The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 (SARFAESI Act), stands as a cornerstone in India’s financial regulatory framework. Its primary objective, as gleaned from its Preamble, is to bolster the financial health of banks and financial institutions. This is achieved by empowering them to recover non-performing assets (NPAs) with greater speed and efficiency, notably by allowing secured creditors to enforce their security interests without direct judicial intervention. This marked a significant paradigm shift in India’s legal and financial landscape.

Legal Framework and Debt Recovery Provisions

For the effective enforcement of debt recovery, the DRT1 were established under the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act (RDDBFI Act). These specialised forums enable secured creditors to recover debts swiftly. Appeals against DRT orders can be made to the Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunal (DRAT), ensuring a balanced resolution process. Notably, both DRTs and DRATs wield powers akin to civil courts under Section 22 of the RDDBFI Act, allowing them to adjudicate debt recovery matters with precision.

Under Section 13 of the SARFAESI Act, secured creditors are permitted to directly recover their dues from borrowers without the necessity of approaching a court or tribunal. Once a borrower’s account is classified as an NPA, the creditor can issue a notice under Section 13(2), detailing the outstanding debt and identifying the secured assets slated for recovery. The borrower is granted a 60-day window to repay the debt or raise objections. And if the borrower fails to comply, the secured creditor is empowered by Section 13(4) to take various measures, including taking possession of the secured asset, assuming management of the business, appointing a manager, or instructing third parties to pay amounts owed to the borrower directly to the creditor.

Safeguards for Aggrieved Borrowers: Section 17

Despite the extensive powers vested in secured creditors, the SARFAESI Act incorporates crucial safeguards for borrowers through Section 17. This section allows any aggrieved person, typically the borrower, to challenge the actions taken by a secured creditor under Section 13(4) by filing an application before the DRT within 45 days. This serves as a vital judicial check, preventing misuse or arbitrary application of recovery measures. The DRTs hold exclusive jurisdiction in such matters, negating the need for the aggrieved party to approach a civil court. The DRT’s jurisdiction is determined by the location of the secured asset, where the cause of action arose, or the bank branch where the borrower’s account is maintained.

Upon receiving an application, the DRT assesses whether the secured creditor adhered to the SARFAESI Act and its rules. If the creditor’s actions are deemed lawful, recovery may proceed. However, if due process was not followed, the DRT can declare the measures invalid, restore possession or management of the secured asset to the borrower, and issue other necessary directions. Section 17 also empowers the DRT to adjudicate on tenancy or leasehold rights claimed by borrowers or third parties in the secured assets. While the statute mandates disposal of such applications within 60 days, this period can be extended up to four months with recorded reasons. If the DRT fails to meet this extended deadline, the aggrieved party may approach the DRAT for expeditious disposal.

Exclusion of Civil Court Jurisdiction: Section 34

Section 34 of the SARFAESI Act imposes a clear judicial bar, stipulating that civil courts lack jurisdiction over matters that DRTs or DRATs are empowered to adjudicate. This provision is designed to prevent parallel proceedings in civil courts, thereby ensuring that the enforcement of security interests is not hindered by conventional litigation. Thus, once a creditor invokes Section 13(4), civil courts are generally precluded from interfering with the SARFAESI enforcement process.

However, this bar is not absolute. The judiciary has clarified that civil courts retain jurisdiction in cases that fall outside the purview of the DRT. If the relief sought does not pertain to Section 13(4) measures or the enforcement of a security interest, civil courts can still entertain such claims.

