Introduction

The realm of financial crime is a complex web, and at its heart lies the formidable challenge of combating money laundering. Imagine a sophisticated operation where funds obtained through illicit means – perhaps a large-scale drug trafficking ring or a massive financial fraud – are meticulously routed through a labyrinth of transactions, shell companies, and international accounts, all with the singular aim of making the “dirty” money appear legitimate.This process, known as money laundering, is precisely what the PMLA1 in India seeks to dismantle.

However, a critical question consistently surfaces within this intricate legal framework: what happens when the very foundation of a money laundering case—the “predicate” offence that generated the illicit funds—collapses? Does a discharge or acquittal in the predicate offence automatically render the PMLA proceedings invalid? This is the high-stakes legal conundrum currently before the Supreme Court of India.

A bench comprising Justices Surya Kant and Joymalya Bagchi is poised to deliberate on this pivotal issue. Their consideration stems from a challenge to a Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh High Court order in Niket Kansal Vs. Union of India through Enforcement Directorate2, which boldly asserted that a discharge in the predicate offence does not automatically invalidate proceedings initiated under the PMLA. This assertion signifies a crucial divergence in legal interpretation, potentially reshaping the landscape of anti-money laundering enforcement in India. This article will delve into a detailed analysis of the judicial precedents underpinning the Jammu and Kashmir judgment and explore the far-reaching implications of the Supreme Court’s impending decision on the autonomy and scope of PMLA proceedings.

The issue at hand, as the Jammu and Kashmir High Court emphasized, transcends mere factual determination. It zeroes in on a fundamental legal question: can a summons issued to a petitioner be annulled solely on the basis of their discharge in the predicate offence? The legal landscape, as illuminated by a series of significant pronouncements, suggests otherwise. It’s a well-established principle that a discharge in the predicate offence does not, in itself, inhibit authorities from pursuing additional legal actions or enforcement measures, including the issuance of a summons. After all, the issuance of a summons constitutes a separate procedural action, not inherently invalidated by a discharge in a different, albeit related, case. The underlying rationale is clear: the legal provisions governing summons are designed to uphold the integrity of the legal process, and courts are generally hesitant to intervene unless there are unequivocal and compelling grounds. Consequently, authorities retain the right to execute such summons, as these actions are regulated by distinct legal principles unaffected by the outcome of the underlying predicate offence.

The High court relied upon the Hon’ble Supreme Court decisive ruling in Director, Enforcement Directorate & Anr v. Vilelie Khamo3, decided on December 19, 2024. In this landmark judgment, the apex court annulled a High Court’s order that had quashed a summons merely because the respondent had been discharged in the predicate offence. The Supreme Court succinctly stated: “We are limiting ourselves to the question of law. What has been issued to the respondent is merely a summons. Simply because he has been discharged in the predicate offence, a Court cannot quash the summons. The questions as to whether the respondent would be arrayed as an accused or not, is a matter which has to be decided at a later stage.” This pronouncement reinforces the independent nature of PMLA proceedings, particularly at the investigative stage.

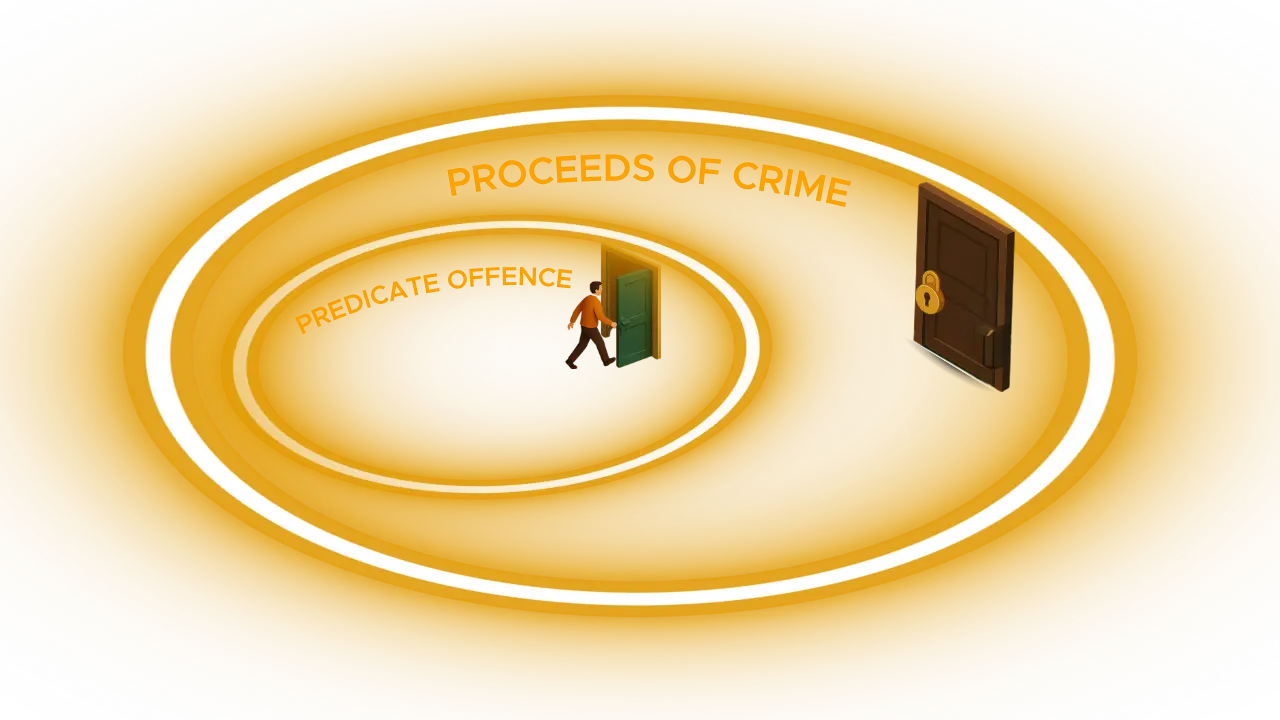

Further bolstering this perspective the High court relied upon the seminal Vijay Madanlal Choudhary4case , where the Hon’ble Supreme Court unequivocally clarified that the offence of money laundering, as defined under Section 3 of the PMLA, is an independent offence. It pertains to the process or activity connected with “proceeds of crime” derived from a scheduled offence. What does this mean for the connection between the two? The Court elaborated: “Thus, involvement in any one of such processes or activity connected with the proceeds of crime would constitute an offence of money laundering. This offence otherwise has nothing to do with the criminal activity relating to a scheduled offence — except the proceeds of crime derived or obtained as a result of that crime.” This crucial distinction implies that even if the scheduled offence is tried under the Indian Penal Code or other specific acts, money laundering is prosecuted separately under the PMLA. The relevant date for the offence of money laundering isn’t when the predicate offence was committed, but rather when an individual “indulges in the process or activity connected with such proceeds of crime.”

This critical separation was further solidified in Pavana Dibbur v. The Directorate of Enforcement5 . The Supreme Court clarified that a person accused under Section 3 of the PMLA need not necessarily be an accused in the scheduled offence. Intriguingly, a person “unconnected to the scheduled offence but knowingly assisting in the concealment of the proceeds of crime, can be held guilty of committing an offence under Section 3 of the PMLA.” This raises a pertinent question: if an individual not directly involved in the predicate crime can be prosecuted for money laundering, why would a discharge in the predicate offence automatically halt a PMLA investigation? The Court did clarify that if the prosecution for the scheduled offence “ends in the acquittal of all the accused or discharge of all the accused or the proceedings of the scheduled offence are quashed in its entirety, the scheduled offence will not exist, and therefore, no one can be prosecuted for the offence punishable under Section 3 of the PMLA as there will not be any proceeds of crime.” However, it is the continuing existence of the scheduled offence and the “proceeds of crime” that remains key, not necessarily the conviction of a particular individual in the predicate offence.

The Enforcement Directorate’s authority to summon individuals under Section 50 of the PMLA is primarily for the acquisition of factual evidence. A summons does not inherently brand someone as an accused; rather, it indicates they may possess information or documents pertinent to the investigation. Therefore, a petitioner’s discharge in the predicate offence does not automatically constitute a legitimate ground for nullifying such a summons. These procedural safeguards are essential for preserving the integrity of the investigative and adjudicatory processes, compelling individuals to cooperate in the accurate collection of evidence.

Adding another layer to this complex legal tapestry, in the present case, the order of discharge in the predicate offence has itself been formally contested by the respondents, with a criminal revision6 currently pending before the Court. The outcome of this revision will effectively settle the issues relating to the legitimacy of the discharge, further underscoring that the matter is far from a closed chapter.

Ultimately, the validity of a summons, as a procedural action within the Court’s jurisdiction, remains intact despite a respondent’s discharge in the predicate offence. The Vijay Madanlal Choudhary judgment, binding on all subordinate courts, emphasizes that the offence of money laundering under the PMLA is distinct from the scheduled offence. While factually linked, the two proceedings are legally independent and governed separately. ECIR7 under the PMLA is not merely an extension of the FIR for the predicate offence; it’s a distinct investigation into money laundering. Therefore, a discharge in the predicate offence may influence PMLA procedures but cannot be regarded as an automatic or definitive basis for nullifying the ECIR. A mechanical or blanket approach would contradict the very objectives of the PMLA, potentially undermining its crucial role in preventing and prosecuting financial crimes.

Conclusion

The current legal discourse, illuminated by the Jammu and Kashmir High Court’s resolute stance and fortified by Supreme Court pronouncements, points towards a clear trajectory for the future of PMLA proceedings. The Supreme Court, in taking up this challenge, is likely to re-emphasize the distinct and independent nature of the offence of money laundering under the PMLA, separate from its predicate offence. This isn’t merely a procedural nicety; it’s a fundamental recognition of the PMLA’s unique mandate – to dismantle the elaborate machinery of financial crime, not just prosecute its initial illicit act.

The ramifications of such a reaffirmation would be significant. It would empower the Enforcement Directorate to continue its investigations and issue summons, even when the underlying predicate offence faces a discharge or quashing, provided there is a tangible link to “proceeds of crime.” This stance prioritizes the pursuit of illicit wealth and its laundering, rather than making PMLA cases wholly contingent on the successful conviction in the predicate offence. It underscores the legislative intent to view money laundering as a continuing offence, a pervasive activity that thrives as long as tainted assets are concealed, possessed, or projected as untainted. This would undoubtedly streamline and strengthen the investigative arm of the PMLA, ensuring that those who facilitate the legitimization of ill-gotten gains do not escape scrutiny simply because a primary charge might not hold up.

However, even with such clarity, new questions may inevitably arise. While the Supreme Court might affirm the independence of PMLA proceedings at the summons and investigative stages, what about at the stage of trial and conviction? If, ultimately, a person is fully acquitted or discharged from the predicate offence, and no “proceeds of crime” can be definitively traced or established to have originated from a criminal activity, could the PMLA proceedings still lead to a conviction for money laundering? Or would the very foundation of “proceeds of crime” crumble, rendering the PMLA case unsustainable? The delicate balance between ensuring effective anti-money laundering measures and safeguarding individual liberty against indefinite pursuit remains a critical area, potentially prompting further judicial scrutiny in the years to come. The Supreme Court’s impending decision, while offering crucial guidance, might well pave the way for a deeper examination of these nuanced intersections in India’s fight against financial crime.

Citations

- Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002

- Niket Kansal Vs. Union of India through Enforcement Directorate CRM(M) No. 140/2025

- Director, Enforcement Directorate & Anr v. Vilelie Khamo (SLP [CRL.] NO. 15189/2024)

- Vijay Madanlal Choudhary Special Leave Petition (Criminal) No. 4634 Of 2014

- Pavana Dibbur v. The Directorate of Enforcement (2023 INSC 1029)

- Niket Kansal Versus Union Of India, Slp(Crl) No. 8814/2025

- The Enforcement Case Information Report

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit