Introduction

Imagine a dispute brewing for years, discussions stretching into endless negotiations, and then, suddenly, one party decides to invoke arbitration. How long do they have? Can they wait indefinitely, hoping for a miracle resolution, or does the law, like a diligent timekeeper, step in to ensure disputes don’t fester forever? This very question lies at the heart of the “law of limitation” in India, a legal principle beautifully encapsulated by the Latin maxim: “vigilantibus non dormientibus jura subveniunt” – the law assists the vigilant, not those who sleep over their rights.

This principle, enshrined in the Limitation Act of 1963, acts as a guardian, preventing parties from being subjected to an indefinite period of liability. Just as there are different deadlines for filing your taxes or renewing your passport, various legal actions have prescribed periods within which they must be initiated. While the Limitation Act provides a general framework, special laws often carve out their own specific timelines, and Arbitration Act1 is a prime example of legislation striving for faster dispute resolution.

Yet, despite the Arbitration Act’s emphasis on speed, a curious gap has persisted: it has never explicitly defined a limitation period for arbitration petitions under Section 11 of the Arbitration Act, which deals with the appointment of an Arbitral Tribunal. This legislative silence has led to a fascinating journey through judicial pronouncements, with Indian courts stepping in to fill the void and shape the evolving jurisprudence of limitation for arbitration petitions.

The Judicial Compass: Charting the Course of Limitation

For years, the Indian judiciary has acted as the guiding star, clarifying that Section 11 of the Arbitration Act, in the absence of a specific provision, would be governed by the residual Article 137 of the First Schedule of the Limitation Act. This means a party seeking to invoke arbitration generally had a limitation period of 3 years to file a Section 11 arbitration petition. This period would typically commence from the date the opposite party failed to make an appointment as per the agreed procedure. For instance, if a contract stipulated a 30-day period for appointing an arbitrator, and that period passed without an appointment, the clock for the Section 11 petition would start ticking. Similarly, if the opposing party explicitly refused to comply with an arbitration notice, another 3-year period would begin from the date of such refusal to seek the arbitrator’s appointment. This position was solidified in cases like BSNL v. Nortel Networks India (P) Ltd2..

However, the Supreme Court, in Arif Azim Co. Ltd. v. Aptech Ltd3. has astutely observed that such an extended limitation period runs contrary to the very spirit of expeditious resolution, particularly in commercial disputes. The court suggested that the legislature should step in and prescribe a more specific, shorter period. This proactive judicial stance underlines a broader concern: if applications under Section 11 remain pending for years, it fundamentally defeats the purpose of the Arbitration Act, as highlighted in Shree Vishnu Constructions v. Military Engg. Service4.

More recently, a significant shift has occurred in judicial thinking regarding the referral stage. Courts have emphasized that at this initial juncture, they should refrain from delving into the merits or limitations of the underlying claims. Their inquiry should be confined to determining whether the Section 11 petition itself has been filed within the 3-year limitation period. This approach, as seen in SBI General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Krish Spg5. (2024 SCC OnLine SC 1754), is crucial for preserving the autonomy and efficacy of the arbitration process. Why is this so vital? Because parties do not have the right to appeal against an order passed by the referral court under Section 11, whether it appoints or refuses to appoint an arbitrator. If the referral court were to pre-emptively assess the claims’ merits and reject the application, it could leave the claimant without any further recourse for the adjudication of their claims, as underscored in Aslam Ismail Khan Deshmukh v. ASAP Fluids (P) Ltd6.. This predicament has even led the Supreme Court to suggest an amendment to Section 37 of the Arbitration Act, proposing the addition of Section 37(aa) to allow appeals against orders refusing the appointment of an arbitrator, a recommendation echoed in Pravin Electricals (P) Ltd. v. Galaxy Infra and Engg. (P) Ltd7..

The Legislature’s Response: A Shorter Deadline on the Horizon?

Responding to these judicial pronouncements and the palpable need for a more definitive and shorter timeline, the Draft Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024 (Amendment Bill) has proposed a significant change. It suggests that parties must file Section 11 arbitration petitions for the appointment of an arbitrator within a strict period of 60 daysfrom the failure or refusal of the opposite party to make the appointment.

This proposed 60-day period undoubtedly aims to inject greater speed and predictability into the Indian arbitration landscape. However, is such a tight deadline a double-edged sword? There’s a genuine concern that the fear of missing this stringent deadline might compel parties to rush into arbitration prematurely, potentially bypassing crucial negotiation and settlement attempts.

This brings us to a fundamental aspect of limitation law: the discretion often afforded to courts to entertain time-barred claims, exclude certain periods, or condone delays in reasonable circumstances. While the Amendment Bill aims for swiftness, it currently appears to be silent on these crucial aspects for Section 11 petitions.

Should the Amendment Bill also provide for circumstances where courts can still entertain time-barred petitions, perhaps by excluding time spent in genuine settlement efforts or in pursuing remedies before incorrect forums? This balance between urgency and fairness is paramount to ensure arbitration remains both efficient and effective.

Decoding Exclusions: When the Clock Pauses

Given that the provisions of the Limitation Act have been deemed applicable to Section 11 arbitration petitions, it becomes essential to understand when parties might be able to benefit from the exclusion of time spent in good faith pursuing proceedings before courts lacking jurisdiction. Section 14 of the Limitation Act is the key here, providing for the exclusion of time spent prosecuting bona fide proceedings in a court without jurisdiction while computing the limitation period for any suit or application.

Indian courts have deliberated extensively on these exclusions in the context of arbitration petitions:

- Negotiations – A Delicate Balance: While the Supreme Court, in B and T AG v. Ministry of Defence8, held that subsequent negotiations after the cause of action generally won’t postpone the limitation period, it also provided a crucial caveat. If the entire history of negotiations is meticulously documented and clearly demonstrates a “breaking point” where any reasonable party would have abandoned settlement efforts, then such genuine negotiations are liable to be excluded. The Delhi High Court, in Blooming Orchid v. FP Life Education Foundation9 , reinforced this, excluding a period of bona fide email exchanges evidencing settlement attempts, provided the negotiation history was well-documented.

- Moratorium Period of a Corporate Debtor – A Protective Shield: IBC10 introduces a “moratorium” period during which legal proceedings against a corporate debtor are typically halted. The Supreme Court, in New Delhi Municipal Council v. Minosha India Ltd., decisively ruled that under Section 60(6) of the IBC, the entire period during which a moratorium was in operation must be excluded when computing the limitation for a Section 11 arbitration petition filed by the corporate debtor. This ensures that a debtor’s rights aren’t prejudiced by insolvency proceedings.

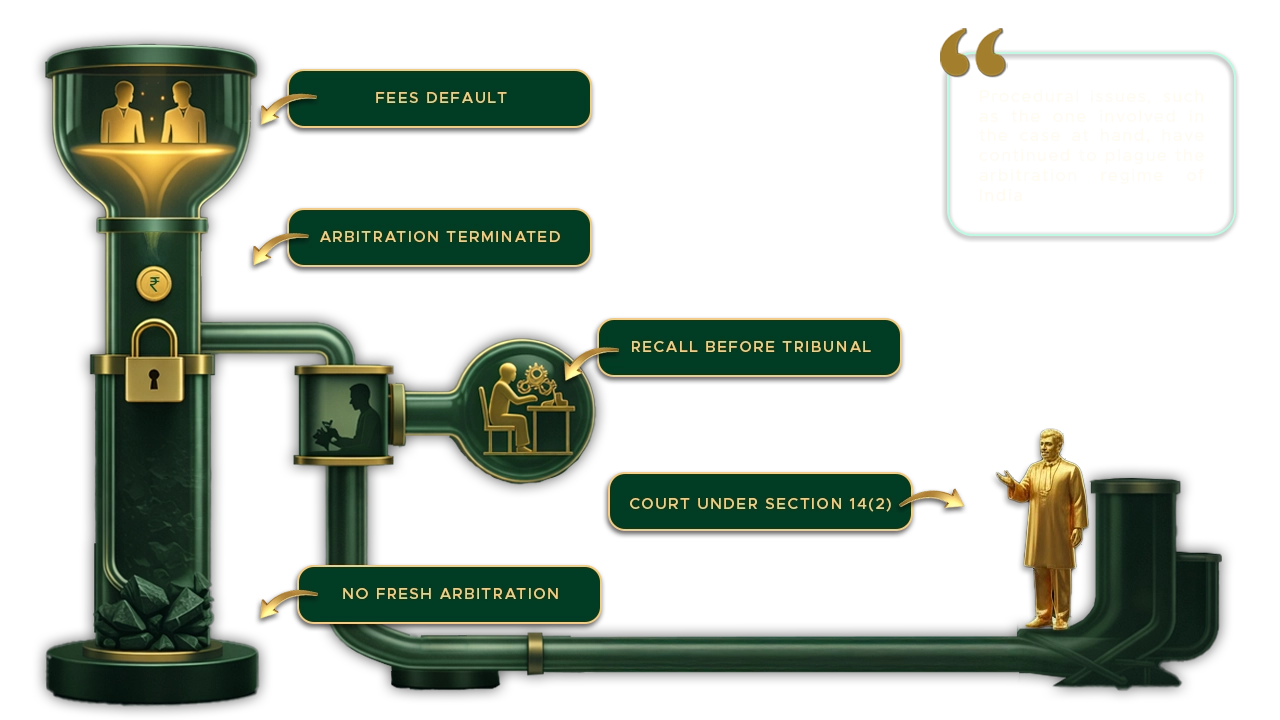

- IBC Proceedings – Different Reliefs, Different Rules: A nuanced distinction arises when considering time spent in IBC proceedings. In HPCL Bio-Fuels Ltd. v. Shahaji Bhanudas Bhad11, the Supreme Court held that a Section 11 arbitration petition is an application governed by Section 14(2) of the Limitation Act. However, it clarified that for the benefit of exclusion, the relief sought must be the same. Since IBC proceedings aim for insolvency initiation and corporate debtor rehabilitation, while a Section 11 petition seeks an arbitrator’s appointment for contractual dispute adjudication, the reliefs are different. Therefore, the time spent in insolvency proceedings cannot be excluded from the limitation period for a Section 11 arbitration petition.

- Commercial Court Proceedings – A Seamless Transition: What if a party mistakenly pursues a commercial suit instead of arbitration? The Delhi High Court, in JKR Techno Engineers (P) Ltd. v. JMD Ltd12. , provided clarity. If a commercial suit is disposed of under Section 8 of the Arbitration Act for referral to arbitration, the respondent cannot subsequently argue that the suit was barred by limitation. This means the time genuinely spent in bona fide court proceedings lacking jurisdiction before the commercial court will be excluded when calculating the limitation for a Section 11 arbitration petition.

Conclusion

The journey of India’s arbitration law, marked by a proactive judiciary and a responsive legislature, underscores a persistent quest for efficiency and clarity. The proposed Draft Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024, with its bold move to a 60-day limitation period for Section 11 petitions, embodies this ambition. It signals a decisive shift from a judicially interpreted, somewhat protracted timeline, to a statutorily mandated, significantly shorter window, reflecting an intent to truly align India’s arbitration landscape with global best practices that prioritize swift dispute resolution. This proposed change, coupled with the inclusion of an appellate mechanism for refusal to appoint an arbitrator, demonstrates a commitment to streamline processes and foster greater confidence in the arbitral system.

However, as with any significant legislative overhaul, the real implications will unfold in practice. Will the strict 60-day period truly foster a more “vigilant” approach, compelling parties to act swiftly and genuinely engage in settlement discussions, or will it, as some fear, create an environment of rushed arbitration, where the pressure of the deadline overshadows the opportunity for meaningful negotiation? This proposed tightness of the clock raises pertinent questions about equitable access to justice, particularly for parties who may face unforeseen circumstances or genuinely believe in extended good-faith settlement efforts. Will courts, in the absence of explicit provisions within the Amendment Bill, continue to leverage the principles of exclusion under the Limitation Act, especially Section 14, to condone delays or exclude time spent in bona fide, albeit misdirected, legal pursuits?

The path ahead remains intriguing. While the proposed amendments aim to iron out ambiguities and accelerate the arbitral process, the lack of a similarly stringent timeline for the disposal of Section 11 applications by courts presents a potential bottleneck, threatening to undermine the very speed it seeks to achieve. Will the legislature address this asymmetry, ensuring that the burden of promptness is shared not just by the parties but also by the judicial machinery tasked with facilitating arbitration? Ultimately, the success of these reforms will hinge on striking a delicate balance: promoting expeditious resolution without inadvertently sacrificing fairness, fostering institutional arbitration without stifling genuine pre-arbitration conciliation, and ensuring that the pursuit of efficiency remains rooted in the overarching principle of justice.

Citations

- The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

- BSNL v. Nortel Networks India (P) Ltd.(2021) 5 SCC 738

- Arif Azim Co. Ltd. v. Aptech Ltd.(2024) 5 SCC 313

- Shree Vishnu Constructions v. Military Engg. Service (2023) 8 SCC 329

- SBI General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Krish Spg. (2024 SCC OnLine SC 1754)

- Aslam Ismail Khan Deshmukh v. ASAP Fluids (P) Ltd. (2025) 1 SCC 502

- Pravin Electricals (P) Ltd. v. Galaxy Infra and Engg. (P) Ltd. (2021) 5 SCC 671

- B and T AG v. Ministry of Defence (2024) 5 SCC 358

- Blooming Orchid v. FP Life Education Foundation (2024 SCC OnLine Del 3691

- The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016

- HPCL Bio-Fuels Ltd. v. Shahaji Bhanudas Bhad (2024 SCC OnLine SC 3190)

- JKR Techno Engineers (P) Ltd. v. JMD Ltd.# (2024 SCC OnLine Del 7809)

Expositor(S): Adv. Anuja Pandit