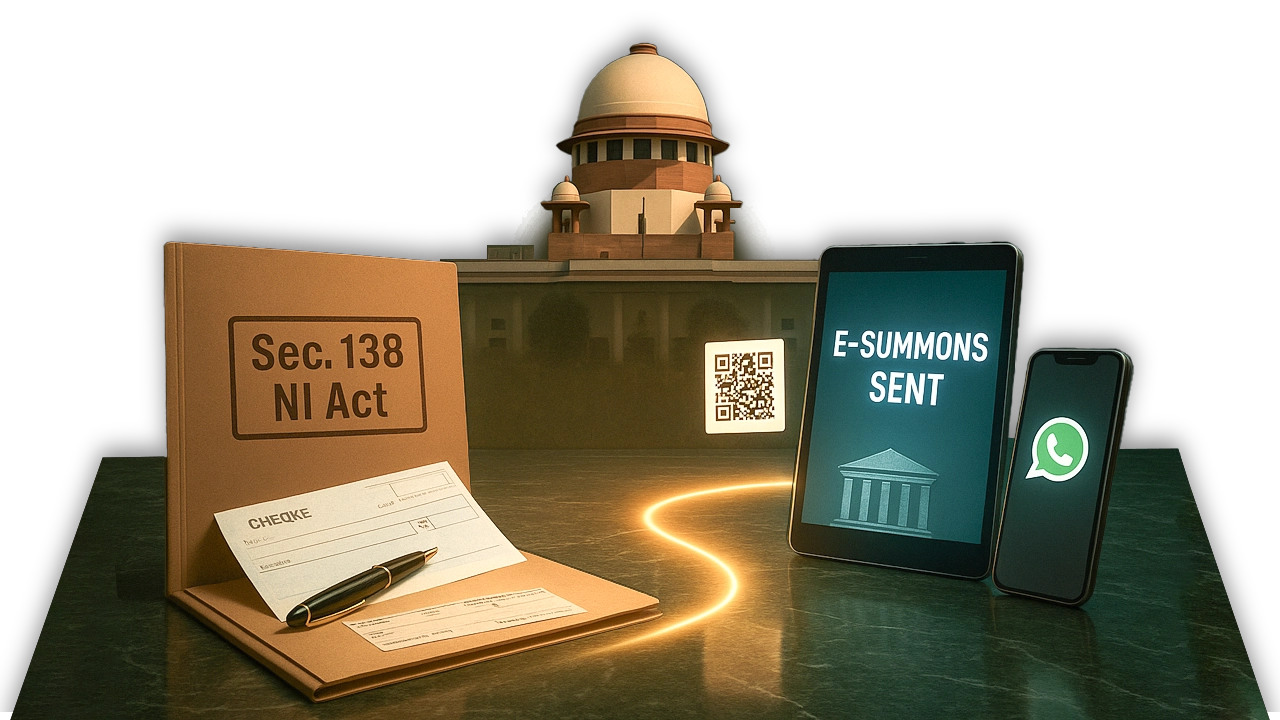

The Supreme Court of India’s decision in Sanjabij Tari v. Kishore S. Borcar and Anr1. has been hailed as a pivotal moment for procedural reform, primarily addressing the massive and debilitating backlog of cheque bouncing cases under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments (NI) Act, 1881. The Court clearly articulated that the legislative intent behind criminalising cheque dishonour is not punitive retribution, but rather to ensure the payment of money and uphold the credibility of cheques as a reliable substitute for cash payment. With Section 138 cases consuming an overwhelming portion nearly 50% in certain jurisdictions of the judicial system’s time, this judgment provided a necessary systemic overhaul.

The core of the legal contention was an appeal challenging a High Court’s decision to acquit the accused, which had erroneously set aside the concurrent convictions by the lower courts. The dispute centered on a dishonoured cheque issued following a loan transaction. The High Court had overturned the conviction primarily by questioning the financial capacity of the complainant to advance the loan, effectively accepting the defense that the cheque was merely a signed blank instrument. This approach was held to be fundamentally flawed. The apex court firmly reiterated the long-standing principle that once the accused admits the execution of the cheque, the statutory presumptions under Section 118 and Section 139 of the NI Act immediately arise. While this presumption is rebuttable, the initial burden of proof to show that the cheque was not in discharge of any debt or liability falls squarely on the accused.

The Supreme Court explicitly set aside a contrary judicial view that cash transactions above ₹20,000/- would not be a ‘legally enforceable debt‘ due to a mere violation of the Income Tax Act. It reinforced its stance by citing precedents, including Mishri Lal v. State of MP2 , establishing that a minor violation of an allied statute, in this case, the Income Tax Act, only attracts a penalty under that Act and does not automatically render the underlying debt void or unenforceable under the NI Act. Further, the Court referenced Kaushalya Devi Massand v. Roopkishore Khore3 to emphasize that the true purpose of the NI Act is to ensure the effectiveness of negotiable instruments and that judicial procedures should be geared towards summary disposal. By firmly establishing this rationale, the Court corrected the trend of lower courts unduly prolonging trials and treating NI Act proceedings as conventional civil recovery suits.

Recently, the High Court of Karnataka in Ashok Vs. Fayaz Aahmad4, (2025) HC has taken the view that since NI Act is a special enactment, there is no need for the Magistrate to issue summons to the accused before taking cognizance under (Section 223 of BNSS) of complaints filed under Section 138 of NI Act. The Supreme Court is in agreement with the view taken by the High Court of Karnataka. Consequently, the Hon’ble Court directs that there shall be no requirement to issue summons to the accused in terms of Section 223 of BNSS i.e., at the pre-cognizance stage.

To buttress the goal of promoting speedy and effective justice, the Supreme Court laid down a comprehensive set of guidelines to be implemented across the country:

Service of Summons Reform: Service of summons shall not be confined through prescribed usual modes but shall also be issued dasti. Trial Courts must also adopt electronic means like e-mail, mobile number, and/or WhatsApp details for service, provided the complainant furnishes the details with a verifying affidavit. The complainant is required to file an affidavit of service.

Settlement and Online Payment: Principal District and Sessions Judges must create and operationalise dedicated online payment facilities. The summons must explicitly inform the accused of the option to make payment of the cheque amount directly through the online link at the initial stage.

Pleadings and Trial Procedure: Every complaint must now contain a synopsis in a specified format. There shall be no requirement to issue summons to the accused at the pre-cognizance stage. To ensure the swiftness of summary trials, the Trial Court must record sufficient reasons before converting a summary trial to a summons trial. At the initial post-cognizance stage, the Court is empowered to ask specific questions to the accused to ascertain the nature of the defence.

Interim Deposit and Court Type: The Trial Court should proactively use its power to order the payment of an interim deposit under Section 143A of the NI Act as early as possible. After service of summons, matters must be placed before physical Courts, though matters may be listed before digital courts prior to service. High Courts were also directed to set up realistic pecuniary benchmarks for evening Courts hearing these cases.

Monitoring Mechanism: High Courts of Delhi, Bombay, and Calcutta are requested to form Administrative Committees to monitor pendency and explore solutions. District and Sessions Judges in these jurisdictions must also maintain a dedicated dashboard to reflect the pendency and progress of Section 138 cases.

Revised Compounding Guidelines: The Court also outlined revised guidelines for compounding offences under the NI Act, suggesting increasing percentages of the cheque amount to be deposited for compounding at different stages of the trial, starting from a base amount and increasing if the amount is tendered before the Trial Court, Sessions Court, or the Supreme Court.

Conclusion

This landmark ruling unequivocally strengthens the legal framework surrounding the NI Act by streamlining the process, curtailing unnecessary delays, and reinforcing the foundational principle that a bounced cheque is a matter of serious legal consequence. The comprehensive guidelines, slated for implementation by November 1, 2025, represent a major step towards decongesting the judicial docket and upholding the integrity of commercial transactions in India. The appeal itself was allowed, setting aside the High Court’s erroneous acquittal and restoring the conviction with a direction to the accused to comply with the restored orders, thereby achieving both systemic reform and individual justice.

Citations

- Sanjabij Tari v. Kishore S. Borcar and Anr. Criminal Appeal No. 1755 of 2010

- Mishri Lal v. State of MP Criminal Appeal No. 489 of 1996.

- Kaushalya Devi Massand v. Roopkishore Khore, Criminal Appeal No.723 of 2011

- Ashok v. Fayaz Aahmad, (2025) Criminal Petition No.101514 of 2025

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla