Introduction

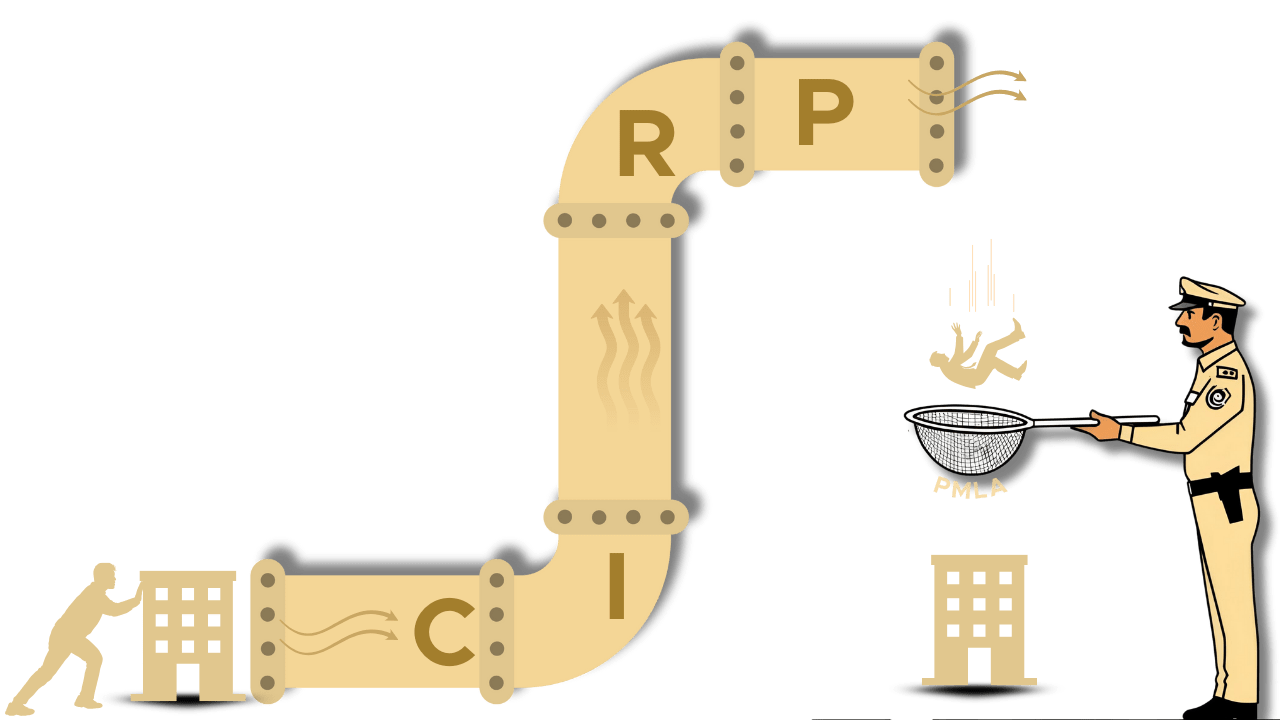

In a significant ruling that adds a new dimension to corporate insolvency law, the Madras High Court recently directed1 the IBBI2 to consider granting sanction for the prosecution of a RP3. The case involves serious allegations of mismanagement of a company’s funds during the resolution process, and the core of the court’s decision hinges on a crucial question: is a Resolution Professional a ‘public servant’ under the PC Act4?

This question has created a judicial split, with different High Courts holding opposing views. The recent Madras High Court judgment, delivered by Justice Bharatha Chakravarthy, unequivocally states that a Resolution Professional qualifies as a public servant. This conclusion was based on the court’s interpretation of key sections from the PC Act’s definition of a public servant.

Let’s break down these definitions:

- Section 2(c)(v): This part of the Act defines a public servant as “any person authorised by a court of justice to perform any duty, in connection with the administration of justice, including a liquidator, receiver or commissioner appointed by such court.” The Madras High Court reasoned that an RP, appointed by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT)—which functions as a court of justice for corporate matters—falls squarely within this category.

- Section 2(c)(vi): This section includes “any arbitrator or other person to whom any cause or matter has been referred for decision or report by a court of justice or by a competent public authority.” The court noted that an RP is required to submit a report to the NCLT and the Committee of Creditors, thus fulfilling this definition as well.

- Section 2(c)(viii): This is a broad, catch-all provision that includes “any person who holds an office by virtue of which he is authorised or required to perform any public duty.” The court held that an RP’s role in the insolvency process, which involves managing a company’s assets and resolving its financial health, is inherently a public duty.

The case that led to this ruling was initiated by Anil Kumar Ojha, the former Managing Director of M/s. S.L.O Industries Limited. Ojha sought a CBI investigation after a liquidator, appointed when the company went into liquidation, discovered a significant discrepancy of ₹625.25 crore in the inventory. The RP argued that the definition of a public servant should not be expanded to include them and that the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) already protects their actions taken in good faith. The IBBI, on the other hand, was hesitant to grant sanction, citing a pending Supreme Court case that would definitively settle the issue.

Despite the pending Supreme Court ruling, the Madras High Court asserted that delaying the matter would result in the “golden time for investigation and prosecution” being lost. The court held that even though an RP’s role is largely administrative and subject to the Committee of Creditors’ supervision, their duties are performed “in the course of the administration of justice,” and therefore, they are not exempt from the PC Act.

This stance aligns with a recent Jharkhand High Court ruling in Sanjay Kumar Agarwal vs. Union of India5. In this case, Justice Gautam Kumar Choudhary’s bench also held that a Resolution Professional is a public servant under Sections 2(c)(v) and (viii) of the PC Act. The court noted that the PC Act’s definition is “very wide and expansive” and not limited to government employees. The ruling came after a Resolution Professional was allegedly caught red-handed accepting a bribe. The court rejected the petitioner’s argument that they were not a public servant and therefore immune from prosecution under the PC Act.

But what about the opposing view? The legal tussle over this definition is best highlighted by a ruling from the Delhi High Court. The Delhi High Court, in the case of Dr. Arun Mohan vs. Central Bureau of Investigation6, held that Resolution Professionals are not public servants under the PC Act. This judgment was a key reason for the IBBI’s initial reluctance to grant sanction in the Madras High Court case. The Delhi High Court reasoned that the principle of ‘ejusdem generis’—where a general term is interpreted in light of the specific terms that precede it—should be applied to Section 2(c)(v). According to this view, since the section lists specific judicial appointees like a “liquidator, receiver or commissioner,” an RP, who doesn’t have the power to dispose of assets in the same manner, shouldn’t be included.

Additionally, the Delhi High Court noted that an RP’s function is more “administrative” and “purely recommendatory,” unlike a liquidator who has a more definitive role in asset management. This argument was also put forth by the Resolution Professional in the Madras High Court case, who referenced Supreme Court judgments such as Swiss Ribbons Private Ltd. Vs. Union of India7 and Arcelor Mittal India Private Ltd. Vs. Satish Kumar Gupta and Ors8. to argue that an RP’s role is administrative and designed to serve “private interests.”

However, both the Madras and Jharkhand High Courts have respectfully disagreed with this interpretation. The Madras High Court rejected the application of ‘ejusdem generis’, stating that the wording of the section is inclusive and broad enough to encompass any duty related to the “administration of justice.” The court also dismissed the argument that an RP’s role is merely administrative, asserting that this does not preclude them from being a public servant, as long as the work is performed in the course of administering justice.

The ongoing judicial debate underscores the evolving legal landscape surrounding the IBC9. The conflicting rulings from different High Courts on such a fundamental issue demonstrate the need for a definitive pronouncement from the Supreme Court. The top court has already clubbed the appeals from both the Delhi and Jharkhand High Court judgments. The outcome of this legal battle will have far-reaching implications, not only for the accountability of Resolution Professionals but also for the integrity of the entire insolvency resolution process in India.

The question remains: will the Supreme Court follow the expansive, functional approach adopted by the Madras and Jharkhand High Courts, or will it uphold the more restrictive interpretation of the Delhi High Court? The final verdict will determine whether Resolution Professionals, a cornerstone of India’s corporate insolvency framework, will be held accountable as ‘public servants’ and subject to the full rigour of the Prevention of Corruption Act.

Conclusion

The divergent rulings from the Madras, Jharkhand, and Delhi High Courts on the status of Resolution Professionals have created a significant legal void that only the Supreme Court can fill. This judicial split has thrown the accountability of RPs into a state of uncertainty, creating a precarious situation for both the professionals and the stakeholders they serve. On one hand, classifying RPs as public servants could enhance transparency and deter corruption, which are crucial for maintaining the integrity of the IBC process. On the other, it could expose them to frivolous and vexatious litigation, which might discourage competent professionals from taking on complex insolvency cases, thereby hindering the very purpose of the IBC.

The future ramifications of the Supreme Court’s decision will be profound and far-reaching. If RPs are deemed public servants, it will introduce a new layer of oversight and accountability, making them subject to prosecution under the Prevention of Corruption Act for offenses like bribery and criminal misconduct. This could significantly reshape the insolvency profession, requiring RPs to operate with a heightened level of caution and adherence to public service standards. The IBBI will have a more potent tool to ensure ethical conduct, as it would be empowered to grant sanction for prosecution. This would be a pivotal step towards fortifying the IBC’s framework and safeguarding it from malpractice.

However, this paradigm shift also raises critical questions that need to be addressed. Will the fear of being labeled a public servant lead to a shortage of qualified RPs, particularly for high-stakes cases? How will this classification impact the speed and efficiency of the resolution process, which is a cornerstone of the IBC? Furthermore, will the inclusion of RPs under the PC Act open the floodgates for disgruntled debtors or creditors to file false complaints, using the law as a weapon to derail the insolvency proceedings? The answers to these questions will be instrumental in defining the future of corporate insolvency in India, ensuring a balance between accountability and the operational autonomy required for a successful resolution. The Supreme Court’s upcoming judgment is not merely a legal pronouncement; it is a policy-shaping decision that will either reinforce the IBC as a robust, corruption-resistant framework or introduce a new set of challenges to its practical implementation.

Citations

- Anil Kumar OjhaVersus The State Rep by Inspector of Police, CBI ACB,Chennai

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India

- Resolution Professional

- Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

- Sanjay Kumar Agarwal vs. Union of India 2025 SCC OnLine Jhar 1081

- Dr.Arun Mohan Vs. Central Bureau of Investigation in W.P.(Crl).No.544 of 2020

- Swiss Ribbons Private Ltd. Vs. Union of India(2019) 4 SCC 17

- Arcelor Mittal India Private Ltd. Vs. Satish Kumar Gupta and Ors (2019) 2 SCC 1

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code,2016

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit