Introduction

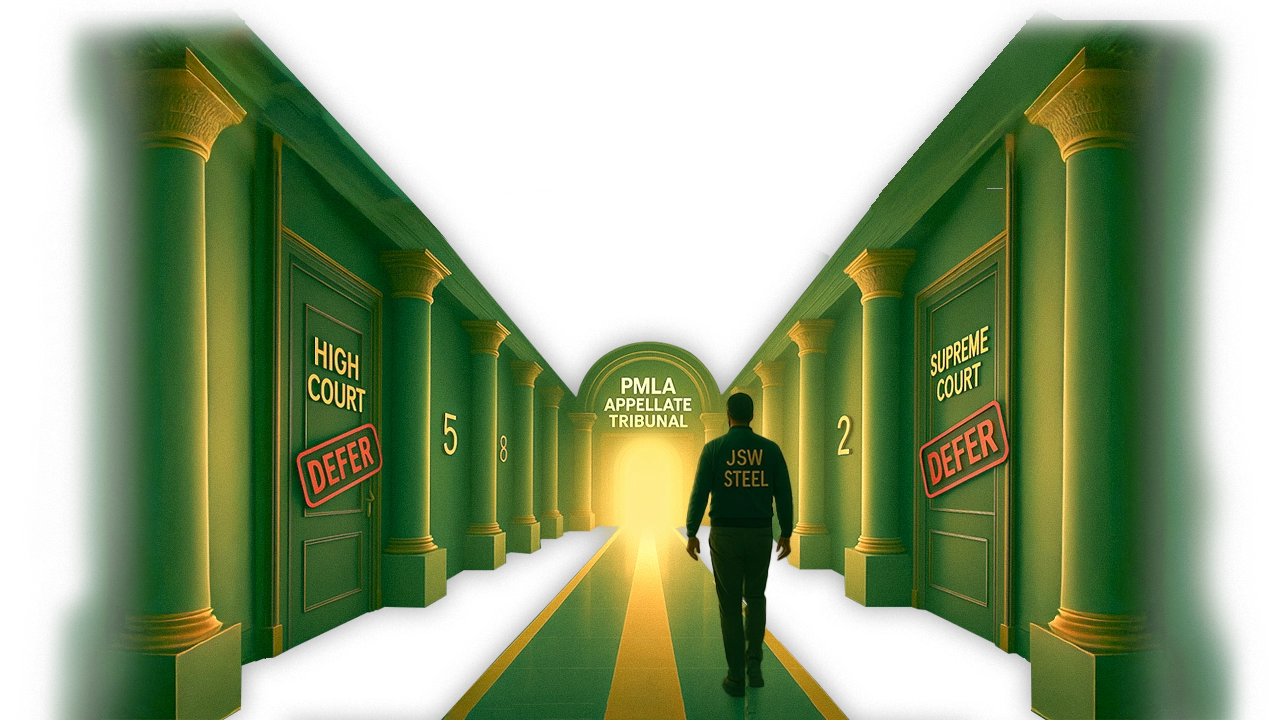

In the intricate landscape of corporate legal battles, one question often looms large: When does a bona fide business transaction become entangled in the web of alleged criminal proceeds, and what recourse does an entity have when a state agency targets its assets? The Supreme Court of India recently addressed such a high-stakes scenario in Jsw Steel Limited Etc.Versus Deputy Director, Directorate Of Enforcement Etc1., refusing to quash ongoing proceedings initiated by the Directorate of Enforcement (ED2) against JSW Steel Limited under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA3), thereby firmly underscoring the supremacy of statutory appellate mechanisms in PMLA cases.

Can a company, once cleared of the main criminal charge, still face the heavy hand of the law under the PMLA? This complex question lies at the heart of the Court’s decision. The legal challenge mounted by JSW Steel rested on a fundamental argument: that with the CBI4 having dropped the charges against the company in the underlying illegal mining case—the “scheduled offence“—the entire prosecution was founded on ‘mere apprehension’. Citing the landmark decision in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary and Others v. Union of India and Others5, JSW Steel contended that the absence of a ‘live scheduled offence’ should nullify the PMLA proceedings, as there could be no ‘proceeds of crime’ and, consequently, no offence under Section 3 PMLA (which defines the offence of money laundering).

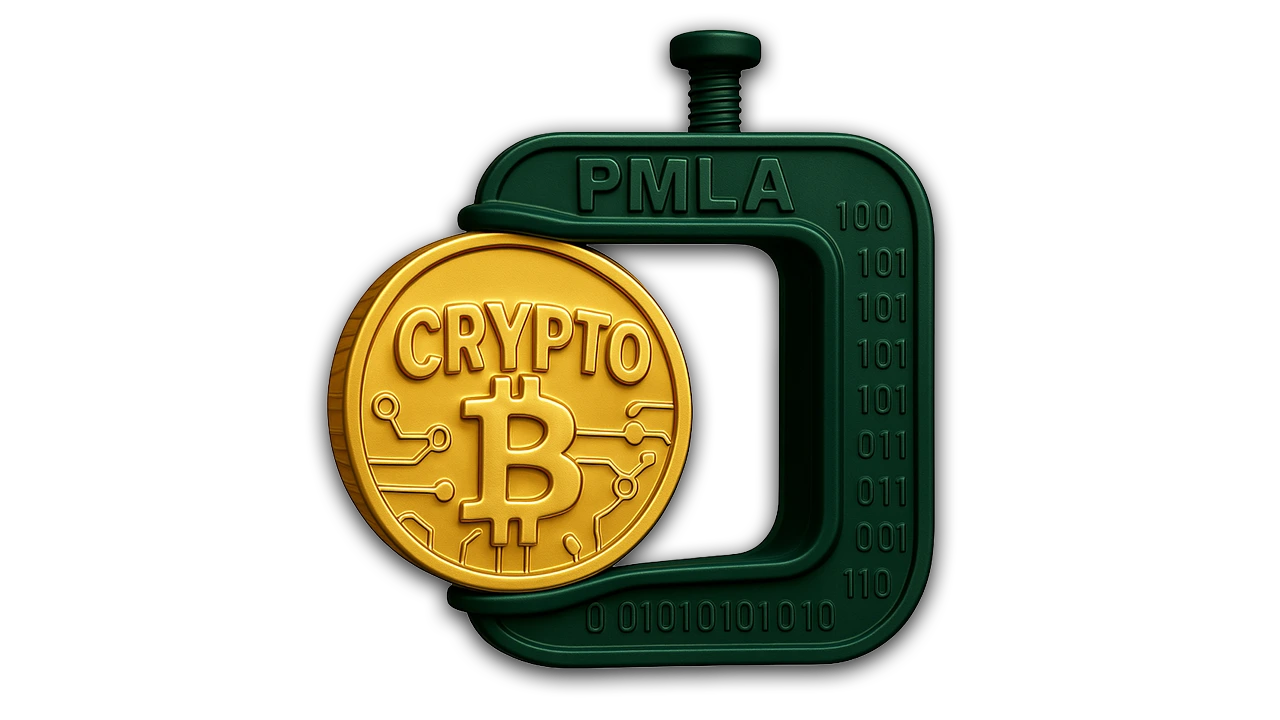

Beyond the scheduled offence, the narrative shifted to the nature of the alleged money laundering itself. The Enforcement Directorate (ED)’s complaint was not based on the original crime, but on the allegation that JSW Steel had wilfully frustrated the Provisional Attachment Orders (PAOs6) by withdrawing ₹33.80 crore from its bank accounts. Was this frustration of attachment itself a crime? JSW Steel’s counsel argued that withdrawals of ₹21.45 crore occurred before the PAO was even communicated, and that subsequent withdrawals during a High Court stay were lawful, demonstrating a lack of mens rea (criminal intent) to project the property as untainted. Furthermore, a crucial technicality was raised: can cash-credit accounts—which essentially represent a drawing limit or an overdraft facility—even be subjected to attachment under Section 5 PMLA? Citing the Bombay High Court in Skytech Rolling Mill Pvt. Ltd. v. Joint Commissioner of State Tax Nodal 1 Raigad Division7, it was stressed that these are not specific ‘property’ in the conventional sense. The ED, however, countered vehemently. Relying on the Supreme Court’s ruling in State of Maharashtra v. Tapas D. Neogy8, they asserted that “bank accounts are indeed “property” under Section 2(1)(v) PMLA” (which defines “property”), and thus a specified quantum can be validly attached. The agency insisted that JSW Steel’s deliberate dissipation of the attached funds and continued possession of ₹16.55 crore of the alleged proceeds constituted a clear and continuing offence under Section 3 of the PMLA.

The judicial focus ultimately converged not on the merits of the arguments, but on the propriety of intervention. The Court noted an undeniable fact: JSW Steel had already invoked its statutory remedy by filing an appeal before the Appellate Tribunal under Section 26 PMLA (which provides for appeals against orders of the Adjudicating Authority). Why bypass this entire self-contained system?

The PMLA, the bench observed, provides a comprehensive and self-contained adjudicatory mechanism: Section 5 governs Provisional Attachment; Section 8 deals with Confirmation by the Adjudicating Authority; and Section 26 establishes the Appellate Tribunal. Referencing established jurisprudence, including Union of India and Another v. Guwahati Carbon Limited9, the Court stressed that its extraordinary or appellate jurisdiction should not ordinarily be exercised when an efficacious alternate remedy is available and actively being pursued. Interfering at this stage would, the Court reasoned, prejudge issues—such as whether the ₹33.80 crore truly constitutes “proceeds of crime” under Section 2(1)(u) PMLA (which defines “proceeds of crime”) or if the withdrawals violated the law—that are squarely within the domain of the Appellate Tribunal.

The Court clarified that the prosecution was not aimed at fastening criminal liability beyond the recovery of the quantified amount. While arguments relying on R.P. Kapur v. State of Punjab10 and State of Haryana and Others v. Bhajan Lal and Others11 were made to quash the prosecution where allegations, taken at face value, do not constitute an offence, the Supreme Court concluded that the allegations regarding the frustration of the PAO confined the action to the recovery process rather than a broad arbitrary prosecution. Does this ruling set a precedent for judicial deference to specialized tribunals in complex financial legislation? The answer appears to be a resounding yes. The ruling delivers a powerful message: in complex financial cases governed by detailed special legislation like the PMLA, the constitutional courts will defer to the statutory appellate forums. JSW Steel was therefore directed to pursue its appeals before the Tribunal, thereby allowing the comprehensive statutory process to run its logical course. This judgment serves as a vital reminder to litigants—and a confirmation for the ED—that the PMLA’s in-built mechanism must be exhausted before seeking intervention from the highest court.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision to decline the quashing of PMLA proceedings against JSW Steel delivers a clear mandate on judicial restraint and the sanctity of statutory remedies. By steering the appellant toward the Appellate Tribunal under Section 26 PMLA, the Court has not merely disposed of a petition; it has reinforced the comprehensive, self-contained structure of the PMLA’s adjudicatory mechanism. The core issue of whether the ₹33.80 crore truly constitutes “proceeds of crime” under Section 2(1)(u), or whether the subsequent withdrawals constituted a wilful violation of the PAOs, is now firmly placed where the Parliament intended: within the domain of specialized financial appeal. This ruling is a potent reminder that in the face of complex legislation, especially one dealing with the ‘continuing offence’ of money laundering, superior courts will not easily interdict a process that has its own internal checks and balances, thereby preventing a parallel adjudication that could undermine the Tribunal’s authority.

The true future ramifications of this judgment will be felt in how corporations approach the initial stages of enforcement action. It firmly establishes that merely being cleared of the predicate offence does not grant automatic immunity from PMLA investigation if subsequent actions—such as the alleged dissipation of attached funds—are themselves framed as an offence under Section 3. Moving forward, critical questions will inevitably be posed to the Appellate Tribunal and, eventually, to the Supreme Court once more: Does the principle of exhaustion of statutory remedies invariably preclude constitutional courts from examining whether a PMLA complaint survives the quashing of the underlying scheduled offence? Furthermore, in technical matters, how will the Tribunal definitively characterize the nature of cash-credit accounts in the context of PMLA attachments, especially when juxtaposed against the legal definition of ‘property’? This judicial restraint, while upholding procedure, casts a long shadow, compelling entities under ED scrutiny to diligently fight their battles within the Act’s framework, lest they be viewed as having an ‘apprehension’ rather than a clear case of ‘patent illegality.’

Citations

- Jsw Steel Limited Etc.Versus Deputy Director, Directorate Of Enforcement Etc.Criminal Appeal Nos.4183 4184 OF 2025

- Directorate of Enforcement

- Prevention of Money Laundering Act,2002

- Central Bureau of Investigation

- Vijay Madanlal Choudhary and Others v. Union of India and Others(2023) 12 SCC 1

- Provisional Attachment Orders

- Skytech Rolling Mill Pvt. Ltd. v. Joint Commissioner of State Tax Nodal 1 Raigad Division2025:BHC-OS:8549-DB

- State of Maharashtra v. Tapas D. Neogy1960 SCC OnLine SC 21

- Union of India and Another v. Guwahati Carbon Limited (2012) 11 SCC 651

- R.P. Kapur v. State of Punjab1960 SCC OnLine SC 21

- State of Haryana and Others v. Bhajan Lal and Others. 1992 Supp (1) SCC 335

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit