Introduction

Navigating the Indian legal system can be a complex affair, especially when it comes to fundamental rights like personal liberty. A person fearing arrest in a non-bailable offence can seek anticipatory bail, a legal provision that grants pre-arrest protection. But where do they go to seek this relief? Do they have to go to a lower court first, or can they go directly to the High Court? This seemingly simple question has led to a fascinating and sometimes contradictory journey through judicial pronouncements.

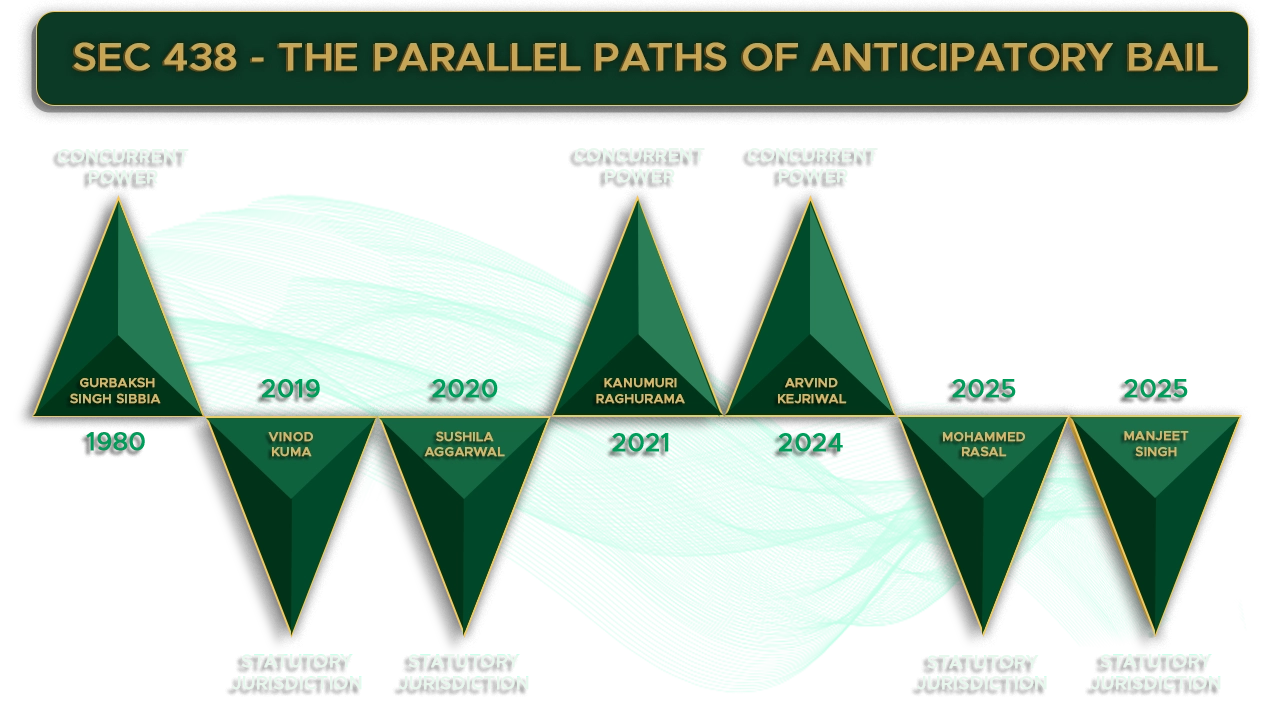

The legal provision for anticipatory bail, now found in Section 438 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita BNSS1, provides concurrent jurisdiction to both the Sessions Court and the High Court. This means that a person can technically approach either court. As with many legal matters, the black letter of the law is one thing, and judicial interpretation and practice are quite another. This has resulted in a “flip-flop” in judicial views on the matter, creating a legal quandary for those seeking justice.

So, what is the core of this legal dilemma? On one hand, you have the statutory provision granting concurrent jurisdiction, and on the other, you have the principle of judicial hierarchy and a desire to prevent the higher courts from being overwhelmed. The Supreme Court has grappled with this tension for decades, leading to a series of judgments that have shaped, and at times reshaped, the legal landscape.

One of the earliest and most authoritative pronouncements on this subject came in the landmark case of Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia v. State of Punjab2 (1980). A five-judge bench, in a foundational judgment, unequivocally declared that there is no hierarchy that requires an accused to first approach the Sessions Court. The Court stated that the High Court and Sessions Court have concurrent powers, and a direct approach to the High Court is permissible. This decision set the stage for a liberal interpretation of the law, affirming the right of an individual to choose their forum.

Has this principle been consistently upheld over the years? The answer lies in the reaffirmation of this position in Sushila Aggarwal & Ors v. State (NCT of Delhi)3 (2020), where the Supreme Court clarified that while the practice of approaching the Sessions Court first is a matter of judicial discipline and orderly procedure, it is not a statutory prescription. The Court emphasized that in justified circumstances, a High Court may be approached directly. Similar observations followed in Kanumuri Raghurama Krishnam Raju v. State of Andhra Pradesh4 (2021) and Arvind Kejriwal v. Directorate of Enforcement5 (2024), where the Court consistently held that the “Sessions-first” approach is not an inflexible rule, and a direct approach to the High Court is permissible in appropriate or exceptional cases.

How, then, do we reconcile this with the more recent judicial observations? The legal position on anticipatory bail is a bit like a pendulum swinging back and forth. In a 2025 order in Mohammed Rasal.C & Anr. Versus State of Kerala & Anr6., a bench comprising Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta expressed strong disapproval of the practice of directly entertaining applications for anticipatory bail in the High Court. While acknowledging concurrent jurisdiction, the bench opined that the High Court should only entertain such matters in “exceptional cases” with “special reasons to be recorded.” The Court’s rationale was rooted in judicial hierarchy and efficiency. It feared that if High Courts were flooded with such applications, it would lead to a “chaotic situation.” This view aligns with the Allahabad High Court’s position in Vinod Kumar v. State of U.P7. (2019), which also stressed the need for “strong, cogent, and compelling reasons” to bypass the Sessions Court. The Court further noted that Sessions Judges have a “direct and first-hand assistance” of the Public Prosecutor and “immediate access to the Case Diary,” facilitating a better appreciation of facts.

But does this represent a definitive shift in judicial thinking? Just a month before this, another bench of the Supreme Court, in Manjeet Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh8 (2025), seemingly took a different stance. Justices Sanjay Kumar and NV Anjaria set aside an order of the Allahabad High Court that had refused to entertain an anticipatory bail application for not first approaching the Sessions Court. Citing the Kanumuri Raghurama Krishnam Raju and Arvind Kejriwal judgments, the bench observed that it is not necessary for an accused to first approach the Sessions Court as a rule.

So, where does this leave the litigant? The legal community is left to wonder: will the Supreme Court settle the issue with a definitive ruling that reconciles these conflicting views? Or will it continue to be a matter of judicial discretion, leaving litigants to navigate the uncertainty? The appointment of Senior Advocate Sidharth Luthra as amicus curiae in the Mohammed Rasal case indicates the Court’s seriousness in addressing this matter head-on. The legal community waits with bated breath to see if a final, clear path will emerge from this complex web of judicial pronouncements.

Conclusion

This jurisprudential flip-flop on anticipatory bail, where the Supreme Court has offered divergent opinions on the same point of law, creates a precarious situation for both the judiciary and the public. For practitioners, it introduces an element of unpredictability, making it difficult to advise clients with certainty on the proper forum to approach. A lawyer may file directly in the High Court based on one bench’s observation, only to face rejection by another bench that prioritizes the “Sessions-first” approach. This not only leads to wasted judicial time but also puts the personal liberty of the accused at risk, as a denial at the first instance could lead to immediate arrest without the chance to appeal. The legal fraternity is left navigating a labyrinth of conflicting precedents, creating a perception of an inconsistent and fractured justice system.

The most significant ramification of these diverged judgments is the potential erosion of legal certainty. When a foundational principle, such as the maintenance of judicial hierarchy, appears to be in flux, it can lead to a state of doctrinal disarray. This confusion extends beyond the bar, affecting the very functioning of the High Courts, as some may adopt a strict “Sessions-first” rule while others entertain direct applications on a case-by-case basis. The conflicting views also undermine the very idea of a uniform rule of law across the country. The lack of a clear, singular position from the apex court on such a critical matter raises a fundamental question about the binding nature of its pronouncements, particularly when benches of coordinate strength seem to be contradicting each other.

Looking ahead, this issue will undoubtedly continue to be a subject of intense debate. What criteria will the Supreme Court ultimately establish for “exceptional circumstances” that justify a direct approach to the High Court? Will a larger bench be constituted to definitively settle the law and provide a clear, binding precedent for all lower courts to follow? Furthermore, in an era of digital communication and virtual filings, will the traditional rationale of avoiding a “chaotic situation” hold up, or will technology force a re-evaluation of how courts manage the flow of such applications? The answers to these questions will be pivotal in shaping the future of bail jurisprudence and, more broadly, in restoring a sense of predictability and coherence to the Indian legal system.

Citations

- Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita,2023

- Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia v. State of Punjab (1980) 2 SCC 565

- Sushila Aggarwal & Ors v. State (NCT of Delhi) AIRONLINE 2020 SC 74

- Kanumuri Raghurama Krishnam Raju v. State of Andhra Pradesh Crl.A. No. 000515 / 2021

- Arvind Kejriwal v. Directorate of Enforcement 2024 INSC 512

- Mohammed Rasal.C & Anr. Versus State of Kerala & Anr. Special Leave Petition (Crl.) No. 6588/2025

- Vinod Kumar v. State of U.P. Criminal Misc. Bail Application No. – 53729 Of 2019

- Manjeet Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh 2025:AHC-LKO:12258

Expositor (s): Adv. Archana Shukla, Adv Anuja Pandit