Introduction

The Supreme Court’s recent and impactful judgment in Kaveri Plastics v. Mahdoom Bawa Bahrudeen Noorul1 (2025) has established a significant precedent for those navigating cheque dishonour cases. The ruling powerfully reinforces the principle that strict adherence to legal procedures is mandatory, even when faced with what may appear to be a trivial error. This landmark decision serves as a powerful reminder that in the domain of penal statutes, particularly Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 (NI Act), absolute precision is paramount, as a seemingly minor oversight can have fatal consequences for a legal case. The judgment underscores that even a minor lapse in drafting a demand notice can be the difference between a successful prosecution and the dismissal of a case.

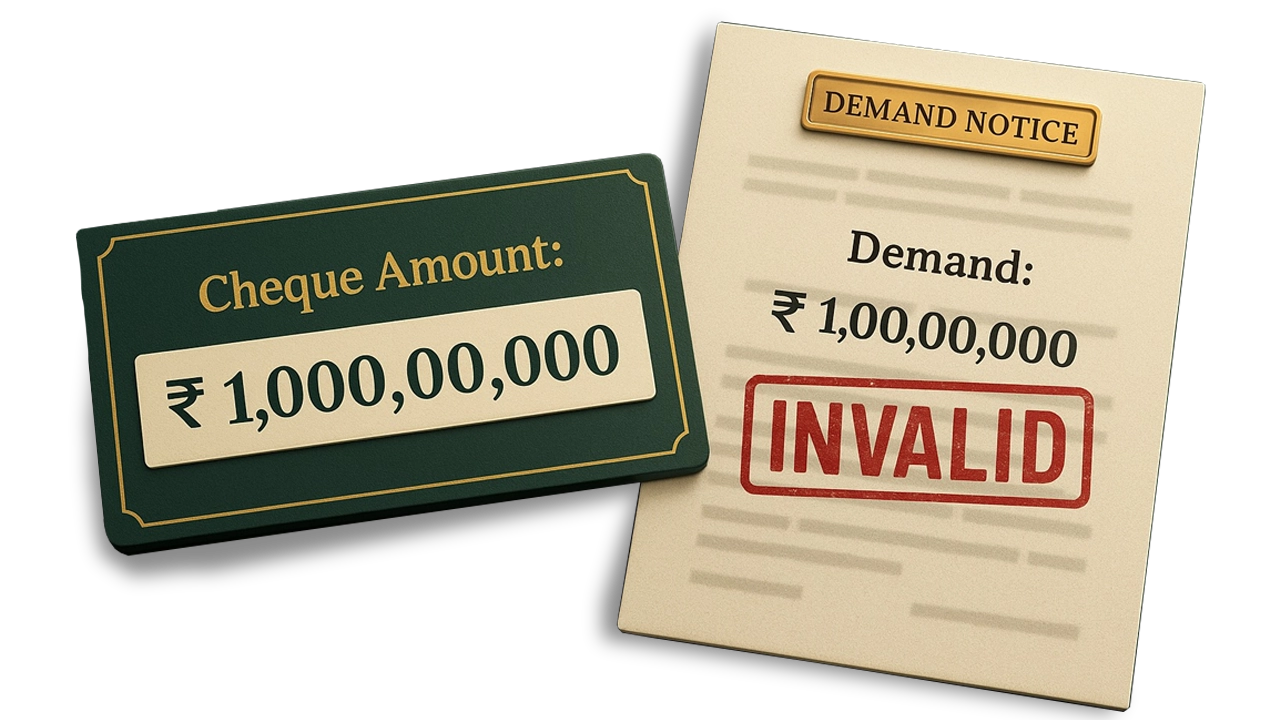

The genesis of this landmark decision lies in a case where a cheque for ₹1,00,00,000/- was issued, but upon its dishonour, the complainant sent a demand notice that mistakenly demanded ₹2,00,00,000/-. This discrepancy, which the complainant claimed was a mere “typographical error” from a cut-and-paste command, became the central point of contention. The case highlighted the critical question of whether such an error could be overlooked in the interest of substantive justice. The Supreme Court, upholding the High Court’s decision, quashed the criminal complaint, establishing a firm legal position on the matter.

In its meticulous analysis, the Court dismantled the “typographical error” defence, leaving no room for leniency. The heart of the matter, it held, lay in the mandatory nature of the demand notice under Section 138 of the NI Act. The Court was unyielding in its interpretation: the phrase “said amount of money” must refer explicitly and exclusively to the exact sum for which the cheque was drawn. This uncompromising stance, it argued, was not a mere technicality but a foundational principle of a penal statute. To solidify this position, the Court drew upon a string of judicial precedents. Cases like Suman Sethi v. Ajay K. Churiwal & Anr2. and M/s. Yankay Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Ltd. v. CITI bank3 were cited to underscore that any deviation in the demanded amount, whether higher or lower, is a fatal blow to the prosecution.

The Court further referenced K. Gopal v. Mr. T. Mukunda4 and Sunglo Engineering India Pvt. Ltd. v. The State & Ors5., which consistently held that notices with discrepancies were defective and grounds for quashing a complaint. This rich tapestry of case law demonstrated a clear, unwavering judicial consensus: precision in the demand notice is not a suggestion but a strict, non-negotiable legal requirement.

The Court also relied on the principle of strict construction of penal statutes. It cited M. Narayanan Nambiar v. State of Kerala6, which, quoting the English case Dyke v. Elliott7 stated that courts must ensure “the thing charged as an offence is within the plain meaning of the words used, and must not strain the words on any notion that there has been a slip”. This principle was also affirmed in Balaji Traders v. State of U.P. & Anr8.

Furthermore, in K.K. Ahuja v. V.K. Vora & Anr9., the Court stated that there is “no question of inferential or implied compliance” with the conditions of the NI Act. The judgment in Rahul Builders v. Arihant Fertilizers & Chemicals & Anr10. highlighted that unless a notice is “served in conformity with proviso (b) appended to Section 138 of the Act, the complaint petition would not be maintainable”.

In Gokuldas v. Atal Bihari & Anr11., the High Court of Madhya Pradesh also observed that every “technical formality” required under Section 138 must be “complied with strictly”. This firm stance was echoed in Chhabra Fabrics Private Limited v. Bhagwan Dass12, where a discrepancy in the cheque number was also deemed a non-compliance with the mandatory provisions of the NI Act. Finally, the Court in Dashrathbhai Trikambhai Patel v. Hitesh Mahendrabhai Patel & Anr13. reiterated that the notice demanding payment of the “said amount of money” must be interpreted to mean the “cheque amount”.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision in the present judgement is a significant development with far-reaching implications for the legal landscape in India. It emphasizes that while the NI Act’s purpose is to instill confidence in commercial transactions, it does not permit a lax approach to the procedural safeguards it provides to the accused. The judgment underscores that even a minor lapse in drafting a demand notice can be the difference between a successful prosecution and the dismissal of a case. For legal professionals and businesses, this serves as a powerful call to action: to ensure every detail in a demand notice is meticulously cross-verified to protect their legal recourse and avoid the costly consequences of a technical error. The ruling ensures a more consistent application of the law, bringing clarity and promoting a higher standard of practice in the filing of cheque dishonour complaints.

Citations

- Kaveri Plastics v. Mahdoom Bawa Bahrudeen Noorul 2025 INSC 1133

- Suman Sethi v. Ajay K. Churiwal & Anr. (2000) 2 SCC 380

- M/s. Yankay Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Ltd. v. CITI bank 2001 DCR 609

- K. Gopal v. Mr. T. Mukunda Criminal Appeal No.1011 of 2010

- Sunglo Engineering India Pvt. Ltd. v. The State & Ors. MANU/DE/3805/2021

- M. Narayanan Nambiar v. State of Kerala AIR 1963 SC 1116

- Dyke v. Elliott (1872) 4 PC 184

- Balaji Traders v. State of U.P. & Anr. 2025 SCC OnLine SC 1314

- K.K. Ahuja v. V.K. Vora & Anr (2009) 10 SCC 48

- Rahul Builders v. Arihant Fertilizers & Chemicals & Anr. (2008) 2 SCC 321

- Gokuldas v. Atal Bihari & Anr. MCRC 5458/2013

- Chhabra Fabrics Private Limited v. Bhagwan Dass Crl. Appeal No.1772-SB of 2002

- Dashrathbhai Trikambhai Patel v. Hitesh Mahendrabhai Patel & Anr. (2023) 1 SCC 578

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla