Introduction

India’s intellectual property landscape, particularly regarding Geographical Indications (GIs), is a vibrant domain designed to safeguard the unique identity and traditional craftsmanship associated with specific regions. The GI Act1 and its accompanying Rules of 2002 serve as the bedrock of this framework. They empower producers to protect goods whose distinctive qualities are intrinsically linked to their geographical origin, be it through natural factors, human skill, or cultural heritage. The registration of a GI grants exclusive rights to its authorized users, allowing them to prevent others from misleadingly using the indication for products not originating from that specific area.

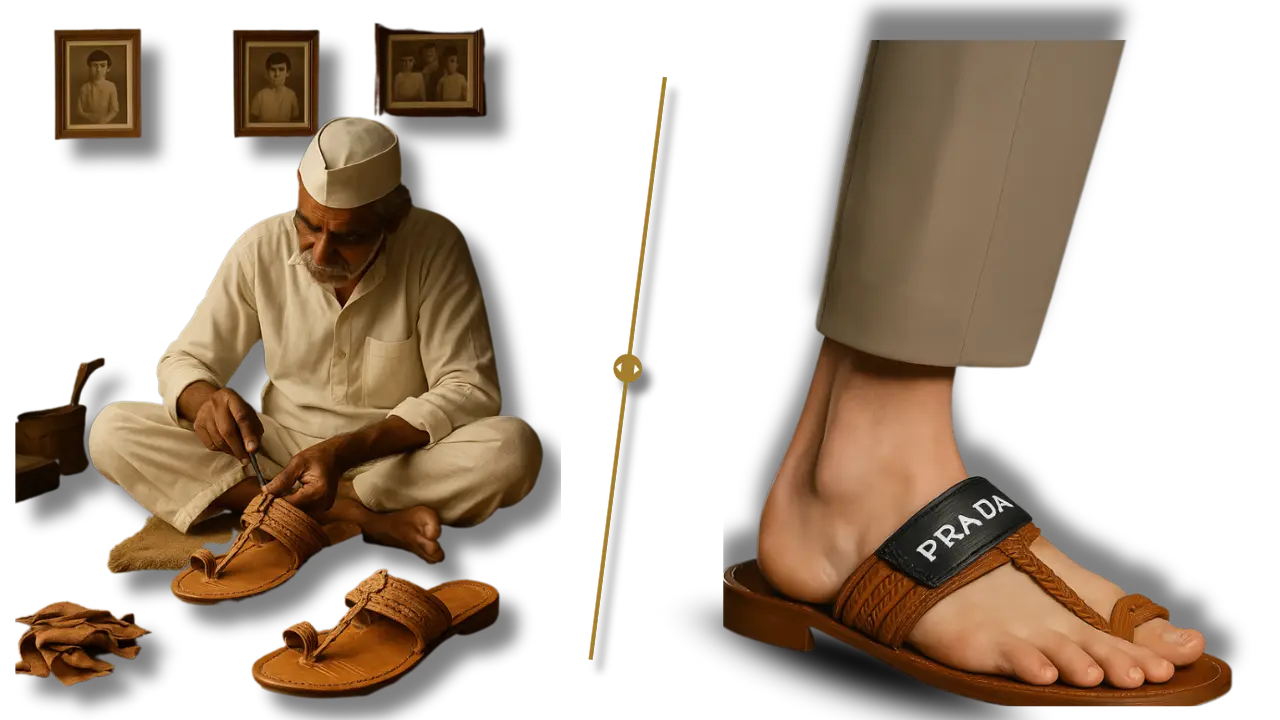

This framework recently found itself under the spotlight following the unveiling of Prada’s Spring/Summer 2026 collection. The luxury fashion house presented sandals that bore a striking resemblance to India’s humble Kolhapuri Chappals, a footwear deeply embedded in Indian culture and a registered GI product. This visual similarity sparked a significant digital outcry in India, with accusations of cultural appropriation and potential GI infringement against Prada. The incident has naturally led to a crucial question: does an actionable claim for GI infringement against Prada truly stand?

The Kolhapuri Chappal: A Symbol of Heritage

The Kolhapuri Chappal, traditionally handcrafted with its unique toe-loop design, is much more than just footwear; it is a symbol of artisanal heritage and a source of livelihood for countless craftspeople. Produced in specific districts of Maharashtra and Karnataka, this traditional craft received GI registration in 2018, with LIDCOM2 and LIDKAR3 named as the registered proprietors under the GI Act. Today, over 900 authorized users, employing traditional techniques and vegetable-dyed leather, contribute to its production. The GI tag was intended to shield this traditional product from imitation and ensure the economic welfare of its artisans.

The Prada Collection: An Acknowledged Inspiration, But Is It Infringement?

Prada’s collection certainly drew inspiration from traditional Indian footwear, a fact the brand has now acknowledged. However, the core legal question revolves around whether this inspiration translates into an actionable GI infringement under Indian law.

To understand this, one must delve into Section 22 of the GI Act, which outlines what constitutes infringement. An unauthorized user commits infringement if they use the GI:

- In the designation or presentation of goods in a manner that misleads consumers about the true geographical origin of those goods.

- In a way that constitutes an act of unfair competition, including passing off.

Let’s dissect this with respect to the Prada case

Firstly, Prada has not used the “Kolhapuri Chappal” GI in the naming or marketing of its 2026 Summer Collection. The brand has explicitly stated that its sandals were “leather sandals” inspired by Indian footwear, rather than being labeled as “Kolhapuri Chappals.” This is a crucial distinction. For instance, in the past, the Scotch Whisky Association successfully took action against Indian distilleries for using “Scotch” on their labels for whiskies not originating from Scotland. The Delhi High Court eventually prohibited these companies from using terms like “Scotch” or “Scotch Whisky” for their Indian-produced spirits, highlighting the importance of preventing misleading claims of origin.

Secondly, Prada has not infringed the exclusive right to use the GI granted to authorized users under Section 21(1)(b) of the GI Act. This section grants authorized users the exclusive right to use the GI in relation to the goods for which it is registered. For instance, a company like Korakari, which sells footwear branded as “Kolhapuri Chappals,” is not infringing because it is registered as an authorized user. If Korakari were to brand its footwear as “Kolhapuri Chappals” without being an authorized user, that would unequivocally be an infringement. Prada, however, is not claiming its collection includes “Kolhapuri Chappals”; it is presenting a design inspired by them.

Finally, the aspect of “passing off” under Section 22(b) warrants examination. Passing off, as interpreted in GI law, mirrors its meaning in trademark law. In cases like Tea Board, India v ITC Ltd4. (2011), the Calcutta High Court deliberated on this. While there is an undeniable visual similarity between Prada’s sandals and traditional Kolhapuri Chappals, Prada has not branded its footwear with the “Kolhapuri Chappal” name or any deceptively similar appellation. The discerning consumer base for high-end luxury goods and the mode of purchase for Prada’s products are significantly different from those for traditional Kolhapuri Chappals, which are often sold at a much lower price point in local markets. Therefore, the likelihood of confusion among consumers regarding the origin of Prada’s sandals as actual Kolhapuri Chappals seems remote, making a claim for unfair competition or passing off challenging.

Jurisdictional Considerations: A Non-Issue

Should the proprietors of the Kolhapuri Chappal GI decide to pursue legal action, jurisdictional issues would likely not pose a significant hurdle. Section 66(1)(a) of the GI Act specifies that a suit for infringement can be filed in a district court having jurisdiction. Furthermore, Sub-section (2) allows plaintiffs to file such a suit in a district court within whose local limits they actually and voluntarily reside, carry out business, or work for gain. This means that LIDKAR and LIDCOM, being situated in Bengaluru and Mumbai respectively, would be able to file a suit in courts within their jurisdictions.

Implications for GI and IP Policy in India

While the Prada instance may not constitute a direct infringement under the current GI Act, it brings to the fore critical discussions about the evolving landscape of intellectual property and cultural appropriation. GI tags are fundamentally intended to protect the authenticity of regional products and foster equitable socio-economic development for their producers. The challenge, as observed with Kolhapuri Chappals facing competition from imitations, lies in empowering traditional artisans to combat revenue losses and market risks.

The Prada controversy, though legally distinct from direct infringement, highlights a broader concern: how does GI law address instances where the design of a GI-protected product is appropriated without using the protected name? While current Indian GI law primarily focuses on the use of the name or designation that misleads consumers about geographical origin, this incident prompts a re-evaluation of whether the distinctive visual elements of GI-tagged products, particularly those deeply embedded in cultural heritage, should also receive enhanced protection against unauthorized commercial replication, even without explicit name usage.

This development serves as a vital reminder for India’s GI framework to continually adapt and strengthen its mechanisms, ensuring that the spirit of GI protection – preserving heritage and empowering local communities – is upheld in an increasingly interconnected and globally inspired fashion world. The debate sparked by the Prada-Kolhapuri situation is not just about a single fashion collection; it’s a call to reflect on the nuances of intellectual property in a world where inspiration and imitation often walk a fine line.

Conclusion

The Prada-Kolhapuri Chappal episode, while seemingly a straightforward case of design inspiration, has undeniably served as a fascinating litmus test for India’s Geographical Indications framework. It underscores the robust yet specific nature of GI protection in preventing misleading claims of origin, as evidenced by Prada’s careful avoidance of the GI name. This clarifies that merely drawing aesthetic inspiration, without falsely associating a product with the GI’s geographical origin, does not fall under the purview of direct infringement as currently defined.

However, does this mean that our existing legal provisions are entirely sufficient in an era where cultural designs are increasingly becoming global commodities? The controversy compels us to ponder a critical shortcoming: while the GI Act diligently guards against the misuse of a name, it offers limited recourse against the appropriation of distinctive design elements themselves, especially when they are deeply intertwined with a community’s traditional knowledge and cultural identity. For artisans to truly benefit from GI tags and safeguard their heritage, is it not imperative for the legal framework to evolve, perhaps by exploring enhanced protection for the unique visual characteristics that make products like Kolhapuri Chappals instantly recognizable, regardless of the name used?

Looking ahead, the implications of such incidents are profound. This could catalyze a vital dialogue on strengthening intellectual property policies to better address cultural appropriation, potentially through closer integration with design patents or sui generis rights for traditional cultural expressions. Furthermore, it highlights the need for increased awareness among traditional artisans about their intellectual property rights and avenues for collective action. Ultimately, securing a product’s GI tag is merely the first step; its true potential is realized when it translates into tangible economic benefits for the originating communities and protects their centuries-old craftsmanship from being merely “inspired” away without appropriate recognition or reciprocity.

Citations

- The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999

- Sant Rohidas Leather Industries & Charmakar Development Corporation

- Dr. Babu Jagjivan Ram Leather Industries Development Corporation

- Tea Board, India v ITC Ltd.GA No. 3137 of 2010

Expositor(S): Anuja Pandit