Introduction

Is a single challenge permissible when a party successfully weaves together multiple distinct legal disputes into one consolidated proceeding, culminating in a single, composite arbitral award? This precise question lay at the heart of a recent, significant ruling by the Calcutta High Court in Damodar Valley Corporation Vs. AKA Logistics Private Limited1. A bench led by Justice Shampa Sarkar unequivocally held that a single petition under Section 34 of the Arbitration Act2, is maintainable to challenge a composite arbitral award that disposes of multiple underlying references.

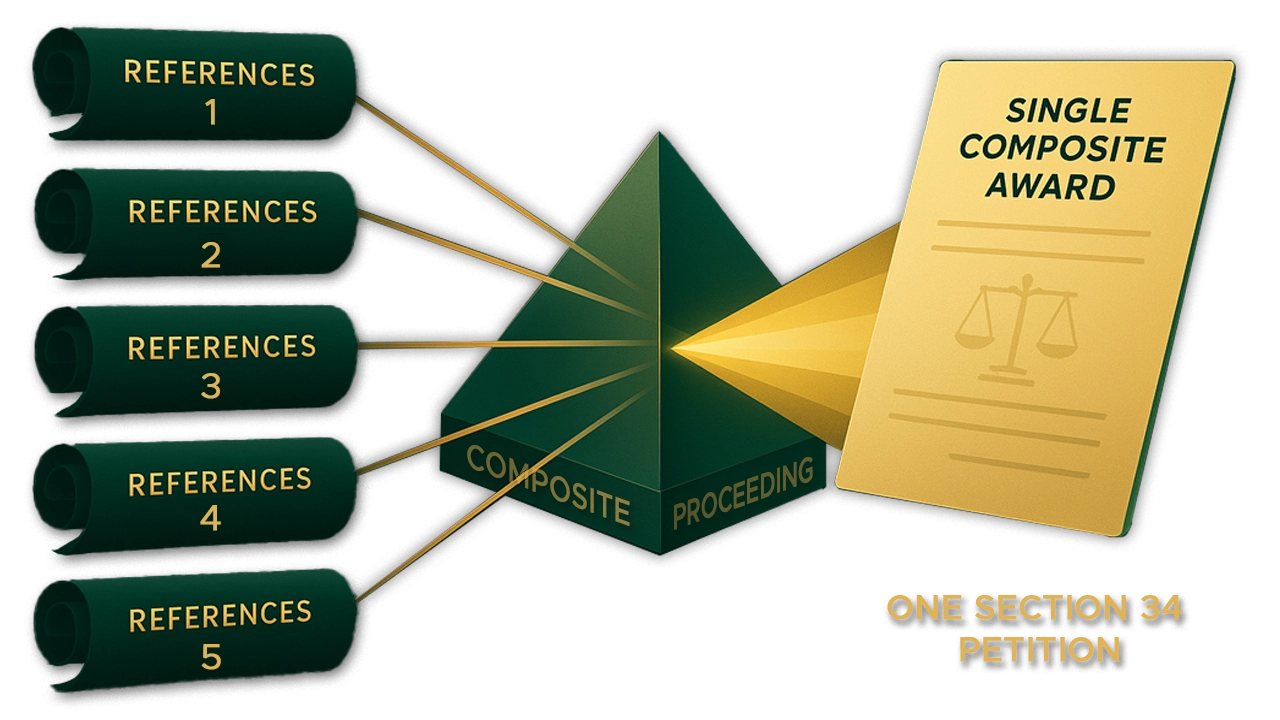

This judgment arose from a dispute between Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC) and AKA Logistics, involving five separate contracts for coal handling, where, despite five distinct initial references, the parties consented to an analogous hearing resulting in a single award. The core legal issue was whether DVC’s single Section 34 petition challenging this unified award was valid, or if AKA Logistics’ objection, insisting on five separate petitions, should prevail. This article will delve into the underlying legal principles and the rationale that informed the High Court’s decisive pronouncement on this critical procedural aspect of arbitration law.

The court did not hesitate to hold that where the learned arbitrator and the parties themselves understood the proceeding to be one composite proceeding—a fact evidenced by the parties’ consent to an analogous hearing—and the arbitrator proceeded to pass a composite award, a single challenge is entirely permissible. This position stems from the fundamental principle that the award is to be treated as one adjudication, an indivisible unit of resolution, even though it arose out of five distinct original references.

The court rejected the vehement argument that because five references culminated in distinct findings and claims, five separate challenge petitions were mandated. It clarified that the determining factor is not the number of original references, but the form and the nature of the award made and published and the procedure followed during the proceedings. The fact that the arbitrator circulated five copies of the self-same award, or corrected the award based on a single application and single order, was held not to change its fundamental nature from a composite to five separate awards. The award, when read as a whole, indicated that it was one adjudication of the claims arising from all five references, which were disposed of together. To insist on multiple petitions would be a hypertechnical approach that would clearly defeat the objective of speedy and efficacious adjudication that the 1996 Act was promulgated to ensure, leading only to delay and multiplicity.

This judicial clarity finds strong support in prior Supreme Court authority. In ONGC Vs. Saw Pipes Pvt. Ltd3., the Hon’ble Apex Court had already observed that in an application for setting aside an award, the arbitral award was the subject matter of challenge in its entirety and not claim wise. Furthermore, the Supreme Court, in State of Orissa Vs. Damodar Das4, held that when several disputes were decided by a single award, it nonetheless retained the character of a single award for the purpose of a proceeding for setting aside the award. The court here noted that even though the arbitrator separately quantified the monetary component for each reference, the ultimate intention was not to treat the proceedings as separate, which was clinched by the fact that interest was granted on the total sum awarded upon consolidation of all claims. This legal stance, permitting consolidated challenge, was also previously clarified by the Delhi High Court in Union of India Vs. C.C. Sharma, which confirmed that the maintainability of a single application under Section 34 could not be doubted where multiple claims or references were disposed of by a common award. While permitting the single petition, the court did impose a critical procedural condition: the court fee must be calculated in accordance with the claim awarded against each reference, and any deficit fee must be paid by the petitioner (DVC).

The reasoning for treating the composite arbitral award as a single unit is buttressed by its sharp distinction from a civil court decree. The court emphasized that the arbitral award cannot be equated with a decree of a civil suit. A decree, which is the formal operative instrument that conclusively determines the rights, is expressly appealable under Section 96 of the CPC, and each decree is a distinct adjudication of rights and liabilities. Even if multiple decrees are drawn up in suits disposed of analogously, each decree must be challenged by a separate appeal.

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, however, does not contemplate drawing up a decree. Section 34 provides that recourse to a court against ‘an’ arbitral award may be made only by ‘an’ application for setting aside such award. Thus, the requirement of the CPC that each decree be appealable separately cannot be imported into a challenge of a composite award, which, even if composite, remains one unit of adjudication and is challenged as a whole.

Finally, the court addressed the prayer for an unconditional stay of the money award under Section 36(2), a post-amendment power governed by the principles of Order 41 Rule 5 of the CPC. Since the 2015 amendment, the mere filing of a Section 34 petition no longer automatically stays the award. The court held that an unconditional stay is a very narrow exception brought in by the second proviso to Section 36(3) (the 2021 amendment) and is reserved only for a special case where the making of the award was, prima facie, found to have been induced by fraud or corruption.

The court found that the award debtor’s challenge was on the merits and there were no credible materials to show that the award was a product of fraud (deliberate deception, suppression, or collusion) or corruption (influence by illegal gratification or abuse of power). Citing the Delhi High Court’s ruling in NTPC Limited vs. Voith Hydro Joint Venture5, which affirmed that the threshold to establish prima facie fraud or corruption is very high, the court denied the unconditional stay, instead granting a conditional stay upon the deposit of a substantial amount, thus securing the sum awarded.

Conclusion

The High Court’s definitive ruling on the maintainability of a single challenge to a composite arbitral award marks a significant victory for the pragmatic application of arbitration law, underscoring the priority of speedy and efficacious adjudication over procedural formalism. By treating the composite award as one indivisible adjudication—a sharp contrast to the appeal requirements for multiple decrees under the CPC—the court effectively harmonized the procedure under Section 34 with the actual conduct of the consolidated arbitral proceedings. This decision, backed by the Supreme Court’s authority in ONGC Vs. Saw Pipes Pvt. Ltd. and State of Orissa Vs. Damodar Das, confirms that the substance and unified form of the final award dictate the challenge mechanism, not merely the historical number of initial references. Furthermore, the court’s rigorous application of the conditional stay provisions under the second proviso to Section 36(3), which demands specific proof of fraud or corruption, reinforces the finality of the award and prevents the automatic frustration of arbitral success through simple litigation on merits.

The future ramifications of this judgment are profound, primarily promoting greater efficiency and predictability in complex, multi-reference arbitrations, particularly those involving large infrastructure or commercial projects where disputes often stem from several related contracts. By endorsing the single-challenge approach, the ruling streamlines the post-award process, saving both judicial time and significant cost burdens for the parties, who are now spared the expense and complexity of filing numerous identical challenge petitions. It reinforces the autonomy of the arbitral process where, if parties consent to consolidation, the resulting award’s character remains unified. However, this ruling also opens the door to intriguing legal questions: If a court finds one specific claim—out of five consolidated references in the composite award—to be patently illegal (a ground for setting aside under the Act), will the court feel compelled to treat the award as truly “indivisible,” or will it attempt a surgical setting aside of only the problematic portion? Can this single challenge lead to a partial setting aside that affects the shared components, such as the unified interest awarded across all references?

Ultimately, the judgment sends a clear, pro-arbitration message that procedural objections intended only to delay execution and multiply litigation will be rejected. By prioritizing the unified character of the final composite award, the Calcutta High Court has reinforced the finality and enforceability of arbitral awards. It signals that once parties and their arbitrator choose to consolidate references into a single adjudication, the legal consequences, both for the challenge under Section 34 and for the application of stay under Section 36, must follow that path of procedural unity, ensuring justice remains cost-effective and efficient.

Citations

- Damodar Valley Corporation Vs. AKA Logistics Private Limited AP-COM -166 of 2025

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

- ONGC VS. Saw Pipes Pvt, Ltd., reported in AIR 2003SC 2629

- State of Orissa Vs. Damodar Das,reported in AIR 1996 SC 942

- NTPC Limited vs. Voith Hydro Joint Venture, decided in OMP (COMM) 16/2017 & I.A No. 528/2017

Expositor(s): Adv. Anuja Pandit