Introduction

The hum of a petrol pump, the clatter of a contractor’s vehicles – a seemingly mundane transaction, yet one that unexpectedly ignited a legal blaze, casting a spotlight on the meticulous demands of financial law. Imagine a scenario where a significant debt, acknowledged by a cheque, spirals into a legal quagmire not over the debt itself, but over who exactly has the right to claim it. This is precisely the fascinating legal conundrum that recently landed before the Himachal Pradesh High Court in Shirgul Filling Station Versus Kamal Sharma1 unraveling the intricate threads of proprietorship and authorization within the ambit of the NI Act2.

At the heart of this dispute lay a cheque for INR 5,00,000/-, allegedly issued to settle a fuel bill by a government contractor to Shirgul Filling Station. When the cheque bounced, Ankur Aggarwal, identifying himself as the Manager of the filling station, swiftly initiated legal proceedings. But here’s where the plot thickened: the cheque was in the name of the filling station, and Mr. Aggarwal’s claim to pursue the matter hinged on an authority letter obtained after the legal notice was dispatched and the complaint already filed. Could such a post-facto authorization legitimize his standing as the “payee” or “holder in due course” under Section 138 of the NI Act? The Himachal Pradesh High Court, in a ruling that resonates with clarity and precision, firmly declared that it could not. This case, a compelling narrative of legal exactitude versus perceived practicalities, compels us to dissect the nuances of a judgment that profoundly impacts how sole proprietorships navigate the legal landscape of dishonoured cheques. Let’s delve deeper into the court’s discerning analysis and unearth the critical takeaways for businesses and legal practitioners alike.

The aggrieved complainant, however, was not one to concede defeat. Ankur Aggarwal, through his counsel, vehemently appealed the Trial Court decision, arguing that the court had erred in deeming him unauthorized. His primary contention? The authority letter, even if issued post-complaint, effectively rectified any initial defect, a permissible course of action during ongoing proceedings. He emphasized the unrebutted evidence of fuel purchases, the accused’s failure to present a defense, and the satisfaction of all Section 138 ingredients.

“A mere technicality shouldn’t derail justice,” argued the appellant’s counsel, presenting a compelling case built on precedents like M/s Mohan Meakin Limited vs. M/s Spirit and Beverages L-1, MMTC Ltd. and Anr. Vs. Medchl Chemicals and Pharma Pvt. Ltd. and Anr3., and Haryana State Cooperative Supply and Marketing Federation Limited vs. Jayam Textiles and Anr4. These judgments, the appellant asserted, supported the principle that defects in authorization for a juristic person could be cured.

But the counsel for the accused, Kamal Sharma, stood firm, defending the Trial Court’s “reasonable view.” He underscored the absence of a proper power of attorney and, crucially, the lack of evidence proving Shivani Gupta’s proprietorship of Shirgul Filling Station. Citing Milind Shripad Chandurkar v. Kalim M. Khan5, A.C. Narayana versus State of Maharashtra6, and Janki Vashdeo Bhojwani v. Indusind Bank Ltd7., the accused’s counsel implored the High Court not to interfere with a well-reasoned acquittal.

Now, as the arguments echoed in the hallowed halls of justice, the High Court, mindful of its appellate mandate, turned to the well-established principles governing appeals against acquittal. As elucidated in Surendra Singh v. State of Uttarakhand8, and further reinforced by Babu Sahebagouda Rudragoudar v. State of Karnataka9 and Rajesh Prasad v. State of Bihar10, interference is warranted only if the acquittal is “patently perverse,” based on “misreading of evidence,” or if “no reasonable person could have recorded the acquittal.” The court’s role, as emphasized in Chandrappa v. State of Karnataka11 and H.D. Sundara v. State of Karnataka12, is to determine if the Trial Court’s view was a possible view, not merely if another view was also conceivable. The “double presumption of innocence” for the accused, particularly after an acquittal, loomed large.

With these guiding principles firmly in mind, the High Court meticulously scrutinized the evidence. Ankur Aggarwal himself, in his cross-examination, had conceded that Shivani Gupta owned Shirgul Filling Station and that he lacked documentation to prove his managerial position or authorization at the time of filing. The “special power of attorney” he volunteered to possess remained unverified. Furthermore, the statement of account) conspicuously omitted Shivani Gupta’s name.

This critical absence of proof of proprietorship became the linchpin of the High Court decision. Recalling the Supreme Court pronouncement in Milind Shripad , where a complainant’s mere statement of proprietorship, unsupported by documentary evidence, was deemed insufficient, the Himachal Pradesh High Court found a striking parallel. In Milind Shripad Chandurkar, despite the accused raising the issue at every stage, the complainant failed to produce any nexus with the proprietorship firm, even for a business of significant turnover. The Supreme Court unequivocally stated that without establishing such a connection, the complainant could not be considered a “payee” or “holder in due course.” This precedent was steadfastly followed by the Himachal Pradesh High Court in S.P. Saklani v. Ravinder Singh Thakur13 and Ram Chand v. Rafee Mohammad14, both reinforcing that a bare assertion of proprietorship, without cogent documentary proof, is simply not enough. The law, it seems, demands more than just a claim; it demands proof, particularly when it comes to who legally holds the right to initiate such a serious complaint.

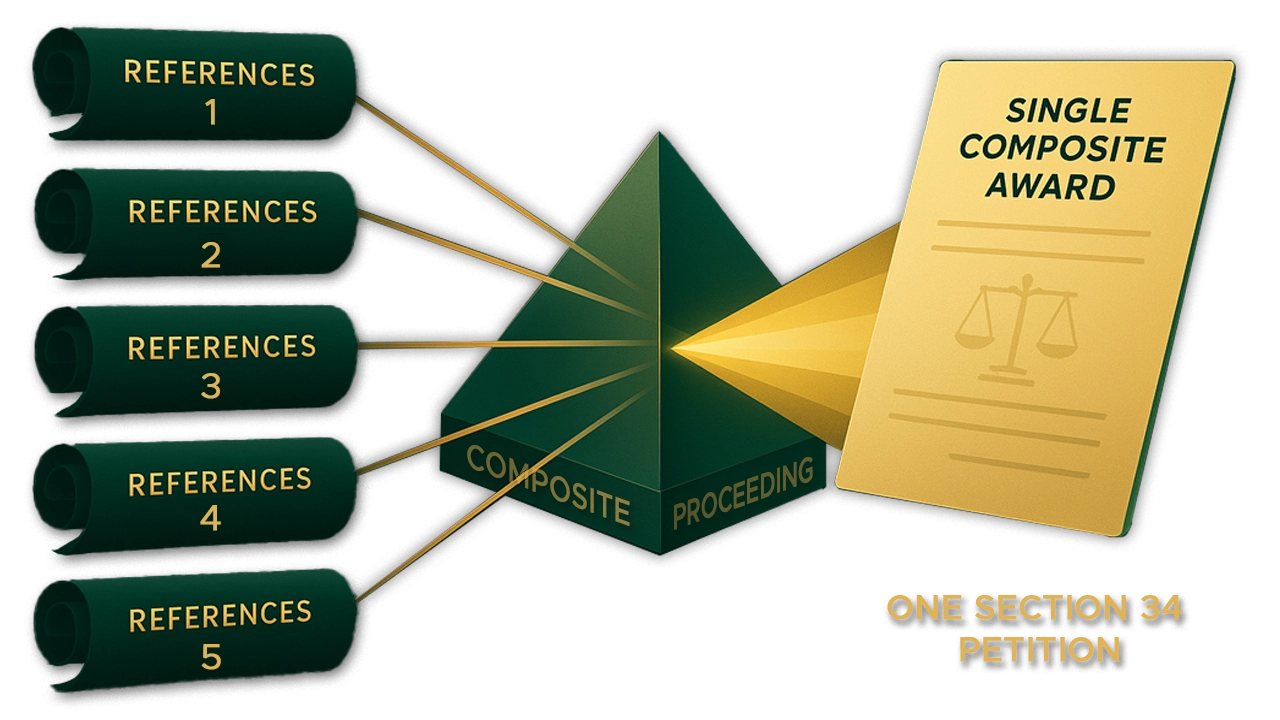

Crucially, the High Court distinguished the present case from those cited by the appellant, such as Mohan Meakin and MMTC Ltd., noting that those judgments dealt with complaints filed by companies – juristic persons that, by their very nature, require a natural person to represent them, and where defects in authorization could indeed be rectified. However, a proprietorship concern, the court emphasized, is considered equivalent to a natural person. Therefore, the strict requirements for the complainant to be the “payee” or “holder in due course” directly apply.

In the end, the High Court concluded that the Trial Court had taken a “reasonable view,” supported by clear judicial precedents. With no satisfactory evidence to establish Shivani Gupta as the owner of Shirgul Filling Station, and consequently, Ankur Aggarwal’s lack of standing as a “payee,” the appeal was dismissed. The legal tale of the dishonoured cheque thus concluded, reaffirming the paramount importance of establishing proper legal standing and proprietorship in such disputes.

Conclusion

The Himachal Pradesh High Court’s judgment serves as a resounding clarification of the stringent requirements for initiating proceedings under Section 138 of the NI Act, particularly concerning sole proprietorships. By unequivocally stating that a complainant must establish themselves as the legitimate “payee” or “holder in due course” through concrete proof of proprietorship, and that belated authority letters are insufficient, the Court has drawn a clear line in the sand. This decision reinforces the principle that procedural correctness and substantive legal standing are not mere technicalities but foundational pillars for the administration of justice in financial disputes. The emphasis on documentary evidence over mere assertions, even in cases where the underlying debt may be apparent, underscores the judiciary’s commitment to preventing frivolous or improperly instituted complaints.

Looking ahead, this ruling carries significant implications for business practices, especially for sole proprietorships. It mandates a proactive approach to maintaining impeccable records of ownership and authorization. Proprietors must ensure that any individual handling financial transactions or legal matters on their behalf possesses a robust and legally valid power of attorney or similar instrument prior to any dispute arising. The notion that defects can be cured at a later stage, while applicable in certain corporate contexts, has been definitively curtailed for proprietorships in this specific scenario. This judgment ultimately acts as a vital reminder to sole proprietors and anyone dealing with them: in the complex dance of commercial transactions, legal authority and accurate documentation are as crucial as the transaction itself. The time to establish your legal standing is not when a cheque bounces, but long before the first fuel tank is filled or the first debt is incurred.

This judgment naturally gives rise to several pertinent questions for the future. How will courts interpret “payee” or “holder in due course” for nascent or informal proprietorships that may not have extensive formal documentation initially, and will the standard of proof vary based on business size? What specific date or event will be considered the absolute cut-off for “prior” authorization, and will this ruling disproportionately affect smaller sole proprietorships lacking sophisticated legal or accounting infrastructure? Finally, what specific types of documentary evidence will be considered irrefutable proof of proprietorship in future cases, moving beyond typical tax records?

Citations

- Shirgul Filling Station Versus Kamal Sharma Cr. Appeal No.262 of 2010

- Negotiable Instrument Act, 1881

- MMTC Ltd. and Anr. Vs. Medchl Chemicals and Pharma Pvt. Ltd. and Anr., 2002 (1) SCC 234

- Haryana State Cooperative Supply and Marketing Federation Limited vs. Jayam Textiles and Anr.2014 (4) SCC 704

- Milind Shripad Chandurkar v. Kalim M. Khan, (2011) 4 SCC 275,

- A.C. Narayana versus State of Maharashtra,2015 (12) SCC 203

- Janki Vashdeo Bhojwani v. Indusind Bank Ltd.(2005) 2 SCC 217

- Surendra Singh v. State of Uttarakhand2025 SCC OnLine SC 176

- Babu Sahebagouda Rudragoudar v. State of Karnataka 2024 SCC OnLine SC 4035

- Rajesh Prasad v. State of Bihar (2022) 3 SCC 471

- Chandrappa v. State of Karnataka(2007) 4 SCC 41

- H.D. Sundara v. State of Karnataka(2023) 9 SCC 581

- S.P. Saklani v. Ravinder Singh Thakur Saklani v. Ravinder Singh Thakur, 2012 SCC OnLine HP 771

- Mohan Meakin Limited vs. M/s Spirit and Beverages L-1 passed in Cr. Appeal No. 592 of 2017

Expositor(S): Adv. Anuja Pandit