Introduction

The very architecture of justice is built upon the premise of scrutiny. When an administrative or quasi-judicial body decides on a matter as vital as proprietary rights for instance, the registration of a trademark, does the aggrieved party have an unassailable right to multiple tiers of judicial review, an assurance of appellate grace? Or can a subsequent statutory amendment, a single legislative stroke, extinguish an otherwise vested right to an intra-court appeal? This intricate question lies at the heart of the constant judicial endeavour to reconcile the specific provisions of special legislation with the sweeping procedural mandate of general law, a conflict recently crystallised by the Calcutta High Court in the landmark judgment of Glorious Investment Limited vs. Dunlop International Limited & Anr1.

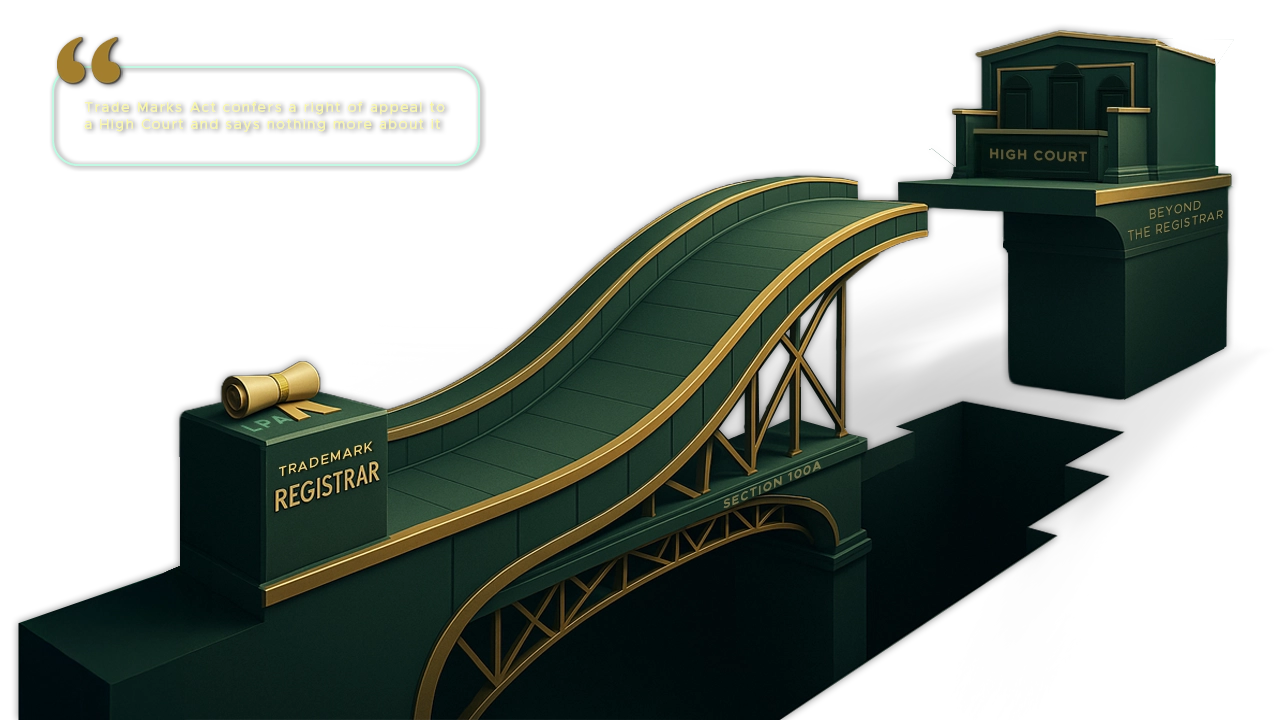

The crux of the matter revolves around the maintainability of a Letters Patent Appeal (LPA) against the order of a Single Judge of the High Court. The appeal before the Single Judge itself originated as a challenge under Section 91 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, against a decision rendered by the Registrar of Trademarks. The objection raised is potent: the appeal is, in effect, a second appeal, and by virtue of Section 100A of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), 1908, no further appeal lies from the judgment of a Single Judge of a High Court that has heard and decided an appeal from an original or appellate decree or order.

Historically, the law seemed settled. The Supreme Court, in the seminal 1953 case of National Sewing Thread Co. Ltd. vs. James Chadwick & Bros. Ltd2., provided a clear pathway. The principle established was that when a special statute, like the Trade Marks Act, confers a right of appeal to a High Court and “says nothing more about it,” the appeal must be regulated by the practice and procedure of that Court. Consequently, when a Single Judge exercised that jurisdiction, their judgment became subject to a further appeal under the Letters Patent of the High Court. The rule was one of general application: once a legal right is in dispute and the ordinary courts are seized of it, the courts are governed by their ordinary rules of procedure, and an appeal lies if authorised by those rules. This authoritative dictum meant that absent any express bar in the special statute, the right to an LPA was preserved.

However, the subsequent insertion of Section 100A into the CPC, effective from 2002, introduced a significant hurdle. The question quickly emerged: does this general bar extend to orders passed under special enactments, particularly when the initial authority is not a civil court? This is where the concept of the authority having the “trappings of a court” becomes the interlinking legal concept. The Supreme Court in Kamal Kumar Dutta & Anr. vs. Ruby General Hospital Limited & Ors. (2006)3, while dealing with an appeal under Section 10F of the Companies Act, 1956, found that although the Company Law Board (CLB) was not a court, it exercised quasi-judicial power as an original authority and possessed all the essential trappings of a court. The CLB was vested with powers under the CPC, like enforcing witness attendance, compelling document production, and its orders were enforceable like a Civil Court decree. Since the appeal from the CLB to the Single Judge was from an original order of an authority having the trappings of a court, the Supreme Court held that Section 100A unequivocally took away the power of the High Court to entertain a further Letters Patent Appeal.

Applying this crucial rationale, the Registrar of Trademarks must also be examined, as the Calcutta High Court did in the Glorious Investment case. The Trade Marks Act, 1999, itself bestows the Registrar with essential civil court powers for the purpose of receiving evidence, administering oaths, enforcing witness attendance, and compelling discovery and production of documents under Section 127. Furthermore, the Registrar’s decision to grant or reject a trademark registration directly impacts and determines the legal rights and liabilities of the parties, an indispensable characteristic of a judicial function. Therefore, by adopting the “trappings of a court” test, the Registrar’s function, like that of the erstwhile CLB, can be deemed to possess these essential qualities. This conclusion effectively extends the prohibition contained in Section 100A of the CPC to appeals filed under Section 91 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

This interpretation is further strengthened by examining the surrounding legislative intent and the interlinking predecessor statute. The predecessor legislation, the Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958, contained an express provision in Section 109(5) which stated that where an appeal was heard by a Single Judge, “a further appeal shall lie to a Bench of the High Court”. Tellingly, the successor Act of 1999, while shifting the appellate forum from the IPAB to the High Court, deliberately omitted this explicit provision for a second appeal. The legislature’s clear omission of a right of further appeal, which was explicitly present in the earlier Act, amounts to a tacit implication that such an appeal was not intended.

Conclusion

The shadow cast by Section 100A of the CPC proves too formidable for the Letters Patent to penetrate in this context. Despite the general rule favouring the survival of an intra-court appeal where a special statute is silent, the Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court in Glorious Investment Limited vs. Dunlop International Limited & Anr. found the combination of two factors to act as a conclusive bar: first, the overriding force of Section 100A, which applies because the Registrar of Trademarks exercises a function that possesses the “trappings of a court”; and second, the implied legislative intent evident from the deliberate removal of the second appeal provision from the 1999 Act, a provision that was present in the 1958 Act. The vested right of appeal, while foundational, is thus conclusively taken away by the subsequent express and implied mandate of the law. The flow of litigation in trademark appeals under Section 91 stops at the Single Judge’s door, yielding to the will of the Parliament.

Citations

- Glorious Investment Limited vs. Dunlop International Limited & Anr. IA No: GA – COM 1 of 2025

- National Sewing Thread Co. Ltd. vs. James Chadwick & Bros. Ltd. PTC (Suppl) (1) 475 (SC)

- Kamal Kumar Dutta & Anr. vs. Ruby General Hospital Limited & Ors. 2006)7 SCC 613

Expositor(s): Adv. Archana Shukla