The Interplay of Sections 17 and 34 and Judicial Interpretations

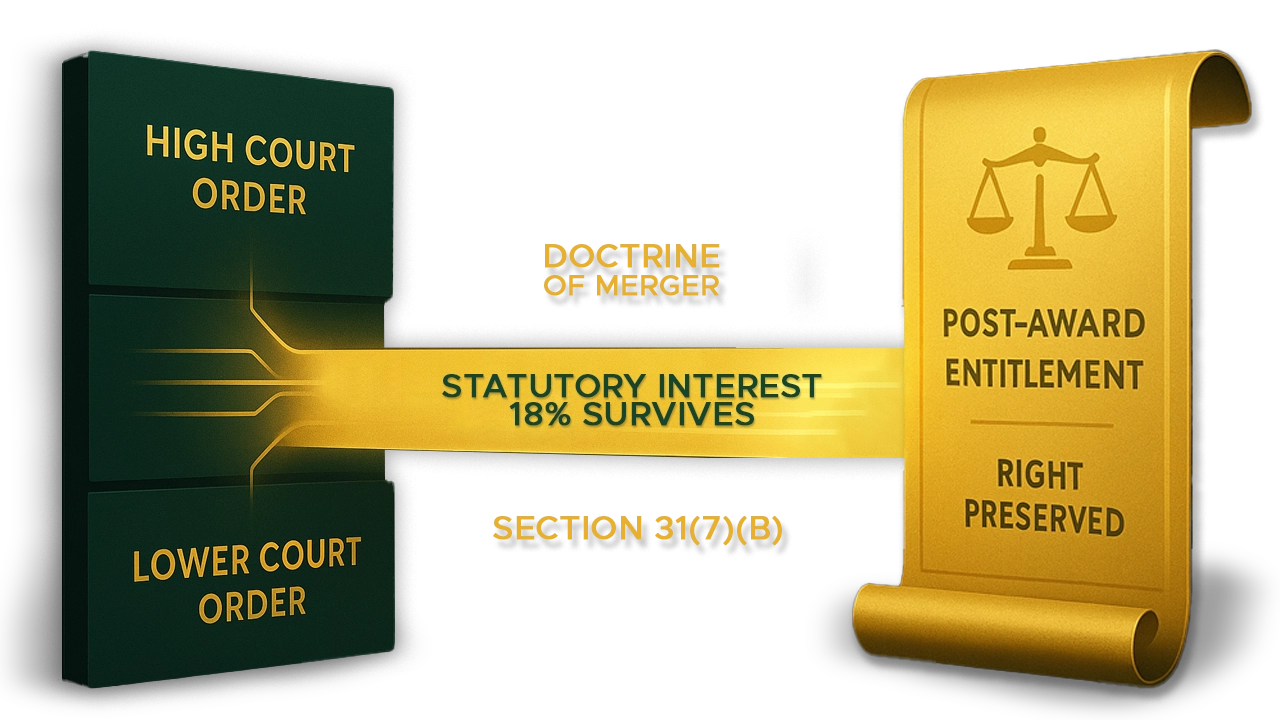

The relationship between Sections 17 and 34 has been a subject of extensive judicial interpretation, aiming to delineate matters for DRT adjudication from those falling under civil court jurisdiction. Section 17 provides a specific remedy for those aggrieved by actions under Section 13(4), allowing them to seek redress from the DRT, which examines the legality of the secured creditor’s actions. Section 34, conversely, bars civil courts from entertaining suits where the DRT or Appellate Tribunal has the power to adjudicate, aiming to expedite SARFAESI disputes.

Courts have consistently maintained that this bar is not absolute; civil court jurisdiction is ousted only to the extent that the DRT is competent to adjudicate a matter under the SARFAESI Act. Where a dispute falls outside the DRT’s scope, civil courts retain jurisdiction under Section 9 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

Key Judicial Interpretations

In Mardia Chemicals Ltd. and others v. Union of India and others2, Supreme Court held that the bar on civil courts applies to matters that may be taken cognizance of by the DRT, in addition to those where measures under Section 13(4) have already been taken. The Court also highlighted that the SARFAESI Act was enacted to address the significant amount of unrecovered dues and the lengthy recovery process through traditional courts. However, a key exception carved out allows civil courts to intervene if the action of secured creditors is fraudulent.

The Delhi High Court, in Shakun Batra & Anr. vs. Kotak Mahindra Bank & Ors3., referenced the Mardia Chemicals Ltd. case, noting that a “mere raising of a bald plea of fraud is not sufficient to bring the case within the exception” for civil court jurisdiction. This implies that for a civil court to assume jurisdiction based on fraud, the allegation must be substantiated beyond a mere claim.

In Bank of Baroda v. Gopal Shriram Panda & Anr4., the High Court of Bombay considered whether the jurisdiction of a Civil Court to decide all civil matters, excluding those triable by the DRT under Section 17 of the Securitisation Act, in relation to the enforcement of security interest, was barred. The case underscored the discord in interpretations regarding the extent of the civil court’s jurisdiction versus the DRT’s.

The case of Elsamma and others v. The Kaduthuruthy Urban Co-operative Bank Ltd and others5 dealt with a suit for permanent prohibitory injunction. The court noted that the remedy under Section 17 of the SARFAESI Act cannot be invoked if the dispute relates to a property that is not a secured asset, and in such instances, the civil court’s jurisdiction is not barred.

Allwyn Alloys v. Authorised Officer (SBI)6 noted the Supreme Court rule that once Section 13 proceedings are initiated, all matters concerning the right, title, or interest in the mortgaged property fall under the DRT’s purview, thereby ousting civil court jurisdiction under Section 34.

Similarly, in Madras Petrochem Ltd. v. BIFR & Ors7., It was reiterated that if action has commenced under Section 13, civil courts lose jurisdiction over the mortgaged property, with the appropriate forum becoming the DRT/DRAT under Section 17.

The Supreme Court in Jagdish Singh v. Heeralal & Ors8. explicitly stated that civil courts lack jurisdiction to entertain disputes arising from enforcement actions under Section 13(4). All objections must be addressed via the statutory remedy under Section 17 within the 45-day window to approach the DRT.

In Abhishek Bose and Ors. Vs. IDBI Bank Ltd. and Ors9., a suit was filed to declare a mortgage deed null and void. The court considered that Section 17(1) of the SARFAESI Act is not the remedy when the applicability of the measures itself is in doubt, strengthening the view that only the testing of measures taken under Section 13(4) can be brought before the Tribunal.

The case of Authorised Officer, Indian Overseas Bank and another v. M/s. Ashok Saw Mill10 highlights that the bar of jurisdiction under Section 34 of the SARFAESI Act does not apply if the property is not a secured asset.

Padma Ashok Bhatt Vs. Orbit Corporation Ltd. and others and Robust Hotels Pvt. Ltd. and others11 Vs. EIH Ltd12. and others reinforce that the bar under Section 34 must correlate to the conditions stipulated under the section, and if not met, the civil court’s jurisdiction cannot be ousted.

A nuanced distinction, however, has been established by courts: disputes unrelated to or preceding SARFAESI actions under Section 13(4), such as those concerning title validity or pre-existing sales, are beyond the DRT’s purview and remain within civil courts’ jurisdiction.

This was further clarified in the landmark Supreme Court judgment Central Bank of India & Anr. v. Smt. Prabha Jain & Ors13.. This ruling asserted that while the SARFAESI Act facilitates speedy recovery, it does not empower the DRT to adjudicate disputes involving title or the validity of sale/mortgage deeds unconnected to Section 13(4) measures. The DRT’s jurisdiction under Section 17(3) is confined to examining the legality of creditor actions under Section 13(4). Consequently, reliefs seeking declarations regarding the invalidity of such deeds are outside the DRT’s scope and are not barred by Section 34, thus remaining triable by civil courts under Section 9 of the CPC. The Court also reaffirmed that a plaint cannot be partially rejected under Order VII Rule 11 CPC; if even one relief survives, the entire plaint must be retained and tried on its merits.

Due Diligence Obligations of Bankers Under SARFAESI Act

Before initiating recovery proceedings under the SARFAESI Act, banks and financial institutions must adhere to specific procedural and statutory requirements to ensure transparency, fairness, and legal compliance while safeguarding borrower rights.

- Preliminary Requirements: A demand notice under Section 13(2) must be served, giving the borrower a minimum of 60 days to repay. This notice must clearly state the total amount due, identify the secured assets to be enforced, and inform the borrower of their right to object. Crucially, the borrower’s account must be classified as a Non-Performing Asset (NPA) according to RBI guidelines before any action, including issuing the Section 13(2) notice.

- Consideration of Borrower’s Representation: If the borrower responds to the Section 13(2) notice with objections, the secured creditor is obligated by Section 13(3A) to consider it. If the representation is deemed unacceptable, reasons for non-acceptance must be recorded and communicated to the borrower within 15 days, upholding principles of natural justice.

- Pre-Conditions for Section 13(4) Actions: Measures under Section 13(4) can only be taken after the 60-day notice period has elapsed without repayment. Full compliance with statutory preconditions is essential to avoid legal infirmities.

- Compliance with Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002: Upon initiating action under Section 13(4), banks must strictly follow these rules. For instance, for immovable property, a possession notice must be delivered to the borrower and affixed to the property (Rule 8(1)). This notice must also be published in two newspapers, one in the vernacular language (Rule 8(2)). Before selling the asset, the bank must obtain a valuation from an approved valuer and fix a reserve price (Rule 8(5)), and a 30-day sale notice must be issued to the borrower and published appropriately (Rule 8(6)). Non-compliance with these mandatory rules can invalidate the enforcement action.

- Borrower’s Right to Approach DRT (Section 17): As per Section 17(1), once a bank takes measures under Section 13(4), the borrower has 45 days to approach the DRT. Thus, banks must ensure all actions are legally compliant and justifiable before the DRT.

- Consent in Multi-Creditor Situations (Section 13(9)): In cases with multiple secured creditors, Section 13(9) mandates that no action under Section 13(4) can be taken unless creditors holding at least 60% in value of the outstanding amount consent to the proposed measures. The initiating bank must secure this approval from other lenders before proceeding.

Conclusion

The SARFAESI Act orchestrates a delicate balance: empowering banks to efficiently recover debts while simultaneously safeguarding borrowers’ rights. While Sections 17 and 34 establish a framework for borrowers to challenge bank actions before the DRT, they also judiciously limit civil court interference in recovery proceedings. Crucially, judicial interpretations have clarified that civil suits remain a viable recourse for issues that extend beyond the DRT’s specific jurisdiction. The Act’s ultimate effectiveness is contingent upon banks diligently adhering to procedural formalities, thereby ensuring that enforcement actions are not only fair and transparent but also non-arbitrary. By upholding these principles, banks can effectively leverage the Act’s benefits, fostering both financial stability and due process within the Indian legal landscape.

Citations

- Debt Recovery Tribunal

- Mardia Chemicals Ltd. and others v. Union of India and others (2004) 4 SCC 311

- Shakun Batra & Anr. vs. Kotak Mahindra Bank & Ors. CS (OS) NO. 451/2021

- Bank of Baroda v. Gopal Shriram Panda & Anr. Civil Revision Application No. 29/2011

- Elsamma and others v. The Kaduthuruthy Urban Co-operative Bank Ltd and others AIR 2019 Ker 23

- Allwyn Alloys v. Authorised Officer (SBI) AIR 2018 SUPREME COURT 2721

- Madras Petrochem Ltd. v. BIFR & Ors. AIR 2016 SUPREME COURT 898

- Jagdish Singh v. Heeralal & Ors AIR 2014 SUPREME COURT 371

- Abhishek Bose and Ors. Vs. IDBI Bank Ltd. and Ors MANU/WB/0895/201 (para 41)

- Indian Overseas Bank and another v. M/s. Ashok Saw Mill MANU/SC/1219/2009

- Padma Ashok Bhatt Vs. Orbit Corporation Ltd. and others MANU/MH/1663/2017

- Robust Hotels Pvt. Ltd. and others Vs. EIH Ltd. MANU/SC/1559/2016

- Central Bank of India & Anr. v. Smt. Prabha Jain & Ors.. 2025 INSC 95

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla